1979

A change of name, a fortuitous wedding gig and the first appearance in both the charts and the Top of the Pops studios.

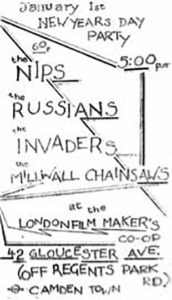

JANUARY 1: The London Film-Makers Co-op

Read more

The Invaders perform at a New Year’s Day party supporting The Millwall Chainsaws and headlined by The Nips, Shane McGowan’s punk band. Due to the frosty weather only three people turn up, who immediately leave once The Invaders have finished. The set now includes seven of their own songs and Lee takes the vocals for Razor Blade Alley, while Suggs and Chris swap roles for Memories (later the B-side of Grey Day). The encore sees them play Suggs’ first composition, I Lost My Head. A change of name is now a priority as another band called The Invaders have been offered a contract by Sham 69 singer Jimmy Pursey.

setlist

Sunshine Voice / Roadette Song / Rich Girls / My Girl / Tears of A Clown / Razor Blade Alley / You Said / Mistakes / Madness / Memories / Shoparound / Believe Me / Swan Lake / ENCORE: I Lost My Head .

SUGGS: Those early days were the best but also some of the worst, like when you’re playing in pubs to four people and having bottles thrown at you and there’s more light on the pool table than on the stage. We had no musical talent or anything. The only reason people would come to see us is because we’d go mad. And that was the idea – if we could do it, anyone could. We just felt that everyone should be themselves and not feel embarrassed about doing things out of the ordinary, like dancing or going mad.

CHRIS: Without wishing to seem big-headed, we knew we were different to any other group. Our line-up of instruments was quite unusual compared to most bands at that time, and we had a lot of songs.

CARL: We also had an inner power and jollity that just seemed to permeate into the crowds around us.

SUGGS: You get some people embarrassed about what they did in the past or they way they looked, but for some reason or another we started out in a pretty good place. And then we tried to keep in that place.

WOODY: It really was just mates getting together and going to play in pubs and clubs. We all went to the same parties and there seemed to be a different group every week. There were certain genres. You had the jazz funksters and the rockers – but there was no-one like The Invaders. We weren’t great or flashy musicians but we had a strength that came from unity. Our sound came from very simple playing, put together beautifully. There’d been generations of self-indulgent musicians wibbling away, but that’s not what we were about. We liked music you could dance to and we had fun, yet we also took it seriously without being self-indulgent.

SUGGS: We were young, we were extroverts and we just wanted to have fun. None of us had been in bands before and none of us had any idea what the music business was supposed to be. The great thing about that period was that we were still a gang, the road crew were all our pals, joining in on the backing vocals, and it was an ebullient time. We were the leaders of the little bit of North London we lived in and we all led colourful lives, which fed into the songs. I was the idiot savant – well, certainly an idiot – and was just happy to be there. They were all older than me and I just wanted to be in their gang or be cool. We were lucky. We were very happy to be making music and we were a big gang of mates that were just in our own little world. Fame and all that didn’t really seem of any consequence.

JANUARY 7: The Nashville Rooms, Kensington, London

Read more

Performing alongside The Immigrants and The Tribesmen, the band are late, so have to cut short their set. The Tribesmen’s manager shows interest and visits The Invaders backstage. His companion hears about their search for a new name and suggests The Iron Bars. He is ignored.

MIKE: We got the gig through the Tribesmen’s manager Steve Thomas who wanted to manage us. We got cut off halfway ’cause we came on too late.

SUGGS: We were kind of in the middle of everything as it evolved at the same time. We were getting our clothes from second-hand shops, like old tonic suits and pork pie hats and all that stuff. It was all very homemade and every scene had its own little epicentre – the whole thing was a fantastic kaleidoscope.

WOODY: Immigration shaped a lot of our musical landscape. Any ethnic influx that comes into the country obviously changes it, and London was just a brilliant melting pot of musical influences. The stuff that the Asians did, and the Jamaicans who came over in the ’50s – blimey, that was just an explosion. The influences they brought over were part of our heritage.

SUGGS: You had the second-generation of West Indian Brits coming through. You had Bob Marley on the Old Grey Whistle Test on TV. I remember going to the Roxy Club in Covent Garden, which was the punk club where Don Letts was the DJ, but there weren’t enough punk records to play so he would intersperse them with reggae tracks.

DON LETTS: There were literally no punk records to play, so I had to play something I liked, which was reggae: Big Youth, Prince Far I, Toots and the Maytals. Lucky for me, the audience liked it as well and wanted to hear more. So I guess it did turn a few people onto it.

SUGGS: You had The Clash doing a version of Police and Thieves and, all of a sudden, what had been completely polarised was bleeding at the edges and we were all starting to share a little bit, musically and stylistically. Certainly all those old Mowtown records had a huge influence on us. The connection – and you can only make this in hindsight, because when you’re a kid you’re just listening to records that get you going – was reading about The Skatalites and that whole ska thing; just a load of guys in a studio making four or five records a day with very little ego. I found it was the same with Motown and the Stax people, you know they were churning them out. I think for us that was a great inspiration the whole time after progressive rock, when everything seemed pretentious and long winded.

LEE: All the band other than Woody were brought up on a diet of Jamaican and Motown music. Mike was more interested in the ruder side of reggae, like Wet Dream and Wreck A Pum Pum. It was easy to play as well. As the interest in ska and reggae grew, we dropped stuff like Walk On By and Lover Please.

MIKE: We were listening to Bob Marley but reggae then [in the late 1970s] wasn’t as good, I didn’t think, as the older stuff. It was more about the producers. There were stars, of course, in Jamaica but it was more of a team thing.

SUGGS: We used to love Linton Kwesi Johnson and Bob Marley. But we found the righteous, Rastafarian stuff out of our league in terms of burning down Babylon. Punk bands were doing contemporary reggae but to me it didn’t seem as realistic as us just playing the songs we liked. No one else was doing ska, so we found our niche. The political message of Rastafari also wasn’t necessarily as clear for us as it was for punk rockers. I understood it but it didn’t resonate for us. [But] we loved the attitude of people who smoked dope and wouldn’t just sit around in a huddle in their bedroom, they’d be bowling down the street. You started hearing reggae in punk clubs and then you start thinking, ‘Yeah, I like this.’ So you start going back, investigating where these tunes come from. It was like, I had friends who were into rockabilly, and they started looking into bluegrass and hillbilly, trying to find other stuff that was more obscure and elitist.

CHRIS: The Jamaican thing was really important, but we had so many influences that get overlooked, like Pink Floyd and Genesis.

SUGGS: I thought ska was just reggae. I had to go and read all these Trojan liner notes so I could come back and say, ‘Oh yeah, Prince Buster this… Prince Buster that’.

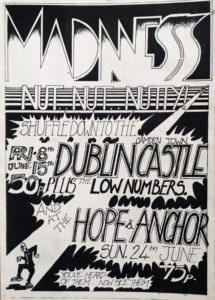

FEBRUARY 16: The Dublin Castle, Camden Town, London

Read more

A dream comes true as The Invaders make their Dublin Castle debut with ABC. The sold-out gig in front of 150 people serves as a taster of the Friday night stint they’ll enjoy later in the year.

SUGGS: The Dublin Castle is still my favourite pub, not least because it’s where we played some of our earliest concerts – you could call it the ancestral seat of Madness. I remember they had Irish bands on, because we went there to get one of our first concerts and had to pretend we played a bit of Irish music ourselves. There were about 10 or 12 Irish pubs in Camden Town that had a function room out the back, and it occurred to us, at the end of the punk thing, that you might get a gig if you just asked. So we would go round just knocking on doors and if there was nothing going on, the guv’nor might give you a gig. He didn’t really care as long as he sold a few pints.

WOODY: Punk still had the country wrapped up in this new, anarchistic and exciting ‘let’s change things’ vibe. It opened up the opportunity to walk into your local pub and say, ‘I fancy putting on a gig.’

BEDDERS: The owners weren’t bothered about the kind of music you played as long as you brought in a lot of people to drink. And we always told them, ‘Oh, we have lots of friends.’

HENRY CONLON (son of original landlord, Alo Conlon): Seven young men came in and said they were a jazz band and asked if they could get a gig.

SUGGS: Having trudged round just about every pub in Camden in search of a gig, it was with the echo of rejections still ringing in our ears that we entered The Dublin Castle with its red-and-cream exterior and hanging baskets. ‘What’s your act then, lads?’ enquired the genial Irish guv’nor.

BEDDERS: A school friend of mine had got a gig there playing some weird jazz/rock fusion, so he said, ‘Say you can play jazz and you’ll be fine.’ So me, Mike and Chris replied, ‘We play jazz, and a little bit of country and western.’

SUGGS: He took us through the Dublin’s red-lit, mock-Tudor bar to the back room, which was used for functions and the occasional bit of live Irish music. It was pretty damn impressive, especially the stage, which was made up of sheets of hardboard laid across stacks of beer crates. Up to this point, we’d really only played a few private parties and this room felt like the real deal. It looked like it could hold 150 people at a pinch, which felt like Wembley to us. ‘What do you think lads?’ asked Alo. ‘Yeah, it’s OK,’ we replied, trying to look nonchalant. We had, at last, landed on our feet.

BEDDERS: Alo asked when we could come along, duly gave us a night, and everything went from there.

HENRY CONLON: Dad had thought, ‘Oh, jazz, that’s nice and respectable.’ So he was not a little surprised the following Friday when a bunch of skinheads showed up. He thought, ‘What am I doing?’

LEE: It was 50p entry and we got paid in cash; all of £4.50 each.

SUGGS: When seven skinny teenagers in funny suits started leaping about playing Jamaican ska, the Irish regulars were somewhat bemused.

BEDDERS: The stage was a little triangle and was so small, we sort of had to stand in front of one another; so Woody was at the back, then it was me, then Chris stood in front of me.

SUGGS: Like any young band, we were still just kids learning how to play, but performing eyeball-to-eyeball with a crowd in places like the Dublin Castle was where we really learned how to entertain. It’s all very well writing songs in isolation, but when you see an audience reaction, you start to learn what they like and don’t like. It gives you direction and you learn how to perform. It was there that I started to get my confidence. If The Beatles got their thing going in Hamburg, then the Dublin Castle was our version of it, except without the girls. Without it we wouldn’t have made it, I’m sure.

MIKE: We definitely found our mojo there. It was great – it really helped us a lot.

SUGGS: When we started playing that kind of ska, we knew we were onto something different. It had something infectious. When we started dropping Madness and One Step Beyond into the set we noticed that it really got the crowd going. But we never made a big thing about ‘doing it for the people’ – it was basically for ourselves. We were playing to our strengths and our strengths were pretty limited back then. If we could feel we could dance and be excited by it, that was enough.

BEDDERS: I remember Chris sitting me down and giving me a talk about pulling my weight. It must have made an impression because I can still remember it. He’s good at putting things in perspective.

WOODY: I remember my mum saying, ‘You’ve got to get rid of that singer – he’s terrible’.

SUGGS: And I remember we were terrible that night at the Dublin Castle, absolutely terrible. We very patently weren’t a country and western band. But Alo sold a few pints that night and on the back of that we managed to get a three-month residency. I remember Lee saying, ‘That’s it. If it doesn’t go any further, we’ve still made it.’ It was the turning point and meant we could start to build a following.

WOODY: The DC had previously only ever had a couple of Irish jig artists; an old bloke doing Irish songs or a couple of jazz quartets or something. Then once we got our residency, we were packing the place out week after week.

FEBRUARY 22: The Music Machine, Camden Town , London

Read more

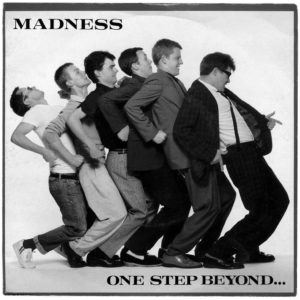

Playing in support of Sore Throat – whose keyboard player Matthew Flowers is a friend of Chris – the band are billed as Morris and the Minors, but with a few hours’ notice they change their name to Madness, after the Prince Buster hit. Carl joins the band onstage to dance.

setlist

Sunshine Voice / Roadette Song / Rich Girls / My Girl / Tears of A Clown / Mistakes / Steppin’ Into Line / Madness / Razor Blade Alley / Memories / Believe Me / Swan Lake / ENCORE: One Step Beyond / Rockin’ in Ab / I Lost My Head

LEE: We were offered a support at the Music Machine, where the BBC had recorded radios comedies in the 50s and where Charlie Chaplin had performed before. My granddad was a fan of the Bedford Music Hall opposite. Sore Throat, a band I had seen on many occasions, headlined. They were good but we played and performed better. The amphetamines may have played a part.

ANNE MARTIN (aka Bette Bright and the future Mrs Suggs): I was dragged off to see Madness at the Music Machine by Clive Langer. I thought the band were good but I thought the singer was a little bit pear-shaped. I soon changed my opinion.

MIKE (writing in his diary): Some people said we blew them off stage. We had a good support from the crowd anyway.

CHRIS: Another band called The Invaders had come along who had a major deal, so Mike had the bright idea of calling us Morris and the Minors. No one dared to argue with him as he owned the Morris van that we used.

MIKE: We did one gig as Morris and the Minors. I’m afraid I’m guilty of the name – no one else liked it. I had a Morris Minor van; a typically English van. A lot a bands in those days had names like Elvis Costello and the Attractions, so I thought Morris Minor and the Majors. Being a sort of following type of guy, following what is happening, you know. But nobody else liked it so it got knocked on the head.

LEE: Suggs said he didn’t want to be Morris, and we certainly didn’t want to be the Minors, so we threw a few other names around, like The Soft Shoe Shufflers.

WOODY: We were also going to be The Big Dippers weren’t we?

BEDDERS: Yeah, that was another possibility. Suggested by Lee.

LEE: In the end we settled on what was right at the end of our nose.

CHRIS: While discussing this sad name, someone said, ‘Let’s pick one of our songs’. Suggs had brought a scratched version of Madness along to a rehearsal and we’d put it in our set, so as a joke I replied, ‘Yeah… like Madness.’

LEE: We were all like, ‘Yes! There it is!’ And Chris was like, ‘No, no, no – I was only joking.’

CHRIS: I thought it was a bit shit but it was too late because everyone else was going, ‘Yeah! Yeah! Right!’ And the rest, as they say…

SUGGS: We thought, ‘Madness – brilliant!’ I think it’s a brilliant name, because you can be mad in a million ways: Madness can be quite sane, or completely over-the-top, or it can be just funny, or really serious. Chris was the only one who didn’t like it.

CHRIS: I thought it was the kind of thing for an Alice Cooper-type band. But it stuck.

SUGGS: Mike said, ‘It sounds a bit novelty’ and I said, ‘No more novelty than Morris and the Fucking Minors.’

MIKE: Everybody thought it was good and said they could live with it. It was the only name no one had any objection to. If he hadn’t spoken up, we could have ended up being a serious band.

SUGGS: We’d never thought about the connotations particularly, even though we were all mad.

CARL: Madness just seemed to represent us as a whole.

WOODY: My mum was an AFM – assistant floor manager – at Top of the Pops, so she used to know all the pluggers. Once we’d made the decision to be called Madness, she excitedly told them all. To a man, every one of them went, ‘Oh, what a shame. They were gonna go so far.’

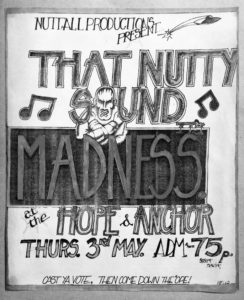

MAY 3: Hope & Anchor, Islington, London

Read more

Madness sell out the first show in the basement of their spiritual home after Carl and band pal Si Birdsall pester club manager John Eichler for months. One Step Beyond is now part of the newly-named band’s set. The show takes place on the same day the Tories win the General Election.

SUGGS: We’d been going to the Hope long before we made a ripple on the local scene because the music on the old Wurlitzer was the best in town. John let us put our own selection of obscure ska and Motown on it, and the pub became our unofficial HQ. We were using it as a focal point, meeting up there regularly, monopolising the jukebox. It was possibly the most important place we came to because it was the best live music venue in the area, even though the basement bar was smaller than the DC and held no more than 50 people. Ian Dury, Dire Straits, The Pretenders… everyone played the Hope. If a gig wasn’t sold out, John would let us in for free.

CARL: We used to spend a lot of time at the Hope, so it seemed the obvious place to play. We got the gig by taking a tape around. We told John that we were a band and he didn’t believe us. That’s the kind of relationship we had.

JOHN EICHLER: They’d brought in a demo tape which sat around in the office for a while. After a week I played it and I was really surprised. It was quite reasonable – not brilliant – but for me it was as real treat to hear somebody playing ska, because it was one of the things I danced to as a teenager in the 60s. We didn’t have anybody on that Sunday so we bunged them on.

BEDDERS: It was our sort of first step into becoming a proper gigging band. Admission was 50p and we made £40 on the door….

SUGGS: …and then I accidentally put my foot through one of the monitors on the PA system, which had cost us £45 to hire.

BEDDERS: Luckily, out of the goodness of his heart, John gave us the extra fiver to make the money up.

SUGGS: He was so kind – he didn’t want to see us go home starving.

JOHN EICHLER: Their show itself was raw, untogether, but loads of fun. They obviously had guys with talent in there. Mike’s mum was a music teacher, so they had a musical background. But what other band would have two mates as dancers? Screw the drummer, make sure we’ve got the right nutty dancers on stage!

SUGGS: I think had been my idea to include One Step Beyond as it was one of the old Prince Buster records we used to play on the pub jukebox. I was 15 when I first heard it. That and its A-side, Al Capone, had been gathering dust in an otherwise modern jukebox in a Tottenham Court Road arcade. Me and Chalky used to go there to play pool and would put both sides on in constant rotation, much to the consternation of the owner.

CHRIS: I remember hearing Al Capone for the first time – the whole sound was so strange; it was something I hadn’t heard before.

SUGGS: Al Capone was an amazing track – it inspired The Specials’ first single, Gangsters, with shouting and machine guns and all – but One Step Beyond had the greater allure for a young man who’d never been abroad. Its lazy, smoky saxophone conjured images of dusty rooms in the casbah. Why Prince Buster was exhorting his cohorts to go ‘one step beyond’, I never did find out, but it always had one foot off the ground.

PRINCE BUSTER (One Step Beyond writer): It’s about getting one step beyond the ghetto, lookin’ up, settin’ your sight higher than where you are. There’s nothin’ wrong with bein’ in the ghetto, livin’ where you live, but you know that you gotta reach out, go one step beyond.

MAY 4: Nashville Rooms

Read more

Madness support Sore Throat in their second gig under their new name.

CARL (speaking in 1979): The only label we want applied to us is ‘That Nutty Sound,’ because there’s no one label that describes us as well as the one we thought up.

LEE (speaking in 1979): It’s a sort of happy fairground sound with jokey lyrics. Almost like Steptoe and Son music. It’s something that we haven’t really got as yet. The only thing that’s really nutty about us is our act and Chas Smash. But the sound is not quite there yet. We ain’t quite sure of ourselves at the moment. When we’ve done a few more gigs we’ll be a bit closer.

CARL: The whole ‘Nutty’ thing was just a natural progression really – it just evolved from Lee writing ‘That Nutty Sound’ on a Levi jacket in bleach and became something more than it was intended to be. We were all heavily into reggae. We also enjoyed the energetic dance rhythms of Motown, the three-minute melodies of 60s pop and loved the comedy of Morcambe and Wise. So put that in the pot and you’ve got the nutty sound. It was a term to express ourselves and avoid being pigeon-holed, because after all we were just kids enjoying ourselves.

SUGGS: We started using the word ‘nutty’ as a term of admiration for the people that didn’t fit into the accepted idea of normal life. Certainly all the greatest things come from people that are mad, there’s no doubt about it.

MIKE: Lee definitely coined that whole concept of The Nutty Boys. He used to talk about our music being a mixture of pop and circus. Then when he came to rehearsals one day with ‘That Nutty Sound’ on his jacket, it looked smart and cool and everyone was impressed.

LEE: When Mike saw it, it was, ‘That’s it! That’s what we’re gonna be!’ ‘What are we gonna be?’ ‘We’re gonna be… Morris Minor and The Majors’. What?

MIKE: There was no explanation, no discussion. Just there it was on his jacket – ‘That Nutty Sound’. I really liked the term. He just had this theory in his head for some of the music we were doing.

LEE: Unfortunately, the bleach burned right the way through the jacket. Three washes later and the bottom fell off; it just frayed to fluff.

CHRIS: Calling our music ‘The Nutty Sound’ was a way to avoid categorizing ourselves. ‘Nutty’ was just a word Lee used a lot, and someone picked up on it. We were very careful never to repeat ourselves and never wanted to be stuck in ska.

BEDDERS: ‘The Nutty Sound’ was all the different things we mixed up in our songs, done our own way.

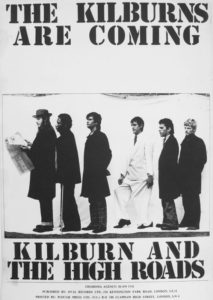

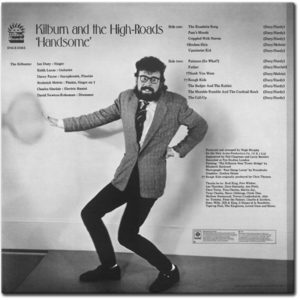

LEE: Get yourself a pot, stick in a little bit of Kilburn and the High Roads, a touch of The Coasters, Fats Domino and Prince Buster, a smidgin of reggae and a good bottle of Steptoe and Son. Give it a good old stir, add a handful of lyrics that are pretty quirky and not the norm and that, to me, would sum up the Nutty Sound.

WOODY: It was exciting for us to get up and enjoy the music with everyone dancing their bollocks off and having a good time – that’s what ‘Nutty’ was about. We were never a political band. We weren’t like The Clash or Sham 69. We saw our music purely as entertainment, and our only concern was that everyone enjoyed themselves.

LEE: The idea was just to keep the music fun and humorous, almost as a rebellion against the punk thing. We always wanted to keep music away from politics. Music should be fun and, above all, loving. I was never a punk for that reason. I wouldn’t give it an inch because of the way they looked, the aggressiveness and everything.

CARL: We used to send out a little Xeroxed piece of paper to record companies which said, ‘Six musicians have been practising in secret and have finally mastered The Nutty Sound.’ It was just something we said at the time to define us and not be put in any other category; Mod, skinhead etc.

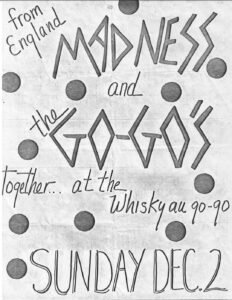

MAY 5: The Specials, Hope & Anchor

Read more

The band decide to check out The Specials after they mention Madness in Melody Maker, saying they’re the only other group in Britain playing the same kind of music. Struggling through the crowds afterwards – Mick Jagger included – Suggs and Mike rush over to talk to Jerry Dammers. He tells them he’s trying to set up his own label called 2-Tone, which he can sign other bands to. With no bed for the night, Dammers ends up kipping on Suggs’ floor and, as a thank you, offers Madness a support slot in London the following month.

CARL: We woke up one morning and realised there was a musical movement and we were part of it.

BEDDERS: We’d all read about this Coventry band that was also playing ska stuff. I realised that I’d actually seen them play as The Coventry Automatics with The Clash in London when they were more punky, although they did have a reggae element to them. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, this lot are quite good.’ I never really thought much more about it until their reviews started appearing.

SUGGS: I’d seen a half-page article about them in the Melody Maker and was really shocked by how similar they looked to us, which was hats and suits and all that. And secondly, reading the article, they seemed to be doing exactly the same music as we were doing. We’d felt we were completely in our own world; just me and 15 other people who’d started our own thing, playing ska and reggae and R‘n’B. Then suddenly a poster appeared in the Hope saying that The Specials were performing and it really was an epiphanal moment. On the night, a strange-looking gang of fellas burst in, all smart suits and Frank Sinatra pork pie hats. They took one look around and filed back out again. Then they reappeared, carrying guitar cases and a drum kit. It was all a bit wary, a bit, ‘Who are you then mate?’ and all that. The jukebox was the catalyst for our first conversation.

HORACE PANTER: My first introduction to Madness was some graffiti on the toilet door at the Hope: ‘Madness, Bluebeat and Ska’. I also remember seeing ‘Chalky n Suggs ov Chelsea’ scraped into doors and walls.

JERRY DAMMERS: We’d been intrigued by graffiti around Euston station: ‘North London Invaders’, ‘Chalky’, ‘Toks’ and ‘Bird’s Egg’. Later, I realised this was the work of Madness and their road crew.

BEDDERS: The gig was sold out, but knowing the governor, John, we managed to blag our way in.

SUGGS: We were intrigued and piled downstairs. It blew our minds to see these people who looked a bit like us and sounded a bit like us. That night was probably my most memorable gig – they went off like a packet of crackers. I remember Neville Staple blowing holes in the ceiling with a starter pistol, then they stormed into Gangsters. Within seconds of the first chords they were jumping up and down like lunatics. They were fucking brilliant, doing this really high-energy turbo punk ska. I wasn’t sure whether to feel jealous or fucking vindicated, that we were onto something after all. It was probably one of the best gigs I ever saw, certainly one of the most important for me and the rest of the band, and completely informed us, in terms of performance, pretty much from then onwards. All that energy they had.

MIKE: I remember thinking, ‘Wow. It really sounds like those old reggae records that we’re trying to do.’ It was so weird. How could this be happening in Coventry while we’re doing our thing in London? We didn’t know anyone from Coventry and yet at the same moment, they’re suddenly coming out with the same stuff at the same time.

WOODY: There was us in London and The Specials and The Selecter in Coventry; two completely different parts of the country, and both ironically influenced and playing music from a part of history. We had the same dress sense and were all listening to exactly the same stuff – it was just incredible. They couldn’t believe that we were into the same things as them either.

LEE: I never had a pot of glue that this was going on up in Coventry, but while we’d been in our bedrooms and doing our first gigs round at our friends’ houses, it turns that there had been this band up there playing the same style of music and dressing the same way too.

SUGGS: I was shocked to meet them as I didn’t think anybody in the world was doing the same thing as us. Because we liked reggae and ska and other music with black influences, as well as the Rude Boy ethos, we thought we were pretty individual. There really weren’t many other people around who were into it until The Specials popped up, but it was a complete coincidence. They were the ‘it’ band because they were one of the first to have black and white members. So they weren’t exactly the same as us, but they were wearing suits and hats and stuff at a time when…

CHRIS: …suits and hats weren’t in.

SUGGS: Exactly. And a whole ball started rolling that we had never really envisaged. We’d been quite happy in our own little bubble, but suddenly we realised something was really going on. There was real excitement in the air; a very rare thing that I’d only experienced once before, in the Roxy. A real feeling something was happening and that we just happened to be right in the middle of it.

JERRY DAMMERS: I just remember that the Madness mob had a dance which consisted of head-butting each other.

SUGGS: Things started to change after we saw them. They were like us, but turbocharged. We were still diesel at that point. They’d gone that bit further, while we were still doing a bit of R&B. The Specials gave us this revelation that the uptempo stuff was really fucking exciting. No one else seemed to have realised what a fertile vein that music was, how potent it was live. But suddenly we were aware we were not alone and we learned a lot about how to turn a basically easy-going rhythm into something quite high-octane and speedy. So they were mixing reggae with punk, while we had the idea of mixing it with British pop music

CHRIS: The Specials were similar to us but they were more punk – they were more influenced by that. I used to really like it but it didn’t really influence us. The thing about The Specials was that none of them had really been skinheads, whereas we had. But I think Neville and Lynval, they were Jamaican, and Jerry had always liked reggae music. That’s how they got into it. It was just a real coincidence. People always used to say that The Specials were the first ska band or some crap like that, but it wasn’t true, it just happened like that.

SUGGS: After the gig I got talking to Jerry, who was talking about the new label he was starting, which he said was going to be an English Motown. Then he told us he didn’t have anywhere to stay, so he kipped at my mum’s flat above Maples, the furniture shop. In those days, your best chance of finding a place to stay after a gig was pulling a bird. But if you’ve seen the state of Jerry’s teeth you’ll realise why he ended up kipping on my mum’s sofa with all his worldly goods – one toothbrush and a few cassettes – in a battered school briefcase. I played a him a rough cassette of Madness and we talked long into the night about pop music and his vision and future that was to be 2-Tone. He was talking about it being self-sufficient, all-encompassing and racially integrated, which was an unusual prospect at that time. It was pretty momentous, but I didn’t think it would ever happen.

BEDDERS: Jerry had been in lots and lots of bands and he’d actually known a bit about the music business. We felt it quite lucky that we had found someone who was a musician and who also knew a bit about the record industry. Everything really sprang from there.

CHRIS: We gave them a cassette – a rehearsal tape, really.

BEDDERS: Jerry says he still has it. He told me he still listens to it once in a while and has a laugh.

JERRY DAMMERS: The tape was dodgy – really, really bad – but I also thought there was lots of potential. I don’t believe any other record label would have signed them at that time in their career except for 2-Tone. They were ropey around the edges, but Chas was doing some amazing dances.

BEDDERS: Jerry said he’d heard about us too, and some arrangement was made to do something the next time they were in London.

JERRY DAMMERS: They were ropey as hell – still virtually a school band – but obviously they had to be snapped up for our fledgling label. My idea was that, instead of competing, we should work together with like-minded bands.

BEDDERS: We said, ‘Look, we’re playing kind of the same music as you are – reggae, ska, whatever’ and Jerry said, ‘Well we’re gonna get a label together and you’re gonna be on it.’ It was absolutely brilliant and incredibly exciting… the right place, right time moment.

LEE: Jerry was like, ‘I’ve got a label, do you want to release a record? Suggs said, ‘Yeah, alright’. And it was that easy.

CHRIS: It sounds so clichéd; if you saw a film of it you’d think, ‘That can’t be true’ but it really was as simple as that.

SUGGS: They were pretty dark times at the end of the ’70s in the UK, which helps explains the rise of punk music, and you had this racist stuff going on as well. But all of a sudden this mushroom of hope, 2-Tone, sprouted out of the darkness.

JERRY DAMMERS: It was obvious the Mod/skinhead revival was coming and I was trying to find a way to make sure it didn’t go the way of the National Front. I idealistically thought, ‘We have to get through to these people’, and that’s when we got the image together and started using ska rather than reggae. It seemed a bit more healthy to have an integrated kind of British music, rather than white people playing the two.

SUGGS: There was a lot of energy and an idea that music had got a bit pretentious and self-indulgent and it was time for something for really young people that wasn’t manufactured.

NEVILLE STAPLE: Jerry was determined to show black and white people together in harmony; even the famous 2-Tone logo was made in black and white to depict racial unity. All of what happened with the 2-Tone scene was the foresight of Jerry and he should be given a lot of credit for the positive social impact he created.

JERRY DAMMERS (speaking in 1979): It’s not that we’re just trying to revive ska. It’s using those old elements to try forming something new. In a way, it’s all still part of punk. We’re not trying to get away from punk. We’re just trying to show some other direction… you’ve got to go back to go forward.

MIKE: The 2-Tone attitude was similar to punk: it was good not to see any hidden mystique in music or to believe you have to be really good to play it. I hate the attitude that there’s something special about music or musicians. I think anyone should be able to have a go at it. At the time when the punk thing came along, you’d think you had to be playing for five years before you could make a record. I used to think that we sounded all right live, but it didn’t seem to connect that therefore we could make records – there seemed to be some magical difference. But there’s nothing particularly special about making records. If you’ve got a good idea at home then it can be a good idea on record.

MAY 7: The Windsor Castle, London

Read more

Only eight dodgy types turn up for this loss making experience. Lee asks the biggest of them to collect their fees. Each band member gets 50p.

MIKE: We got there and we weren’t booked. That was maybe why nobody came. And they didn’t want to let us play.

CHRIS: No, we definitely were booked. It was funny – the week before, in the Hope & Anchor, it was really rammed and I thought, ‘This is it, we’re really going somewhere.’ But we got to the Castle and only Mike’s mum and about three other people turned up. And then when we hit it big, the owner of the pub was like, ‘Ah yeah, they were in here all the time, lovely boys.’ Hah! We certainly paid our dues.

SUGGS: Laughter was the binding factor. Our humour was all about surreality; Tommy Cooper, John Cleese, Benny Hill’s speeded-up sketches. We talked about things being ‘nutty’ to give it some kind of shape. We were all very keenly against pretension. Motown was our template – three minutes of fantastic pop music with a bit of style and a bit of an idea behind it.

BEDDERS: The things we enjoyed were Joe Orton’s Loot, Tommy Cooper, Tony Hancock, Ealing comedies. Madness have always had more in common with comedians than musicians, so it was no surprise that we funneled that in to what we were doing. We came from not only loving music but loving comedy, and a kind of comedy which had a feeling of down-at-heel melancholy, which always found its way back into the songwriting. There was also an identification with those parts of Britain, and London particularly, that even then were disappearing.

SUGGS: We definitely sat somewhere between Peter Cook, Ian Dury, The Kinks and Prince Buster.

CARL: There was definitely always a touch of Tommy Cooper about us. In terms of our world view, we were slightly to the left of stage. We might have appeared bonkers but, by writing about everyday subjects in a completely honest way, we connected with people.

MIKE: We were, and are, a pretty ramshackle mob. Everybody in the band’s a bit out to lunch. And because you have to know what you’re presenting, it needed a bit of organising.

SUGGS: There was a very complicated synergy. We all had a lot of energy and everybody contributed something. Most of the band never took drugs, but psychedelics had played their part with some of us; that a culture was not alien to us. You didn’t have to become a hippy and lose your mind completely, but you could understand that side of the mind and put that into three minutes of pop music. Later, the videos had that surreality, which some-times did take them to the verge of being a bit dark. There were definitely a lot of funny, intelligent characters in the band, in an uneducated way.

MIKE: We were a band with character and talent but none of it was false or fabricated – we are who we are. Some of the group likes showing off more than others but that also helps to strike a balance.

WOODY: We liked bands like Roxy Music, who had something about them. We weren’t fans of people who just looked at their shoes. Saying that, we never wanted to do show off and ten-minute guitar solos, mainly because at that stage we were just about competent, not up there in the heights of ‘let’s see if we can do a flat-diminished-fifth’. We were lucky if we could remember the chords and could go from the beginning to the end of a song. That was our only aim. So we couldn’t take ourselves seriously.

JUNE 8: Nashville Rooms / Dublin Castle

Read more

The night’s first show – supporting The Specials in front of 500 people – stirs so much interest that ticketless fans cause a riot and have to be dragged out by cops. An impressed Dammers offers Madness a contract for releasing one single on 2-Tone. Due to this earlier support slot, Madness nearly miss their gig at the Dublin Castle in front of 300 people – the first of their regular residency shows. Lee asks Carl to announce Madness, which he does with a speech based on the intro of Prince Buster’s Scorcher and Dave & Ansel Collins’s Monkey Spanner. Rather than leaving the stage afterwards, he stays to dance.

First-ever gig review

THE NAME says it all. Shut your eyes and think of England’s entire phalanx of pop culture during the last say, 25 years: teds, beatniks, rockers, mods, skeds, hippies, glam-rock mutants, Sloane Rangers, uniform fetishists and main-line punks. Now imagine 20 or 30 of each strain, plus several dozen left-field crazies I’ve misplaced pigeon holes for, huddled together in a room the size of your average khazi, simmer at a steady Regulo 6, and you’ve got the Dublin Castle last Friday night.

This, I’m told, is a typical Madness audience, and I brace myself for the ultimate cross-over band.

Instead we get six fairly nondescript teenagers, the only visual heretic being Mikey Barson, who wears a bootlace tie, a dirty tux and exudes sleaze behind a set of keyboards. Huddled around him on the titchy stage are Lee Thompson (tenor sax), Mark “Fiddly” Bedford (bass), Chris Foreman (guitar) and a big lad called Suggs who sings. All, save Barson, have closely cropped barnets and look vaguely threatening, but this turns out not to be the case.

Suggs is a natural showman, a street-level raconteur who keeps up a constant stream of personalised banter with his audience, dedicating almost every number to someone or something, each more laughable than the last.

Vocally reminiscent of Kevin Ayers, his original songs have a strong blue-beat feel, and he’s even written one extolling Prince Buster, called ‘The Prince’, but his style and delivery is closer to Johnny Moped.

Shuffling like Terry Dactyl & The Dinosaurs, or grating listlessly like Sky Saxon & The Seeds, they defy tidy comparisons. Just when you’ve got familiar with Barson’s jangly, fairground organ or Thompson’s affable, knockabout sax, the former dons an England supporter’s beanie and careens into ‘Tears Of A Clown’ or the latter has a crack at ‘Hall Of The Mountain King’ as if Greig had written it after cranking up a gram of sulphate.

By the third encore, half the punters were jumping on tables waving clenched fists, and the other half were reeling about the glass-strewn floor, jolly pissed. Catch Madness supporting the Specials A.K.A at the Nashville next week, and you may find yourself similarly disposed.

Mark Williams, Melody Maker, June 13 1979

CHRIS: We were double-booked as we had already confirmed the Dublin Castle gig but we didn’t want to miss the chance of playing with The Specials.

HORACE PANTER: Madness, who were now not just a name on a pub bog door, nervously opened the show. The place was packed to the rafters; there was a queue right round the block.

SUGGS: The Nashville gig went in a blur of pumping arms and legs, the odd pork pie hat floating in a choppy sea of cropped heads bobbing up and down. We went down great. We were obviously in competition with Jerry and co – albeit very friendly competition – but playing together like that was truly thrilling. It was just exciting to know there was another band doing what we were doing. Jerry said he really enjoyed it, but there was no time for back-slapping as we had to get north and sharpish.

CHRIS: It was hard to get out of the Nashville, as it was so packed.

SUGGS: When we finally got to the Dublin Castle it was pandemonium. Every table had three or people standing on it and beer was flying in all directions. As soon as Carl’s rallying call ‘Hey you!’ went up, the place went ballistic.

CARL: If the Mads had never covered One Step Beyond I probably wouldn’t be writing this now. Because I could shout loudest, they started to let me yell ‘One Step Beyond’ a few times before kicking me offstage. After a while I got well pissed off at being kicked off, so I started moving about avoiding them. Everybody thought, ‘Wow a new dance’. I haven’t stopped moving yet.

SUGGS: Carl came up with the intro: ‘Hey you, don’t watch that, watch this…’ It was inspired by the shouty, slightly preposterous ‘I am the magnificent…’ intros you got on Jamaican records.

CARL: I’d been working in Kent and Lee had asked me to travel up to London and introduce the band onstage. On the train, I wrote out the ‘Hey you!’ words that formed the intro to One Step Beyond. I’d also developed a persona and started to become that Chas Smash character as a sort of the mascot – the physical representation of the sound. I shape-shifted into what was required – a bombastic frontman, the spirit of the band, the seed. I was having a lot of fun and I wanted to stay there, but at the same time I was also extremely shy and never took the dark glasses off; I was on speed at all the early gigs to give me confidence to go on stage.

JUNE 15: Dublin Castle

Read more

The band get friendly with Clive Langer, a school pal of Mike’s brother Ben, who agrees to produce their demos.

CLIVE LANGER: I’d come to London with Deaf School and seen Mike and his gang watching us. My first memory of him was of this little kid who was good at art and also pretty good on the piano. His whole gang looked really good – kind of glam mods, spray-painted DM boots, 501s. I was 24 years old and I think they ranged from about 17 to 20. It was pre-Carl, although he was still hanging around a lot of the time. They’d meet up backstage and tell me that they were starting a band called The North London Invaders, and ask if I wanted to check them out. They were the best-dressed kids from north London and they were Deaf School fans, so I offered my services.

MIKE: One night Clive got pissed and said, ‘If you ever record, I want to be your producer.’ So we held him to it.

CLIVE LANGER: At the first rehearsal I went to, John Hasler was repeatedly throwing a flick-knife into a pillar. I thought it was a bit weird. But you could tell it was potentially brilliant – My Girl in particular just jumped out at me. At the time, Mike was singing it, which didn’t sound right. But I knew he was a Robert Wyatt fan, and I loved Robert Wyatt, and it was like one of Robert’s songs, a naïve love song with a great melody. It was just amazing song. A lot of other elements were already there too. Woody was obviously a good drummer and Mike a great rock piano player, really hitting his piano hard. The rest of the band were a bit rough around the edges, but were all nearly there.

ROB DICKINS (Warner Music): Clive said, ‘I’ve found a band I want to produce. They’re called Madness, they’re sort of like The Specials,’ who were the hot A&R thing at the time. He said they were fabulous, had a humour and energy that he loved and he thought he could capture it. I’d seen bits in the music papers saying they were a Specials rip-off, quite demeaning, so I said, ‘Are you sure?’ He said, ‘Yes. I’ve seen other things but Madness are special.’ I was thrilled.

SUGGS: It was a real whirlwind, that time. Clive used to come down to rehearsals and encourage us in readiness to make a record. And then our gigs became more packed, and then record companies showed interest. And then The Specials came and it really exploded and we happened to be right there when it exploded.

WOODY: When there’s queues round the block for your gigs, it says something. OK, we did know a lot of people and we did have a lot of mates who turned up at gigs to make it look good, but it was clear we had something about us.

SUGGS: And this whole thing was word-of-mouth, of course. You couldn’t pick up a fashion magazine to see what the latest teenage trend was going to be. It just sprang up organically across the country. You’d go to a town and there would be rockabillies, psychobillies, punks, mods, teds, soul boys, skinheads. You’d get off the train and know that you were somewhere new because the kids were wearing stuff that was very different to what you were wearing and you could only get in that area. I remember in Liverpool they had Stan Smith trainers that no one else had seen before.

JUNE 22: Pathway Studios, Islington

Read more

Clive Langer gets £200 from Warner Bros and the band go into Pathway Studios for the first time (an earlier demo session is cancelled after Woody gets lost on the way). They record Madness, My Girl and a new song written by Lee called The Prince. The recording and mixing takes place over one weekend.

WOODY: We didn’t have the money to pay for a recording, so we borrowed some off Warner Brothers, gave them bit of our publishing, and off we went.

SUGGS: Clive duly booked two days at Pathway as he thought that would be just enough time to record three songs. It was decided we would have a go at The Prince, My Girl and Madness. We went to Pathway because it was where The Yachts had recorded their first single and where Elvis Costello had recorded Watching The Detectives, which we were all very fond of.

LEE: Because we still had proper jobs, there wasn’t time to fuck around. We were actually booked in for the previous week but we lost Woody, who wasn’t familiar with the area.

SUGGS: We’d piled all our gear and ourselves into Mike’s trusty ex-GPO Morris 1000 van and set off.

CLIVE LANGER: Woody was going to meet us there as he had this little motorbike, but he got lost en route.

CHRIS: We were in Holloway Road and he said, ‘Oh I know where it is.’ And off he went, never to be seen again.

SUGGS: So we lost the first day’s recording and our cash, which wasn’t the most auspicious start to our professional career. But Clive managed to draw on Rob’s enthusiasm to borrow some cash and extend our recording time.

CLIVE LANGER: I went and saw Rob Dickens who lent us an additional £200 for another session, and this time it all worked out well. Producing-wise, I was still pretty green, but I had some idea of what I was doing.

LEE: Thanks to Clive wangling the advance, we put down three tracks, two of which were eventually used on our first single.

SUGGS: We recorded The Prince, My Girl with Mike singing, and Madness. The studio was tiny, with a slightly out-of-tune upright piano. There was barely enough room for us to fit in. The atmosphere was great and the tracks were sounding good. With a couple of hours to spare at the end of the day, it was just a case of mixing them down. This involved three of us pushing faders up and down as the songs went onto the two-inch tape, until we felt the right balance of instruments and vocals had been achieved. Which at about midnight we all did. We then took it turns to sit in the control room and listen to the tracks on the big speakers. We all agreed they sounded great and spent an hour or two recording the mixes onto cassettes, one at a time, so we could all take the songs away with us. Happy days; really joyful, innocent times.

LEE: The title track, The Prince, was a tribute to yours and mine, ruler of Blue Beat, F.A.B. and Dice recordings, Mr Rude Man himself, Prince Buster. It was written over a cuppa and dunkies late one evening at Carl’s in-laws’ house. We had a cup of coffee… and another cup of coffee… and another cup of coffee… and wrote this track about a Jamaican artist who moved me. It was the first lyrics I ever wrote to a melody.

BEDDERS: I think it was written pretty late in the day. Lee wrote it pretty much thinking that we were going to go and record something.

CHRIS: Because Lee really liked all that stuff, there’s lots of references to Buster himself, Orange Street, uptown Jamaica – it’s a bit of a rip-off of a couple of Prince Buster songs.

BEDDERS: It’s almost like a compilation of Prince Buster songs.

CHRIS: Lee also did this saxophone solo which we were really surprised by because it sounded so professional. But of course he’d pinched that too.

LEE: The lyrics were taken from bits and pieces of various Prince Buster songs. Because he’d always stood out to me, when I started writing I took elements from his work and put them together. The melody was a simple 12-bar with some odd bits thrown in for variety but I was stuck for a solo, so I played bits of Texas Hold-Up. Its flip side was a version of Prince Buster’s Madness.

BEDDERS: It’s a fantastic idea and a fantastic song. It reminds me of Dancing In the Street because it’s a call to people to say, ‘This is what I really like. This guy should be looked at and we should all get out there and find his record and dance to it and play that kind of music.’

CHRIS: After Lee wrote that, and because Mike had written My Girl, I just remember thinking. ‘Great they can write all the songs, I don’t need to worry.’

MIKE: When we went in the studio to record it, I was quite knocked out with how The Prince sounded, ’cos what we were came out pretty well. It was bizarre. We were really only half-able to play a song, and I was a bit afraid that we weren’t good enough to appear as a recording group, yet suddenly here we were getting noticed. And we’d barely mastered our instruments!

CHRIS: Clive Langer was a big help during those first sessions. He was really good – like another member of the band. Because he was a musician himself, he’d say stuff like, ‘Look, try this on the guitar.’

LEE: Yeah, Clive really simplified things. God only knows what it would have sounded like without him.

ROB DICKINS: Clive comes back and says, ‘I need another £20 to do a remix’. So I gave him another £20. He comes back with The Prince which Lee had written, My Girl, which Mike had written, and Madness. And I went, ‘Clive, Madness is a Prince Buster song! What happened to three songs?’

MIKE: Amazingly it sounds like a professional recording but it was very close. It was by the skin of our teeth that we made that. In fact, it was all by the skin of our teeth. It was like an airplane taking off and we weren’t packed or anything and we just managed to jump on as it took off.

SUGGS: Jerry had always promised me, ‘If you ever get your band going, then you’ve got a chance of being on the label’. And he stuck by his word. When he heard The Prince he said, ‘It sounds great. I’ll put it out on 2-Tone.’ And everything went from there.

WOODY: The Specials had blagged a record deal with Chrysalis, and just said to us, ‘We’ve got a record label, do you wanna do a single?’ It wasn’t anything earth-shattering – it just happened. By this time, there were lots of record companies sniffing around, so I think we would have signed with someone anyway.

ROB DICKINS: I remember they came to me and said, ‘The Specials have offered us a deal so we can get this out on 2-Tone.’ I said, ‘Oh, forget 2-Tone! You don’t want to be there as second cousins to The Specials. I know everyone at the major labels. I’ll get you a record deal.’ So, I went to Warners and they didn’t get it. I went to EMI and they didn’t get it. I went to all the labels, even including Stiff, and couldn’t get them a record deal. So we had a meeting in my office and I sheepishly said, ‘I’m broken! This is ridiculous!’ I said, ‘Do you think 2-Tone would still be up for it?’ So they said, ‘We’ll go and check – yeah, yeah, they’re still up for it.’ So I said, give them the tapes. And that was The Prince.

CLIVE LANGER: I’d also taken the tapes around to people I knew at the big labels in town and no one else seemed to get it. So off they went to 2-Tone.

RICK ROGERS (The Specials manager): I think the first meeting we had was in The Spread Eagle in Camden Town one lunchtime. We talked about the idea of doing a single with them – in fact, putting out the single that they’d already recorded as a demo. Everyone was very happy with it. The A&R decisions tended to be made by a committee of hundreds and there was no dissension.

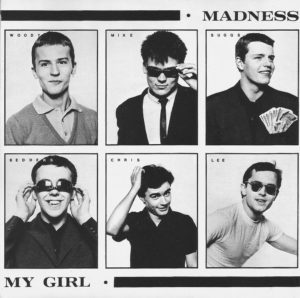

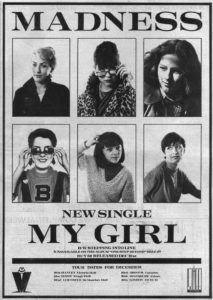

WOODY: We chose The Prince because we thought it was the most commercial of the three that we’d recorded. Madness was a cover version and Mike was singing on My Girl, and we needed a song that Suggs was singing really. It also had the 2-Tone feel and was the most ska out of the three tracks.

CLIVE LANGER: Jerry just told us to turn up the ‘chink-a-chink-a’ rhythm guitars, and the next thing you know it’s a hit and the boys are on Top of the Pops.

SUGGS: All of a sudden, the possibility that none of us were going to have to work for the council or polish cars any more was a reality coming our way across the horizon.

JUNE 24: Hope & Anchor

Read more

Due to overwhelming success, Madness return for another show at the Hope & Anchor. With the British music press mentioning them in the same breath as The Specials, record companies get interested and send A&R managers to the show. Before coming on, Suggs hands out singles to winners of the previous week’s competition. Two cover versions are played in the encore – Smokey Robinson & The Miracles’ Shoparound and Rockin’ In Ab, originally by Bazooka Joe, whose singer is Mike’s brother Danny.

Gig review

Suggs is the real character of the group. Before the set had even begun he was on stage dishing out vinyl goodies to the winners of the previous week’s competition, while the majority of his stage-raps comprised a series of wacky dedications to various mates in the audience. By the time they encored with Shoparound and Bazooka Joe’s (Adam Ant’s punk band) Rockin’ in Ab, the cramped cloisters of this Upper Street basement were converted. And as the Prince Buster song says: ‘It’s gonna be rougher, it’s gonna be tougher’.

Adrian Thrills, NME

LEE: When we played The Hope, I used to frisbee out old ska singles and throw pork pies into the audience. I had a tie which lit up, too (unashamedly nicked from the Kilburns). Do something more than just playing music, make it a bit more visual, save the actual music for the records and concentrate on the visuals, that was an integral part.

SUGGS: At first just our friends came to our gigs, but the audiences just got bigger and bigger and they ended up having to turn people away from places like the Hope ‘cos there wasn’t not enough room. We played dance music but there was never enough space to dance to it in.

CARL: It wasn’t so much our musical quality as our enthusiasm that won audiences over – they’d end up onstage with us half the time.

SUGGS: There was a very strong feeling of mutual respect and camaraderie. This was our thing; we were part of it. We were doing it ourselves and the establishment couldn’t get a look-in. The clothes and music were hard to come by. There was a lot of effort going into this shit from all concerned. It was a feeling I’d only really witnessed as a kid when punk started, but this time we didn’t want to tear our clothes up and leap about. We wanted to look smart and dance.

WOODY: It was all going off – we were all very young and everything was new and exciting. When you meet people who have the same interests as you and the same energy, it is very exciting. You don’t really think about what you’re doing, you just want to play music. That’s all you care about.

SUGGS: I still had a job as a gardener through the week, and was playing at the pub on a Friday night, and I thought, ‘Well that’s enough. You get £50 and a few birds coming to look at you.’ I was quite happy to play one night a week, earn a few quid and then go into work like a hero on Monday.

CARL: We didn’t have the brains to ask a talent scout to come and see us. We used to appear week after week in empty clubs, just playing away. It didn’t really occur to any of us that other people might be interested in listening to our type of music.

CLIVE LANGER: They were very young and just having a laugh — they’d be happy to play in a bar and just get people to dance.

SUGGS: We were playing in a sweaty pub with £5 between the seven of us and having to shift our own gear and everyone was saying, ‘You’ll look back on this and love it’, and we thought, ‘Bollocks.’ But I do really like looking back on it now. Because none of us had been in the business before, we were all very naïve and in our own little bubble.

BEDDERS: When you’re younger you don’t really think about it that much, you’re swept away by the next thing that comes in front of you. I think that’s what kept us going; being youthful and enthusiastic. I’m the youngest but as a band we were bonded together by the speed of everything going off – and we bonded together as a group; the situation demanded it.

SUGGS: I wouldn’t imagine a band of seven people could make it now in the way that we did. Going round in the fucking van with seven of you, working during the week, trying to support yourself, it would be tough. Whatever way you look at it, there are thousands more bands now than there were when we started. You can build up a bit of a following online and get some kind of career going, whereas in our day, you only had word of mouth. It would take months and months to get 400 people into a venue. It goes back to the old adage of hard work and determination. We had to work in gardens during the week or painting and decorating – then we’d go out and do the gigs at night. It certainly didn’t come on a plate.

JUNE 28: Nashville Rooms

Read more

The second show with The Specials in front of 500 fans. After the riots on June 8, it’s now decided to sell tickets in advance. Madness play a better show than before and Jerry Dammers asks them to support The Specials at an upcoming show in Liverpool.

SUGGS: Something we always championed, right from the start, was singing in the accent that’s where you’re from. You don’t do that fake American thing.

MIKE: In those days someone would grab a microphone to sing and this American accent would come out. It was bizarre. But people like Ian Dury didn’t have any of them pretensions.

CARL: Ian Dury was definitely the most direct influence. It’s like Catatonia singing with a Welsh accent. Ian sang in an English accent: ‘Burly Bently walked to London early in the day… half a quid mate, stand to reason.’ You know, it’s alright to sing in your own accent, it’s alright to talk about things that are in your life.

SUGGS: It’s fine to write about the freeway in California and your yacht and all that, but it was more interesting for me to write about what’s going on around me. I don’t think that has to be any less interesting. You know, to talk about some mad geezer you met in a pub, just the things that happen to you in your everyday life – that’s what I was interested in.

CARL: It was quite freeing to know that it didn’t have to be, ‘Baby, I’m a-want you…’ That was definitely a big part of it – that you could just speak about what happened in your life, in a normal everyday way.

SUGGS: To sing in your own vernacular and not necessarily be Otis Redding was a real lightbulb moment. The people who influenced me – Ray Davies and Ian Dury – weren’t necessarily the greatest singers but they had a bit of character. Also, we didn’t understand the process of making records or PR or interviews but because we’d seen Ian Dury do it – somebody with polio – we saw all the possibilities for people who didn’t necessarily look like rock stars. Ian didn’t seem anything like Rock ‘n’ Roll or the music biz; he was more like a poet. So he inspired us to go down that route without actually having to know anything about the music business.

CHRIS: Another thing was, Mike and me used to go and see a lot of groups and they’d always have a keyboard player, but you’d never be able to hear him. So we decided we’d make sure you could always hear Mike because he’s really good – but then no-one could hear me!

JUNE 29: Dublin Castle

Read more

Carl does not appear tonight. The A&R manager of Magnet Records ¬– who will eventually sign Bad Manners – is watching and buys the band drinks afterwards.

MIKE (writing in diary): Same pub, same group, same price, same songs; it seemed like going through the motions. Felt we should be doing new songs. Bloke from Magnet [Records] bought a round. Lots of dancing, though. No nutty Carl.

SUGGS: The Dublin Castle meant everything to us. We could barely play our instruments when we first arrived and they had the heating on so the punters would drink more – there was sweat dripping off the ceiling. For those first few gigs it was 50p to get in, then they decided to put it up to 75p.

MIKE: One night, we made £100 profit. What about that?

BEDDERS: When you start, you know all of your audience. And then suddenly, particularly in places like the Dublin Castle, more and more people that we didn’t know started turning up. We started thinking. ‘Hang on…’ and then it just got bigger and bigger.

SUGGS: We started to notice that more people were coming week after week. Then people started to dress a bit like us. Then suddenly, there was a queue round the block – and that’s when record companies started to notice. It was the most important thing that happened in those early days.

MIKE: You could see there was a bit of a buzz happening. We started to attract some Press interest and got our first review from one of those Dublin Castle gigs, by Mark Williams in Melody Maker. Yet there we were, still using two old Morris vans to get around!

SUGGS: The quote I remember was, ‘By the third encore, half the audience were standing on the table waving their clenched fists, while the other half were reeling about the glass-strewn floor, jolly pissed’. And that about sums it up.

JULY 3: Moonlight Club, London

Read more

With only one PA for the vocals, Suggs and Chris swap places for bluesy ballad Memories.

Set list includes: Memories / The Prince / Land Of Hope & Glory / Steppin’ Into Line / Rockin in Ab / Swan Lake / Shoparound.

Gig review

That these boys are a classy dance band is evidenced by madness and their tribute to its author: The Prince and Land of Hope And Glory. Not to mention the rock ‘n’ roll of Steppin’ Into Line and Rockin’ In Ab. Loads of people danced and had a good time.

Garry Bushell, Sounds

NEVILLE STAPLE: We met a whole new breed of ska fan down in London who were inspired by Madness. There was no doubting they attracted a different sort of fan to us. Some ugly elements turned up to those gigs; bovver boots, bleached jeans and tight little bomber jackets – a nasty kind of uniform.

SUGGS: I remember the fashion back then was really tasty, but for a lot of people it was just Doc Martens, white towelling socks, slightly too tight and too short jeans. I feel slightly ashamed about some of the aspects of fashion we were responsible for – but I’m not as embarrassed as fucking Duran Duran should be.

JULY 6: Dublin Castle

Read more

The last show of the band’s Friday night residency at the Dublin Castle. Mike says things are getting too routine.

CARL: It’s funny that we came to be associated with Camden. It’s even in Trivial Pursuit: ‘Who are the seven nutty lads from Camden Town?’ It’s similar to The Kinks and Muswell Hill or Rod Stewart and Highgate.

CHRIS: Camden was pretty rough back when we started out. A lot of the pubs have changed now.

SUGGS: It was nothing but blokes falling out of pubs and a couple of Morris Minors. It was Irish and Greek Cypriot. On a Friday night there wasn’t a woman in a five-mile radius. You went to Camden to get pissed and beaten up. The only food you could get was a ham or cheese sandwich out of one of those Perspex things they used to have on the bars of pubs or the caff. I can remember a friend of my mum’s having a pie-eating competition in a pie and mash shop. Perhaps there was less to do in those days.

BEDDERS: It was certainly an interesting mix – you still had hippies in fur coats and cowboy boots, and a lot of Teds.

WOODY: You also got full-on, proper skinheads. I remembered them from the 60s but they were coming back again. Camden has so many memories for me. A lot of people say it’s rough and violent. But I’ve lived there all my life and never seen any trouble. I feel very safe there.

CARL: One night this mod stole my scooter – a 200cc Lambretta bought second-hand in ’76 – from outside the Hope & Anchor. The next night my brother saw it. The mod had re-sprayed it in one day from yellow to maroon and grey and parked it back outside the Hope again. He obviously thought I wasn’t a local, so I got that back pretty quick! When all the mods were doing their scooters up really smart, we purposefully made ours really trashy. We’d go to places and all the mods’ scooters would be parked neatly and we’d leave ours on their sides.

SUGGS: We also used to go to this great snooker club in Camden, which sadly has been knocked down now. A lot of professionals used to play there, including Terry Griffiths. It was an alcohol-free club so I think that’s why some of the serious pros were based there. There was a bar next door called the Crown & Goose, and we knew the owner so we got drinks there and then smuggled them into the snooker club. It was a really nice atmosphere and we loved it. We didn’t mind if we only played one frame in two hours, we were just having fun. Carl was the best of us, but none of us were competitive because we weren’t good enough – it was just a way to spend an evening.

JULY 8: Hope & Anchor

Read more

The band end the successful show with One Step Beyond. In the days afterwards there are meetings with EMI and Sire, who offer Madness an American Autumn tour if they sign.

MIKE: Paul Conroy from Stiff came down to see us at the Hope with Kosmo Vinyl, his artistic director. He said we were a heap of shit and kept saying to Paul, ‘No, it’s a wanky group’. Paul said ‘We’ve got Ian Dury already’.

SUGGS: They left halfway through. We were a bit disheartened. We just wanted to make a record and have some proof we were musicians – plus make enough money to go out on a weekend.

JULY 14: Eric's, Liverpool

Read more

Madness team up with The Specials again for their first gig outside London. Although planned as another support slot, both bands decide to switch roles for practical reasons.

WOODY: We’d already conquered Camden Town and the surrounding venues, so when we got offered the chance to go and play in Liverpool, it was an adventure. Going to Eric’s, all squashed into two little Morris Minor vans with all the kit, was such an amazing experience. For the first time I had that big group around me.

ELVIS COSTELLO: The Specials went on first because some of the out-of-towners came to the club, so Madness had all evening to get drunk, and they came on like this gang of football hooligans – completely pissed. They opened with Madness and were absolutely fantastic for one or two numbers, but then it disintegrated into a total shambles. They were like a gang who could play…a bit. It didn’t seem like they could even remember their own songs. That was the first time I saw them and I really thought they were just a novelty act. I thought it could be something that would only work live, but they were really good fun.

PHIL JONES (audience member): The gig was amazing, not so much musically, though they were impressive enough, but it was just the instant joy they brought to the night. We all danced that stupid nutty dance for the first time ever and that, in itself, was joyous.

CARL: I used to do a dance with Chalky to Swan Lake where we would head-butt each other. When we played Eric’s this Scouser went, ‘You’re not really doing it.’ I went, ‘Come on up and have some then mate.’ He went off with a sore head and of course it ended up in a fight afterwards.

CHRIS: Carl and Chalky used to have scar tissue on their heads from doing that head-butt dance so much.

CARL: I don’t think it affected my brain, but it is rather dangerous, which is why I stopped doing it. I remember we did it so often that when we got to America I thought, ‘Let’s get some crash helmets, this is hurting my head.’

MIKE (writing in diary): Didn’t see much of Liverpool. I would have liked to. The matinee was pretty crap but the late show was really good. We came on after the Specials and joined up on Madness. We made £7.

JULY 21: Electric Ballroom, London

Read more

Madness play to their biggest crowd to date – 1,500 – as they support The Specials again, along with The Selecter, at the newly soundproofed Ballroom. Ticket demand is so overwhelming that Camden High Street is practically blocked off. They join The Specials and The Selecter at the end for Long Shot Kick De Bucket. A storm of positive reviews appear in the music press.

SUGGS: Playing the Ballroom was a real step up for us. It’s not much to look at from the outside, but inside it’s a Tardis of a place. You can’t beat the atmosphere when the whole place bounces up and down as one.

CHRIS (speaking in 1979): We want people to talk about the Madness sound in years to come. We don’t like to be thought of as part of any revival ‘cos after that fashion’s dead, the groups that rely on the fashion aren’t heard of any more.

SUGGS (speaking in 1979): That’s the one thing that worries us. We could get labelled as just another ska revival band and get our own 10 minutes of fame like that. At the moment, it doesn’t matter what sort of music you play. You’re in vogue for 10 minutes and then that’s it. In the last month or so we’ve got as much publicity as some bands who have been slogging around for years. It makes you wonder if you’ll be back down there again next week.

WOODY (speaking in 1979): That’s one of the reasons that we don’t want to be labelled as a rude boy ska band. We want to get across to as many people as possible so that they can all come along and have a good time.

CHRIS (speaking in 1979): We are not Mods. We get a lot of Mods coming down to gigs, but they’re only a part of the audience; we’re not part of any movement. I’d like to think that we’re influenced by other people. We’re influenced by ska, we like a lot of Motown stuff and Kilburn and the High Roads. But I’d rather have our own sound than something that someone else has already got. One critic called us a rude boy ska band, but we don’t really want to be categorised like that.

CARL: Kids used to come up to me and say, ‘Oh, you’re Mods and skinheads.’ Who cares? I think things were more labelled than tribal in those days. It’s nice to be able to say, ‘We’re this band, we’re that band’ rather than ska.

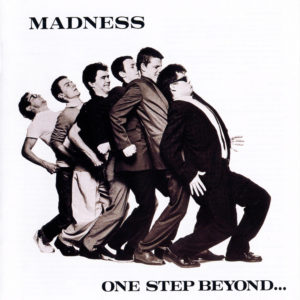

SUGGS: We were never a ska band as such, we were just influenced by ska. And we never wanted to be ‘sons of 2-Tone’ – we wanted to be Madness. We were very upfront in realising that the 2-Tone thing was going off like a packet of crackers and we were in that mode stylistically. We certainly started to put more ska into our set and we’d been very lucky to meet Jerry and that whole thing happened. Earlier than God had intended, we were suddenly the thing.

MIKE: We would have been foolish not to ride the 2-Tone wave, but it wasn’t the limit of our ambitions.

LEE: We just happened to be in the right place at the right time when it all took off.

SUGGS: We could have continued having ska hits until they came out of our ears. But we didn’t, we grew less interested in ska. And consequently, our music became less influenced by it. What changes is that you get less interested in how it outwardly appears and more interested in how inwardly you feel about it.

MIKE: We were wary of the way bands like Bad Manners were being marketed. They were a good band but we didn’t want to get lumped in with that ska bracket too.

CLIVE LANGER: To me, they weren’t like The Specials, who were an out-and-out ska band. I thought Madness were an interesting pop band, influenced by the Kilburns, 10CC and Robert Wyatt, and they just did a bit of ska. I was interested in their pop side rather then their ska side.

BEDDERS: As much as we loved ska, we were already moving away from it in 1979. We always knew we wanted to play pop and not be pigeon-holed. But I think it was led by the songs, rather than any conscious decision to leave ska behind.

CARL: The thing was, we’d always been doing pop songs. So, at the same time as we were doing One Step Beyond we were also doing the Kinks’ Slow Rock, Shoparound, and Tears of a Clown by The Miracles. We were influenced by reggae, R&B, Motown, pop and ska in equal measure. Folk just jumped on the ska angle because it was the ‘in’ thing.

BEDDERS: For example, we used to do a fantastic version of Always Something There To Remind Me. It was really good – Suggs did a great Sandy Shaw impression. For us, the ska influence had just come from older friends and brothers. It was very popular at the end of the 60s, so a lot of those records were still knocking around when we were looking for things to cover.

SUGGS: At the time it was new in England, but it was just the music we grew up with. A lot of the older kids we knew still had those records or were still into it. And, along with R&B and rock ‘n’ roll, it was easy to play and we all liked it.

JULY 28: Archway Tavern, London

Read more

Madness rehearse for next day’s show in support of The Pretenders. Afterwards, manager John Hasler brings the new single The Prince to Archway tube station for them to see for the first time.

CARL: We collected the newly pressed and bagged single of The Prince from John Hasler. I’ve got a picture of us all holding it up outside the station.

BEDDERS: We were waiting for a van in Archway because we were going off to play a gig somewhere and Hasler showed up carrying a box of records. Physically seeing your first record, right there on 2-Tone, was amazing.

LEE: I remember standing in the rain and Hasler turned up with seven discs – one for each of us. I saw the 2-Tone label with my name on it and thought, ‘I’ve made it’. It was a standout moment – and not just because ‘L. Thompson’ was written under the title. To have that in your hand there, a disc which is gonna go out, it doesn’t matter whether it gets anywhere… top of the charts, bottom of the charts: I’ve got a bunch of blokes behind me who’ve made this record. It didn’t mean anything, whether it made the charts or not. It was just to reach that point. We were a proper gang now, ready to take on the world.

SUGGS: I remember very clearly standing at the roundabout with a traffic cone on my head and The Prince in my hand. And as any working chap will tell you, that’s the only way to celebrate the release of your first single. We were all just staring at this piece of vinyl with our name on it for the first time.

CARL: I recall Hasler literally jumping for joy; it was the real deal. I’m smiling as I think of it and how thrilled we all were. Our gang, us. We had done this. We were part of 2-Tone and it felt like we were part of a movement. A counter culture, a passionate tribe. Expressing itself in sound, style and attitude. And we had plenty of that.

BEDDERS: When it was put in our hands, I remember very vividly Woody saying to me, ‘This is great. How long do you think it’s going to last? Three albums?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, three albums seems about right.’

JULY 29: The Lyceum, The Strand

Read more