1978

More gigs, more line-up changes, and the realisation that this pop star malarkey might just work.

FEBRUARY: City & East London College, Islington

Read more

The Invaders’ third gig is in Pitfield Street, with Suggs on vocals. It’s their first gig in a proper venue, but minus Carl and Lee, who have left after arguments with Barso about a lift home (Carl) and musical differences (Lee). In to replace them come Gavin Rogers (bass) and Lucinda Garland (sax). Setlist includes: Tequila / Poison Ivy / So Fine / Swan Lake.

CARL: I was just latching onto the bass when I left over something really petty. I had a falling-out with Mike because I just wanted a lift home and he used to charge me 20p for petrol.

MIKE: I was feeling quite used y’know? Everyone was like, ‘Drive me home’ and I was just the mug driving them. These may be petty things, but we didn’t communicate very well in those days. It also didn’t help that while we were rehearsing one day, Carl blew up an amp that belonged to my brother Ben. So that really finished him off as the bass player.

CARL: We didn’t talk to each other for a while, like you do when you’re teenagers.

MIKE: Me and Lee did a lot of arguing back then too – we called each other names. I was horrible and forced everybody to do things and Lee didn’t like it. But Lee never really said what he thought of me and maybe it’s his fault for not speaking up. These days he says more what he thinks. In those days he didn’t say anything and he might storm out moody and I wouldn’t know why he did it. But we never really used to have big arguments.

More changes and first song

Read more

Lucinda Garland leaves after one gig to go to uni. Meanwhile, John Hasler has written the band’s first song, Mistakes, which later appears on the B-side of One Step Beyond.

KERSTIN RODGERS: Lucinda was quite posh, I seem to remember, not really the right image for Madness.

MIKE: We were rehearsing in my bedroom at Crouch End. Hasler rushed into the other room and started scribbling down lyrics for Mistakes. A couple of minutes later he’d written these words down – I think that was the first tune we wrote. I thought, ‘If he can do it anyone can’.

CHRIS: When Hasler wrote Mistakes, it was really the breakthrough we’d been waiting for. It wasn’t brilliant, but it was the first song any of us had ever written. When we wrote that, we realised it could work. Up until then, we’d mucked about playing reggae and rock ‘n’ roll at parties.

JOHN HASLER: They were playing a two-chord vamp and I just went into the next room and wrote the lyrics. Poems, songs, the first two pages of a novel… I’d give lyrics to Mike to write the music; he’d change a couple of words, then claim he’d written the whole song!

SUGGS: I’m not being horrible but, like Mike, I thought, ‘If he can flaming well do it then I can certainly write a song.’ It just began from there – people started having the confidence to write their own songs.

MIKE: We started slowly. Like, people would come in with just a couple of chords on a piece of paper. ‘That’s not a song!’ So there was mishing and mashing.

APRIL 5: The Nightingale pub, London

Read more

The Invaders play at the Nightingale, off Park Road, but are refused further bookings after neighbours complain of noise. Now living with his parents in Luton, Lee returns for a one-off appearance, bringing with him a WEM amplifier and a sax microphone stand (which he forgets after the gig). After their show, the band use the Nightingale for rehearsals, both with and without Lee. Set includes: Tequila / Poison Ivy / So Fine / Swan Lake.

CHRIS: The Nightingale was really good… a seminal gig. Someone over the road complained about the noise, so we didn’t get any more.

MIKE: The pub was so near the house they couldn’t hear the television. But we were off – we had mastered our instruments enough to play a half-reasonable gig.

APRIL 22: Gavin Rogers's house

Read more

The Invaders perform at a birthday party for Gavin’s father. The set includes: Poison Ivy / So Fine / Swan Lake.

watch video

MIKE: I was a better musician than the others in those days. With my brothers playing the piano, I had a head start. Chris and Lee were still learning as we went along.

KERSTIN RODGERS: Mike was always playing piano – maybe 12 hours a day. He was always tinkering around. All three Barson boys were incredibly talented.

SUGGS: Mike was definitely more proficient to start with than the rest of us. I mean, some of the band just picked up their instruments and joined. Mike had a head start and was the best player – it would be fair to say that he’s one of the great musicians of his time.

CARL: He’s definitely the most talented musician in the band. Plus his single-minded determination not only started the group but drove it through many rehearsals until we became what we were. The gang turned into the band from his determination. He just said, ‘We’re gonna be a band.’

KERSTIN RODGERS: Mike was clearly the musical director, the one who created the sound. Lee, for instance, would have ideas, but Mike would have the technical ability to make those ideas concrete.

SUGGS: Mike was definitely in charge. He’d say, ‘The only other young band out there is the Bay City Rollers and they’re rubbish.’

MIKE: I didn’t want to be the leader, it was just the way it developed. I was always saying, ‘We’ve got to rehearse’ and there’d be a lot of whingeing. Me and Chris were the more serious ones. Lee, Carl and Suggs came and went: ‘I want to go to football… I want to go to the pub… don’t fancy rehearsing.’ I felt I had more understanding that you have to do a lot of rehearsing to get from A to B. And with the rest of them being carefree, someone had to push to make it happen.

LEE: Mike was really driving us hard. We were just fooling around really but Mike wanted everything to sound exactly right.

SUGGS: He would say, ‘Look, if we take this thing seriously, we could get somewhere. We’re young, we’re relatively good-looking, we’re making the sort of sound that no-one else is, but we’ve got to work hard.’ That was the bit I didn’t listen to – I wasn’t taking it seriously enough.

MIKE: I was just trying to hold it together. Some people would think they didn’t have to do anything and it would all miraculously happen at the last moment.

CHRIS: I never thought we’d get anywhere, but Mike always seemed pretty confident.

MIKE: I have no idea why I thought we could be successful. I mean, I look back now and we had nothing going for us really, except that we were young and we were an interesting bunch. I just felt sure we could be a success if we stuck at it. I was the one saying, ‘We’d better do this if we want it to happen’. I was pushing – it’s in my character.

CARL: In those early days, Mike would say, ‘Let’s go down and rehearse’ and we didn’t even know what he was talking about. We’d go down and do it, but he was the only one who saw it as work coming together. We just saw it as something to do; we didn’t really think anything would ever come of it.

MIKE: No disrespect to Carl, but I have a feeling that when he was in my bedroom playing the instruments, he was thinking, ‘What do I want to be here for?’ That was my impression of what was going on.

PAT BARSON (Mike’s mum): Mike was absolutely determined they were going to be a pop group. I said, ‘Does Lee have to be in it?’ Because he kept not turning up for rehearsals and Mike would be cross and fed up with him; moaning about him in the kitchen. I’d say, ‘Well why don’t you kick him out?’ And he said, ‘No no. He’s very important. He’s got the right image.’

A new underground rehearsal space is found.

SUGGS: We used to rehearse in various venues, one of which was a very nice church hall near Muswell Hill. We were supposed to pay 50p a week and we gave the money to Lee, but after about five weeks we got kicked out because he’d never paid the vicar.

CHRIS: Then in the middle of 1978, we found a new rehearsal room in the basement below a dentist’s surgery on Finchley Road, NW3. We had to clear away the plaster casts of teeth and bits of old drills to set up our equipment. It was our first permanent home and it was where we developed most of our first album.

SUGGS: It was the first time we had our own base where we could rehearse any time we wanted.

Suggs finds himself in the Stamford Bridge stands more often than in the rehearsal room. Out he goes.

SUGGS: The band was getting more serious and was rehearsing three evenings a week and on Saturday afternoons. But I was probably more keen on going to football than I was in music at that particular time and I was away every other weekend, watching Chelsea at home with a gang of mates. It was difficult.

CHRIS: He went to a Chelsea match instead of coming to practice with us like a good boy, so Mike chucked him out the band.

SUGGS: Rehearsals started to get a bit serious for my liking, so a couple of times I bunked off pretending to have a sore throat or something. I’d missed maybe one or two rehearsals and Mike was getting fed up. So I was in the band then very shortly afterwards I was out again.

MIKE: He kept going off to football when we were supposed to be rehearsing and obviously everyone got a bit pissed off – not just me.

SUGGS: Legend has it – and if you repeat the story often enough it becomes true – that I found out I was sacked when I was looking through Melody Maker and in the Jobs Vacant section I saw an advert: ‘Semi-professional North London band seek semi-professional singer’. They didn’t have the wherewithal to tell me face-to-face and to add insult to injury, they obviously didn’t even think I was semi-professional! I recognised Mike’s phone number at the bottom, so knew I’d been sacked. So I rang him up and he said: ‘No no no, yeah yeah yeah… sorry mate but it’s just you’re no good’. So I was out. Things could have been very different.

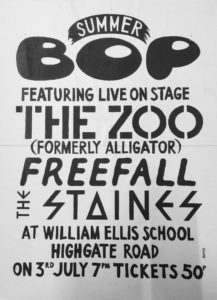

JULY 3: William Ellis Secondary School / The 3 Cs Club, Warren Street

Read more

Before the 3Cs, The Invaders play at the William Ellis summer party, alongside other bands. The gig is co-arranged by William Ellis pupil Mark Bedford, replacement bassist for Gavin Rodgers, who can’t stand the lack of organisation. Mark has experience in groups such as Bros Funk and Steel Erection, and brings along a new drummer, Garry Dovey. After a successful audition, John Hasler takes over vocals from Suggs. Chris brings along a WEM amp especially for both gigs. In the audience at the William Ellis gig with Suggs is one Daniel Woodgate. The 3Cs gig is arranged by Low Numbers vocalist Phil Payne, Chris’ brother in law. Suggs is again in the audience to encourage them. Both sets include: Giddy Up A Ding Dong / Poison Ivy / Swan Lake / So Fine / Sunshine Voice / Mistakes.

KERSTIN RODGERS: To his eternal consternation, my brother left because he thought they were going nowhere.

BEDDERS: I organised this summer bop myself, a free concert for all the kids in the school. We hired a PA and printed tickets to make it seem like a proper event. It turned out really well. A punk band called The Staines couldn’t make it so the North London Invaders stepped in. John Hasler was on vox, Garry Dovey on drums, and Lee and Woody were in the audience.

NICK WOODGATE (Woody’s brother): I was playing in The Zoo, who headlined the show. Although it’s news to me that we even had a name.

CHRIS: Suggs came along when we did those couple of gigs with Hasler singing and you could tell that he was sorry not to be in the band.

SUGGS: The gig at William Ellis was the first time I’d been in the audience watching them instead of the other way round. It was like a scene from a movie, with all these girls screaming and rushing down the front, and I was left nonchalantly at the back, smoking a fag and thinking my allegiance to Chelsea was waning. I just thought, ‘Hang on, this is all wrong. I should be up there, not down here.’ It dawned on me how stupid I’d been and how much I enjoyed being in the band. I realised I was at a crossroads and had to make a decision. Football and music were both all-encompassing but I had to give everything to one or the other and take responsibility for my fate. Up until that point it had always been a bit of a joke and I only did it for the laughs, but that was the moment when I thought, ‘This could actually become real.’

MARK BEDFORD: Born August 24 1961, London

Read more

The son of a newspaper printer, Kentish Town native Bedders is the youngest member of Madness. He’d never played reggae, so after joining, his colleagues bombard him with records to educate him.

KATHY BEDFORD (Bedders’s mum): Mark was always quite normal really. He never climbed any trees, never got into any fights…well, only once.

BEDDERS: I went to William Ellis School in Highgate Road, which was a grammar school for boys. It was very traditional, quite small – there were only 90 people in each year. You played rugby and a bit of football and the teachers wore gowns, so it was quite a proper schooling experience. The best thing about it was meeting a lot of people that I probably wouldn’t have come across before; such a wide range of people with a lot of different interests. Coming from Holloway and meeting kids who were from Hampstead opened up a whole new thing for me. A lot of them also played music, which got me into it and certainly got me into listening to different things.

KATHY BEDFORD (Bedders’s mum): Mark had always liked music. When he was five he had loads of plastic instruments – a plastic drum kit and a Beatles guitar. He was whistling at one, and when he was five his favourite record was Telstar by The Tornados.

BEDDERS: My parents and grandparents weren’t big buyers of records, but they did have things like The Beatles and stuff, like everyone did back then. The first record I can remember hearing and really liking was Telstar by The Tornadoes, when I was about five or six. I listened to the radio a lot as a kid, things like Junior Choice, which was tunes for kids. They played things like The Laughing Policeman, Right Said Fred and Sparky’s Magic Piano. The first music I ever got into seriously was Motown. That was when I was at primary school. I can remember it on the radio in the morning – Tony Blackburn was on the Radio One breakfast show and he was the champion of Motown, playing all the new stuff first. That’s really the first music I heard. Then I kind of lost interest in music until I was about 12, when someone bought me a plastic record player for my birthday and I started buying the pop songs played on the radio; the first record I ever bought was I Can See Clearly Now by Johnny Nash. I took some pocket money and got if from HMV in Holloway Road. I think I was attracted to the melody. About a year later I got my first musical instrument, a bass, so I could accompany my friend, who was a guitarist. He was having lessons and had his own guitar and said, ‘I want to form a band, can you learn the bass?’ So that’s how I got into it. I was very lucky as, like a lot of kids, my grandparents bought my first instrument for me. And my family certainly encouraged me to play. Our band was just a typical school group, doing Beatles covers and stuff – nothing special. I was influenced, indirectly, by Ian Hunter of Mott the Hoople. I’d seen them on Top of the Pops and liked their songs. The way he sang: ’And you look like a star / But you’re still on the dole’ from All The Way From Memphis was really intriguing. I found out he had a book out so I went to Compendium Books in Camden Town and bought Diary of A Rock ’n’ Roll Star. I read it and thought, ‘This is what I want to do.’ Unfortunately I had to wait for a couple of years, so I kept practising and listening to whatever took my fancy. Given my age I straddled punk, so there were key records pre and post. At school I listened to Steely Dan, Little Feat and Neil Young – After the Goldrush is still one of my favourite records. I then got into the blues, stuff from New Orleans, R&B and soul. Then once punk erupted, I was a massive Clash fan. I also couldn’t stop playing Elvis Costello’s first album. And of course, if you were a music fan listening to John Peel was compulsory. Me and a group of friends then started sneaking into pubs and listen to music. At the time it seemed that every pub in North London had a back room with a band playing in it. I soaked up a lot of musical education in the Hope & Anchor, Dingwalls and The Carnarvon Castle. Then we widened our repertoire and then started going to the Sunday concerts at The Roundhouse, which were amazing. As far as influences went, like everyone I adored Motown’s James Jamerson and David Hayes, long-time bass player with Van Morrison, was an important influence. I also took note of Bruce Thomas with Elvis Costello and Norman Watt-Roy with Ian Dury. The drummer Kieran O’Connor and pianist Diz Watson also taught me a lot. So by the time I got the call to audition for The Invaders, I’d got a fairly solid background and knew what I liked. The band had been a revolving door up until that point but had settled down a bit when I arrived, thank God. I’d been in the sixth form less than a year and was only about 17, so they were a few years older than me – early 20s. They’d just sort of got out of Mike’s living room, really. There was Mike, Chris and Lee. Mike played the piano a little bit, Lee was still struggling with his sax and Chris was still trying to untangle his fingers from the guitar strings. I dressed up especially for the audition and made a real effort, but got amazing blisters on my fingers because I had to borrow a bass for the day and it was dreadful. The strings were so far off the neck, they were almost impossible to hold down with two fingers, let alone one. I also had trouble playing reggae or ska, which I’d never done before.

CHRIS: Bedders did bluff it a bit: ‘Oh yeah, I like reggae.’

MIKE: I’m not sure he’d ever heard of it. I remember having to tell him a bit about it.

BEDDERS: I had heard ska and reggae from older kids. Because if you think about kids our age, it was all older brothers and sisters who got into that stuff when it came over in the first wave. So I would have heard it in other peoples’ houses when friends were playing their elder siblings’ record collection. But it wasn’t really my thing back then, and they’d obviously learned religiously from the records, so were very good at it. Even then they held down the offbeat and musically it was pretty good. I just remember that Chris christened me ‘Bedders’ more or less as soon as I arrived. He said, ‘Oh here’s Bedders’ which I’d never heard before in my life. It just stuck.

CHRIS: The other thing was, that rehearsal was in a really flash place because we knew this other band called Split Rivett and had borrowed their equipment. So Bedders thought he was in something really pro. He got a rude awakening later when we went back to our usual basement in Finchley Road.

BEDDERS: Suddenly I was in the middle of all these blokes who were older than me and acting like complete maniacs. It was really unnerving. The first thing that struck me was that Mike was very determined. He was single-minded. He said to me at that first rehearsal, ‘We’re gonna make records’. And there didn’t seem to be any argument about that. Suggs wore the more traditional skinhead gear – two-tone suits etc – but I wouldn’t call him a skinhead because he mixed the styles up more. Even then he had a flat-top haircut, Carl as well. When I knew them from afar, I thought it was great that they wore a mixture of 50s, 60s and 70s clothes that made their own fashion. You couldn’t really pigeonhole them. Lee, Chris and Mike’s friends had quite a different style. In London at the time there was a trend of espoused Americana, the fashions and styles of the film American Graffiti. People were wearing baseball jackets, 50s-type jackets, then some people would mix it up with 60s fashions. The Invaders were wearing 50s suits, or maybe 60s mohair suits, but with brothel creepers, y’know? Not ‘Jam’ shoes. I was struck by Lee in particular as he had that mixture of 50s, 60s and 70s; he was a real conglomeration of those decades.

MIKE: Carl used to wear American airman’s sunglasses, which I used to hate. I was more into British-style jackets, stuff like that.

BEDDERS: There were definitely two camps in the band, maybe three. Lee, Chris and Mike all knew John Hasler, who was the massive link between us all. I was at school with him, although he was a couple of years older than me, and he also knew Woody. He was a real character and a real sort-of face. He always looked amazing and used to be known as Rockin’ Billy Whizz as he had this big blond quiff, but he also looked really scary, which is funny cos he’s the sweetest person you could ever meet. I was also at school with Clive Langer, although he was also a few years older than me, so I didn’t really know him. I was also friends with Woody; not very well but I’d seen him around the area and had spoken to him before joining the band. It was another example of there being a lot of connections because everyone was hanging around in the same area around Camden, Highgate and Hampstead at that time; like Suggs and Carl being very close and living very close to one another.

A new drummer...and a new manager

Read more

The new line-up doesn’t last long, as John Hasler decides he’s not a good enough singer. Lee then literally kicks out Garry because he doesn’t like drummers. Suggs is now singer again, after persistently turning up at rehearsals. Hasler is elected manager.

CHRIS: Garry was OK – he was strong and could keep time, but it was so typical of Thommo to come back and decide to get rid of him. I don’t know what it was about but he just went for him in rehearsals.

JOHN HASLER (ex-drummer and manager): We were doing Ian Dury’s Rough Kids, which starts with a really unique drum intro. Garry couldn’t do it, but to make it worse he wasn’t really trying, and was sort of like, ‘I’ll just do my own thing.’ And so Lee lost it with him.

LEE: I was a bit drunk and wound up about something else and he was winding me up even more, so I just jumped across and had a go at him. He was a really big bloke, real meaty, and he grabbed me by the neck.

CHRIS: Because Garry was so strong he just held Thommo at arm’s length; he could have held him there all day if he wanted to. In the end Thommo wriggled free and legged it. But it meant we needed a new drummer – again.

SUGGS: Mike said, ‘We could do with you back in the band on drums cos Hasler’s auditioning for singer.’ So there I was, playing drums in Mike’s bedroom while a succession of Robert Plant lookalikes were rejected one after the other. Unsurprisingly, Hasler got the job.

CHRIS: Then Hasler went on holiday to France and I overrode Barso, went over his authority and rang Suggs and asked him if he still wanted to do it.

SUGGS: I was the only one who knew the songs, so they had me back. They were doing a gig in a shop in Hampstead and fortunately they needed me.

CHRIS: So Suggs did the gig and we thought, ‘We’ve got to have him as the singer really.’

SUGGS: It turned out that being sacked was the best thing that ever happened to me. After I came back I became much more focused and stuck to the principle that we work really hard. We had some hard times, but we stuck together.

WOODY: When Garry left the band, I got on the phone to Bedders because I really liked them and said that I’d heard they wanted me to join. He said, ‘No, I hadn’t even considered it. But you might as well come along.’ It was incredibly embarrassing.

BEDDERS: Woody rang me at home and said, ‘Are you looking for a drummer?’ And I said, ‘No, but I’ll tell the rest of them. Do you want to come along to a rehearsal?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, OK.’ I’d met him when I was 14 and he had very, very, very long hair, and had also played with him at various things in and around Camden, so I knew he was good. He’d always been ‘Woody’, ever since school days.

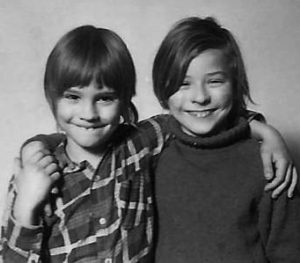

DANIEL WOODGATE: Born October 1960, London

Read more

The Invaders advertise for a new drummer, so Woody rings Bedders to ask if he can audition. Woody grew up a bohemian hippy in Camden. His father, Crispian, shot the British acting elite of the 1950s and 60s – including Roy Kinnear, Peter Cook, Albert Finney and Ian McKellen – and his work appeared in the National Portrait Gallery. Woody liked The Mahavishnu Orchestra and Steve Hillage and knew nothing about ska – he only joined The Invaders after seeing them support his brother Nick’s jazz fusion band. Before that, he worked as a sign writer and printer in the department store Whiteley’s to pay for his seven-piece Premier drum kit, bought on HP from Blanks on Kilburn High Road. After he paid it off he left the job and did building and labouring work in Earl’s Court.

WOODY: I come from a very well-off, middle-class bohemian background, although my parents split up when I was about three or four, which was a horrible experience. Strangely for the 1960s, my dad got custody of me and my brother Nick, who is 15 months younger. It was a reversal of the standard as my mum, who lived in West London, was the weekend parent. Dad then got remarried to a journalist called Celia Haddon and they bought a six-bedroomed house in Camden in 1965, in a little road called Stratford Villas. It used to be a real Greek and Irish community and the biggest shop in Camden Town was the Co-op on the High Street. There were about four down-and-outs that you used to know by name. It was a great place to live and it was great for me and Nick to have such a large house in which to grow up. Because my dad was a photographer, he was always away on shoots, so we grew up with au pair girls and nannies; we basically had no boundaries or limitations. But things could be difficult too – it’s no secret that my dad was an alcoholic.

NICK WOODGATE: Dad was pretty bohemian, so I was allowed to roam around unsupervised. I’d go to my friend’s house and we’d experiment with various pills and marijuana. I was 11 when I first took LSD. Looking back, I can see now that it was quite a sordid existence.

WOODY: Both my grandfathers had been conductors, one with the BBC in London, the other with big bands in Blackpool. My dad also earned very good money as a photographer, so I grew up with people like Albert Finney and Eric Idle coming round to our house. It wasn’t a very real world, but it was the one I grew up in. For instance, I actually met the whole Chelsea squad at the training ground in 1969 when my father took me down and after that I was hooked. It was great – I met David Webb, Peter Houseman, Ron Harris, Peter Osgood, Eddie McCreadie, Alan Hudson and Peter Bonetti – what a side! Really, when I was first introduced to Chelsea, they were the best team. I also went to see the Rolling Stones in Hyde Park. But that was about it for big gigs – I don’t really like big crowd scenes personally. Although we lived in the huge house, I still went to Haverstock – one of the area’s roughest schools – whereas Mark, who was working class, went to quite a toffish all-boys grammar school. When I first arrived at Haverstock, a teacher had been stabbed to death with a woodwork chisel. Education was whatever lesson you decided to go to. So I chose art and music. I ended up doing a lot of drumming. In the latter years, my mate and I used to go to Steve Hillage concerts, take the music teacher and get him stoned. My favourite teacher was the Spanish teacher, Dave Provis. One day he said, ‘Write some poetry about childhood’ so I went home and found this obscure Elton John record, copied the words and gave them in. All he did was write ‘Bernie Taupin’ at the bottom. He was really clued up! They’ve built flats where my old school used to be, but we had running battles with the ‘Chinks’, the ‘Pakis’ and the ‘Plugs’. ‘Plugs’ were the deaf kids. It was terrible, but this is the way kids are; they’re really cruel, they’ve no sense of political correctness. Nick and I were really close and spent every hour of every day together – he was my childhood hero because he was the clever one, the good-looking one, the one who great at sports and a brilliant musician. It was kind of annoying as he was so perfect, but we shared everything together. We loved The Beatles and used to air guitar around the front room. When Nick was about 10, dad realised he had a real talent for playing the guitar. I couldn’t play a thing, but to keep up I picked up a pair of sticks and started bashing the furniture. That morphed into taking up the drums, which seemed easier than learning a proper instrument. I got my first set when I was about 12. An old mate sold me a really ropey kit for a fiver. It was held together with Sellotape and wires and the cymbals sounded like dustbins. Back then, I collected old English coins and had a couple of beautiful half-sovereigns, so I swapped them for some proper cymbals. I used to practice on it for hours in the bedroom with Nick helping out on guitar. He was the great genius, the child prodigy, all I could do was play drums. At the time, they were building the Westway, and on the way to see my Mum we used to see this sign that said, ‘Beware: Steel erection’. We thought it was hysterical, and when we managed to cobble together a school band, that’s what we decided to call it. There was me and Nick, a very good mate of his called Johnny Croucher, and another guy called Steve Bartlett.

NICK WOODGATE: We just played drums and guitar in our bedroom, plugging in an old stereo system in to make it an amp, that sort of thing. We played every single night from the age of 10 or 11 until we were about 15. We were pretty rubbish – there was lots of widdling around on guitar by me – and also pretty loud. In fact, I never realised we were making so much racket until one day I was walking home one night and I could hear someone else playing my guitar from about 500 yards down the road. I could hear every note and all of Woody’s drums too. Our poor neighbours!

WOODY: We were quite a good little rock band; we did headbanging pop rock and covers of people like Bad Company, the Doobie Brothers and the Rolling Stones, stuff like Long Train Running, House of the Rising Sun and Jumping Jack Flash. We then progressed to classier jazz-funk, with me bashing away and also wrote a few of our own songs; there was one classic called Bartlett Bass because Steve came up with a great bass line. When you’re 14, you do such things.

NICK WOODGATE: Woody and I were pretty inseparable really. We were so close, we’d almost know what the other was thinking. Growing up, we really looked after each other’s back.

WOODY: When I left Haverstock secondary school I thought about becoming a graphic artist. I was good at art but tended to be a bit, ‘Yah, man, do your own thing’. My style was quite rebellious, a cross between surreal and fine art. I got a job at Whiteley’s in Queensway as part of the artwork team, putting adverts around the store. I was bored out of my brain but it paid for my first proper drum kit. I only had a year or so after school before I joined Madness, so I didn’t really have much of a teenage life. I’d seen them at William Ellis when Nick’s band, Animal Farm, were top of the bill – Suggs was at the same gig, but I didn’t realise that until later. We watched this wacky band called The Invaders with John Hasler on lead vocals, Garry Dovey on drums, Mark on bass, Mike on keyboards and Chris on guitar. I’m not sure if Lee was there – I can’t remember to be honest. Live, they were terrible in most respects, but there was also something really magic about them, really original. They were the worst band there, but the best and most exciting band on the bill too. People crowded the stage and I’d never seen anything so fresh and energetic. They were dreadful but brilliant – really rough around the edges. There was just something about the sound they made that was just a bit quirky and a bit cranky, but it also had something about it. I wasn’t keen on the drummer, Garry, because I thought I could do a better job, but that was me being a young egotistical teenager. But I do remember being impressed with Mark. In the space of a couple of months, he had gone from being awful to being a really good bassist. I already knew him because we used to jam together. We knew two guys, Martin and Laurie, and their house was the type of place you could set up amps and drum kits and make a right racket. Fortunately they didn’t have neighbours who complained, so that was one of the places we’d met up and Bedders would play bass and I’d bash away on the drums. He came from a world that I understood – I think we were a bit more on the same wavelength, we weren’t kind of hardened skinheads with criminal records and things like that. So when The Invaders drummer got kicked out, Mark said, ‘Well you might as well come along.’ Turning up for the audition was like entering another world. They were quite heavy, quite a moody approach to saying ‘hello’ – they were like unsociable hard nuts and a bit off-ish when I first met them. My first impression was that they were a bit dangerous. I was picked up by Mike in his van. ‘Alright mate, get ya drums, is this it?’ So we bunged them in the back and it was like, what a nice fellow! Mike doesn’t go, ‘Hello, how are you? Nice to meet you.’ He’s more like, ‘Alright’. Anyway, we got to rehearsals and Chris just looked at me, nodded, sort of went ‘Yeah’ and never spoke to me the whole session. I think Lee turned up and just stood in the corner. It was a real weird atmosphere. I thought, ‘What have I let myself in for?’

BEDDERS: I just remember Woody turned up with a massive yellow drum kit; I mean HUGE. It took him an hour-and-a-half to set it up. We were all sitting there going, ‘Oh for Chrissakes.’

SUGGS: He had about 14,000 drums and gongs and cymbals and stuff. We were just thinking, ‘What the fuck is all this?’

WOODY: Mike was pretty much as miserable as he is now. He kept going on that he’d put an advert in the Melody Maker for a drummer: ‘Well, I dunno yet mate, we gotta wait and see and, y’know, we gotta try ’em all out first. I’ve spent me money.’ He definitely wanted to hear if there were other drummers first. And then there were these rumours about my predecessor being beaten up by Lee. I’d heard about the way he’d leapt on Garry Dovey and didn’t like drummers, so I was a bit nervous about meeting him. Especially as I knew him because he went to Haverstock School – or should I say he visited Haverstock occasionally. He was one of those characters who used to appear , then you’d to see him on a shed roof, bunking over a wall. He was renowned for being a bit of a lad and when I first met him, he was a bit scary. Despite the frosty start, I realised Chris was kind of safe because he was a soul boy with loafers; a chino-fied kind of guy. Plus I knew where he lived. But the rest of it was all pretty menacing, a bit, kind of, ‘What the bloody ‘ell’s’ all this about?’ Joining them was also a revolution in my musical taste. I was into Gong, Steve Hillage, John McLaughlin, Mahavishnu, Jeff Beck, Herbie Hancock, but equally I was a kid of the Seventies so I loved Bowie, Bolan, T Rex, Roxy, Alice Cooper and used to listen to guitar bands, My dad had one of the first cassette machines and had a tape with Whole Lotta Love and Hey Joe, which was truly, truly exiting. I listened to it over and over again – I just loved the absolute pure energy. I wasn’t into soul or reggae – I loved intricate jazz fusion. I was a bedroom teenager who liked to listen to progressive rock, so I’d never actually met blokes that danced and liked to have good time that way. It was a new and incredible world for me. I’d heard of Bob Marley but I’d never really heard of Motown or Ian Dury. I was like, ‘Prince Buster? Who the hell’s he?’ I was just a boring, middle-class little fart who didn’t know anything about reggae or Blue Beat…

CHRIS: …and within three weeks he was a real skinhead, smoking 20 Number Six a day and mugging old ladies.

WOODY: Mark and I vividly remember graffiti around the Hampstead area. The one thing we always remember is seeing ‘Mr B’ and ‘Kix’ written on railway arches and we used to think, ‘How the hell did they get up there?’ This was Mike and Lee. They were quite infamous, so to find out you’re in a band with them years later – Mark and I were in awe. Then I found out that Suggs was a Chelsea supporter, and that meant we had a lot in common. When I first met him, he came across as this quite imposing skinhead and he went down to Chelsea quite a lot. In those days, I was a bit of a hippy and at first it was strange trying to relate to him but, both being Chelsea supporters gave us something to talk to each other about.

BEDDERS: He was very good, but we said to him, ‘If you want to join the band, this kit has got to go. You’ve got to have four drums and that’s it.’ And he went, ‘Yeah OK, that’s fine.’

SUGGS: The other thing he had to do was get his long hair shorn off unceremoniously.

WOODY: They thought I was a right geek, which I was really; long hair and Kickers and dungarees. It was like, ‘Get your hair cut and buy yourself a suit mate.’ I found my first two-tone suit, which was actually a three-tone suit, in an Oxfam shop for £2; it just about fitted me. I went with Bedders, who had been put in charge of sorting me out.

BEDDERS: There was a shop on Camden High Street that had second hand suits, and a few of us took him in there and got him kitted out.

WOODY: So I got my hair cut and got myself a decent suit. But I was still the same person underneath.

SUGGS: People had come and gone, but when Woody and Bedders arrived – almost as a unit – all of a sudden you could hear we had a band, rather than just a load of mates mucking about in a basement somewhere. They were good and it sort of solidified the whole thing.

MIKE: That’s definitely true; Woody and Bedders were almost like professional session men compared to some of us.

WOODY: To be honest, I didn’t think much about what they played. I was really vagued off listening to Weather Report, Mahavishnu Orchestra and Eno back then. I was a bit of a dreamer and still am. I’d never played reggae in my life but there was nothing better to do, to be honest. At that time I was considering living in Ireland. I felt disillusioned with myself and had no idea what I was doing.

The magnificent six

Read more

After Woody’s successful audition, The Invaders are now a six-piece band: Mike (piano), Chris (guitar), Bedders (bass), Woody (drums), Lee (sax) and Suggs (vocals), with Carl still on the fringes as unofficial mascot-come-dancer. The band start rehearsing and slowly developing their own sound.

MIKE: Once all the instruments were taken that was it – no one else could be in the band.

SUGGS: At first we used to feel really embarrassed because we were playing old fogies’ music. It was really hard for us. We were playing a mixture of Blue Beat, ska and pop – right in the middle of the punk and disco era. It was too slow for the punks, not groovy enough for the disco chaps. But we just kept on going because that was what we were into.

CARL: We were going against the grain, definitely. We were different to everyone else around, wearing baseball jackets and mixing up different cultures. It was exciting. We were developing our own thing – not that we were conscious of it at the time. We had a different image but we didn’t think of ska as some great new thing at that point, to be honest. We just played R’n’B and ska because it was easy – 12-bar stuff.

MIKE: R’n’B and rock ‘n’ roll is easy music to start with when you’re beginning a band. Most groups begin with Johnny B Goode, but most of them don’t work those songs out right – you’ve got to get the rhythm correct to do them properly.

CHRIS: We never consciously said, ‘We’re a ska band.’ We never put those limits on what we were doing. That’s musical suicide, sooner or later. Other people lumped us into that but we didn’t mind; we knew what we could do.

SUGGS: It was trying to find a way of expressing ourselves that wasn’t just what everyone else was doing. You had punk, but if you didn’t want to go into that slipstream, the only other thing to do was find some obscure music that no one else was interested in. So it was ska. Nowadays, retro is so… retro. Back then, it was a new thing, finding a Coasters album or some old songs that nobody had heard for years. To collect Prince Buster, you really had to search the records out. People would be really excited if they found a record. Now, it’s an industry. But back then enthusiasts started to appear out of the woodwork; rediscovering things that had been forgotten. Having a crop and wearing winklepickers and blue suede shoes made you a monster from out of space.

WOODY: Most of the band were listening to all kinds of stuff. They would collect obscure records, and a lot of them were old Blue Beat records with Prince Buster on, Skatalites … just loads, loads of obscure stuff most of which I hadn’t heard of until I met them and they opened my eyes up to it. It was kind of exciting it was really good stuff. My mum liked The Kinks more than I did, but they grew on me massively when I was exposed to them by the band.

SUGGS: You meet Americans who say, ‘How did you get into that kind of music?’ But the thing was, when you were walking around the streets of London, that music was coming out of doorways. Notting Hill Carnival and all that was part of our lives. It was just like any other kind of pop music to us. So we had The Beatles, but we also had Desmond Dekker and Toots and the Maytals.

WOODY: It wasn’t just ska though – we listened to everything. We were influenced by Roxy Music, The Kinks, blah blah blah, you name it. We all had quite eclectic tastes – but I suppose my musical tastes were more diverse that the rest of the band in those days.

SUGGS: Ian Dury, Ray Davies and ska and reggae were our most obvious inspirations, but other people in the band were inspired by Pink Floyd. So there were strange offshoots that you wouldn’t necessarily see straight away in Madness. But I think that gave us more of our rich texture.

WOODY: Because we grew up in the 70s, there was a wonderful mix of music and I think we pinched enough stuff from all of those influences for people to relate to.

BEDDERS: Definitely. If you got us all together and we got our records out, there would be a massive cross-section of stuff, from traditional jazz all the way through to experimental and electronic music, reggae and Motown – it was fantastic that there was such a breadth of influences.

MIKE: The only thing was, nobody in the group liked punk much, except for Bedders – he was a big Clash fan.

BEDDERS: The Clash were inspirational; we’d see them on the street in Camden and they rehearsed in Chalk Farm. It was absolutely fantastic. I used to go and see them a lot; they were a massive band for the way they mixed things up – and the reggae aspect, obviously, which was a really good thing, that cross of cultures that they were trying to do.

MIKE: One time we were rehearsing in Muswell Hill and Hasler brought along a copy of White Man In Hammersmith Palais by The Clash for a bit of inspiration, cos we were doing that sort of thing. We even did a reggae version of Touch Me In The Morning by Diana Ross.

SUGGS: A lot of our early set came from Lee and his big record collection. I’d also still go to the market and buy these old records that were just lying around. I just liked the way they sounded, like they were recorded in toilets, all out of tune, and the words were funny. We were really just playing it, ’cause no one else was, along with old rock ‘n’ roll standards. There were a few jukeboxes in some of the pubs that played some of those old records, plus because of the influx of people from Jamaica, you’d hear the more popular reggae records on the radio. Those records had always been there or thereabouts – it was kind of hanging in the air. You’d also hear ska at funfairs, where all the music was 10 or 15 years out of date. Although it was the 70s they were still playing some of that Prince Buster stuff from 1964 and 1965 because they couldn’t be bothered to buy any new records. And then at the youth club there’d be a pile of scratchy old records that would have been forgotten about, washed away by the tsunami of glam rock. Ian Dury was doing his own bits of ska and reggae with the Kilburns, so that fed into what we were doing too. So we really liked the music of Prince Buster and all that, we really liked dancing music, and we really liked pop music. We liked a bit of everything really, so we mixed it all up together.

WOODY: We just kind of liked the offbeat rhythms of the ska and other jaunty rhythms of Motown and Ian Dury and we just mashed it all up.

SUGGS: Mythologically, it was easy to start doing ska music because there was an emphasis on the off-beat. But often what’s good about English bands, particularly when they’re young and not as good as they become as musicians, is that you take a form of music and you get it slightly wrong. So we put it all a bit on the four-four and took a load of the swing out of it and did a bit more bashing and banging. We were just kids having fun.

WOODY: We tried desperately hard to copy these old songs but they never sounded anything like them. We weren’t the greatest of musicians – in fact we were atrociously bad. The way we played ska was so friggin’ useless. I mean, it wasn’t really ska at all. It was nothing more intellectual than what we were doing at the time. It was just a case of seven individuals desperately trying to play something and ska just happened to be relatively easy to pick up.

SUGGS: Ska was still a great way of learning to play. It was a rhythm and would get everybody going. Even people who’d never seen you before would start dancing because it was such an infectious rhythm. Also it didn’t need too many chords and didn’t have to be too complicated – we could squash songs through and they’d come out the other side. You’re always gonna get more life out of people if you’re playing something with a little bit of go in it.

WOODY: In those early days we had a rule of thumb that if you can’t dance to it, let’s not do it. The initial drive was ‘it’s got to be interesting’ but the main thing was ‘it’s got to be exciting enough to be danceable’. I think that was the main driver behind the band, especially back then. Obviously it changed because you can’t keep bringing out songs that people dance to.

SUGGS: When we got playing and made everything a bit faster and bit wilder, we realised we had something that had the same energy as punk but you could do more than just jumping up and down; you could jump from side to side as well. Then when we started playing live, we realised the more we played that type of music, the more it got the crowd going, even though it wasn’t in fashion. No one else was doing it at that time, but it really worked live.

WOODY: People thought we were this genius new thing but we were still just trying to play our instruments.

CHRIS: To tell the truth, I never thought we really played that kind of music brilliantly compared to a lot of other bands.

SUGGS: We were just all kind of leaders of our own little gangs of people in and around the same area of Kentish Town and Hampstead. And by some natural filtering, we all ended up in this room together playing instruments. Most of it was just smoking fags and looking at each others’ trousers. Which was a very important part of growing up, of course. But we rehearsed a lot as well. Among our contemporaries, everybody was starting a band, everyone had a Jack Kerouac book and a saxophone – but they didn’t actually play it, or read the book. We did both. I certainly didn’t do much at school. Most of the band didn’t. But vocabulary was something we all shared, and an interest in films, books and even plays. One of the big things, for us, was when Max Wall appeared on Play For Today doing Krapp’s Last Tape. We were all Max Wall fans, from his visual comedy. And Samuel Beckett seemed to us perfectly relevant, just one down from Tommy Cooper, really – all about the absurdity, the repetition of everyday life. So there were things of that nature going through the band, for sure. Although we weren’t really conscious of them, at the time.

NOVEMBER 9: Blind Alley Factory, London

Read more

Supported by The Spotty Dogs, The Invaders, minus Lee, perform at a birthday party for the director of the Blind Alley in Camden, where Mark is taking a screen printing apprenticeship. When New Song – later to be My Girl – debuts with Barso on vocals, someone shouts from the crowd, ‘Where’s the sax player?’ The culprit is Lee himself, who rejoins by the end of the year. Set includes: New Song / Swan Lake / Sunshine Voice / Mistakes.

BEDDERS: We were playing and I could hear some sort of shouting coming from the back of the hall. This guy was yelling, ‘Where’s the sax player? Where’s the sax player?’ Not knowing the band very well at this point, I wondered what was going on. And of course it was Lee, who had showed up at the gig just to heckle. That was kind of my first meeting with him.

LEE: The problem was, I was in and out of the group like a yo-yo because I was living in Luton and it was difficult to get to rehearsals. The others were taking it pretty seriously but I was finding it difficult because of the situation at home.

BEDDERS: Lee would just flit in and out. He would maybe appear at a rehearsal occasionally, play a bit and then disappear again.

LEE: I used to spend a lot of time practising at home – I used to go out the back of the house into the cornfield with a blanket and and a packed lunch and make a right racket; just me, a tape recorder, Ray Charles and Fats Domino, blowing across the fields. It was quite a nice period when I was just learning the basics, rock ‘n’ roll riffs and such like. I was also in a band called Beatty, doing Dylan covers, which was good practice. But I couldn’t handle the music they were playing. Then I was in another band called Gilt Edge – a Springsteen/Dylan sort of thing. But even when I wasn’t in The Invaders I kept in close touch; I always felt that when the time was right they’d ask me… they knew the problems.

MIKE: So we’d done some gigs and we were starting to get somewhere. We were still pretty basic – not good but also not bad if you know what I mean?

CARL: Mike and Bedders were probably the best technical musicians back then. But people slowly began to develop.

WOODY: The biggest problem I had was that the music was a complete change of style to anything I’d played before. I was used to rock and jazz-funk, so it took some time to get used to. When I first joined, I’d fill the gaps with triplets on the bass drum and a fancy roll every other fucking bar. Mike used to get frustrated, kick me off the drum kit and try to play what he thought I should play. He went, ‘Can you stop doing all those rolls? It’s like this: ‘Boof, smack, boof, smack.’ I was like, ‘What, all the way through?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah.’ They wanted me to stop being so technical and play in a completely different, much more simple style, so I had to strip it back and start all over again. But I became more efficient and later I appreciated that simpler style of drumming because it allows the music to breathe.

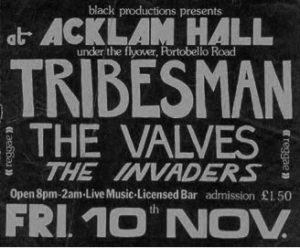

NOVEMBER 10: Middlesex Poly / Acklam Hall

Read more

John Hasler gets The Invaders two gigs on the same night – at Middlesex Poly and Acklam Hall. The Acklam Hall gig sees them opening for reggae band The Tribesmen and punk group The Valves. Two more songs, both written by Suggs, are added to the set: I Lost My Head and In The Middle Of the Night, the story of a knicker thief called George. Mike has also written another new song, Grey Day, played in a similar arrangement to Roxy Music’s Bogus Man. Carl has returned to the group as nutty compere, offering various shouts and fancy footwork. Major trouble erupts after the Acklam gig, and the band are lucky to get out alive, no thanks to the local skinhead firm but helped by Carl and future crew members Chalky and Ian Tokins, AKA Toks. After the riot, The Invaders play a dissatisfying show at Middlesex Poly, where members of the student union pull the band off stage one by one for exceeding the time limit (Chalky and Toks put them back). Si Birdsall’s brother Jesse damages the toilets and The Invaders are held responsible. Both sets include: Grey Day / Swan Lake / In The Middle Of The Night / Madness.

CHRIS: I went to the toilet after the Acklam gig and there was this bloke and I thought he was a mate of Suggs’s so I said hello. He started having a go and I was thinking, ‘Where’s Carl? Where’s Carl?’

SUGGS: Then someone burst into our dressing room with an iron bar…

CARL: …and I was on speed and we had a big fight in the toilets.

WOODY: It was horrendous – like another world. I came from a hippy-dippy middle-class background so it was a baptism by fire.

CHRIS: We were pushing our vans to get them started and get away and one of the vans backfired. They thought we had a gun. Someone shouted, ‘They’ve got a shooter’. Funny now but at the time…

CARL: The band drove off and the police escorted the rest of us through 40 of these Ladbroke Grove skinheads who wanted to do us.

SUGGS: Going to someone else’s an area with loads of your mates was taken as a threat. People would prepare for you to come and give you a welcoming committee.

CARL: We did nearly two years of youth clubs, pubs and rented vans and all that stuff; the traditional paying your dues, playing in shit holes and being threatened by people from different cities.

The band continue to refine their sound

CHRIS: It still took a bit of time until we actually became Madness. But by that time we’d stopped doing all the rock ’n’ roll songs and started writing our own – which was important. It meant we slowly started to get this kind of weird little thing going.

MIKE: I suppose when one person starts writing, then everyone else starts thinking, ‘Well I can do that too.’ So before you knew it, we were all writing songs.

CHRIS: We used to go to rehearsals and I’d say, ‘I’ve got these chords and they go like this.’ So we’d start playing, Bedders would do a bassline and we’d get it going. And then we would often get a cassette machine, record the songs and then people like Lee or Suggs would take them home and come up with lyrics.

MIKE: I remember being quite confident that the band could be a success, whereas some of the rest of them weren’t quite sure what was the point of doing it and whether it was just a waste of time.

WOODY: We were rehearsing, playing gigs, doing alright but nothing more. I didn’t know if it was something I really wanted to do, so one day, after a typically untogether rehearsal, I aired it to the rest of the band and it emerged that everyone had the same question. Everyone sat down and expressed a similar feeling, how they’d all wanted to leave. It was a great relief – it brought a unity to us. It was still Mike who was the driving force, saying, ‘Don’t think like that, we’re going for the top. Let’s do what we want.’ From then on, we rehearsed like mad, playing and playing until we got the songs right. And a year later we didn’t even have time to think.

MIKE: None of them, to an extent, believed there was much point in it. I suppose I had quite a lot of conviction that we could do something. You’ve got to rehearse if you want to be able to play.

WOODY: We were still a bit flaky but Mike was the one who pulled us all together. He was the one who had the dream and it was like, ‘It will be fulfilled.’ He really led people by the nose; if you didn’t fall into line, he would be the one who would get really pissed off.

BEDDERS: He was very dogged and kept everyone going in those early days . He made us all rehearse and it was his determined nature that kept us plugging away.

WOODY: Mike is dogmatic to the nth degree; I mean he can’t turn up on time to anything, but he’s a very determined individual. In those early days he would insist on more rehearsals and would go over and over and over songs until we got them right. He was the driving force behind what little discipline we had. In turn, Bedders and I would work tirelessly on the rhythm section, trying to get the notes right and make things tighter.

CARL: For me, there was no real driving ambition; I think I just felt happy being in and out of the band.

WOODY: We just did what we could, which at that stage, that wasn’t much. But what we did have was a regime of rehearsals – we didn’t want to do any gigs until we were ready.

NICK WOODGATE: The one thing they did have, even in those early days, was good organisation in the rehearsal room; they’d make a mistake and talk about it and redo it and wouldn’t make that same mistake again.

BEDDERS: Like any group we did a lot of covers and learned a lot of old reggae songs. But the few things we had written ourselves sounded good. We started to hear them gel, then others came along and it all felt right. I thought, ‘Oh, we might be onto something here.’ They actually sounded quite good and our first few attempts really weren’t that bad.

MIKE: I suddenly thought, ‘If you can play anything, you can write anything.’ If there had been a great songwriter in the band, a Ray Davies, then I probably wouldn’t have written a song because of feeling inhibited, trying to compete. But slowly we started working out that we could write songs too. And why not? If the punks could do it, so could we. I thought we couldn’t miss as we had a couple of elements that no one else had at that time. One was that we were under 65 and in that period it was the dinosaur period, whereas we were just a bunch of kids so I thought it was one of our cards in our hand.

SUGGS: We had our own scene, no name, no time. It went from Fats Domino to Gary Glitter to Roxy Music to Prince Buster. What was important to me was impressing this lot, not the outside world. We were from working class backgrounds but had aspirations to do something other than steal and run around the streets causing trouble. That’s why we’d started the band – for something to do.

KERSTIN RODGERS: The big rivalry was Lee and Mike, because they knew each other the longest. They were constantly at loggerheads – and Carl too – competing all the time. Suggs was the leader by virtue of being the singer but not on a musical level. With all these tempers and egos, you needed calm people, and that was Mark, Chris and Woody. Chris was a mediator, quite kind. Mark and Woody were younger, less competitive than the others; they brought a stabilising effect. They weren’t constantly challenging for the top spot. It’s like a family – you might get terrible sibling rivalry between the oldest then there’s a gap and the younger ones have a different relationship. Even Suggs, who’d joined later, didn’t quite have that problem; he was very genial and didn’t have confrontations.

SUGGS: We were so skint, we had no money for clothes. I had this green Tonic suit which was too baggy and made me look a bit portly. I used to roll the waistband over, which amused Chris no end. We also used to meet up on the bus because we lived pretty much on the No 29 bus route. So we’d synchronise our watches and catch it in order along the route; most of our first two albums were written travelling around like that. And if we weren’t on the bus, Lee and Mike used to ferry us around in these rusty old ex-GPO Morris Minor vans.

MIKE: I had this old Morris Minor van, then Lee said, ‘Someone’s selling another one’ so suddenly we had two . I think it was a hundred quid – everything was a hundred quid in those days – and I’d never had my own car before so that was sort of exciting.

CHRIS: When Lee got that second van, I thought, ‘We’ve really made it.’ All the gear went in one van and we went in another.

BEDDERS: Lee drove the yellow one and Mike the white one.

LEE: They were fantastic motors – went on forever on one tank of petrol. Although you had to literally put your feet through the bottom of the floor to get any speed out of them.

SUGGS: We put all the gear in the back when we were gardening, then at night, if we had a gig, you could put all the amps and the crap in the back. The worst bit was that they stank of petrol, so if you were in the back you came out stinking, which wasn’t the most alluring thing where girls were concerned.

BEDDERS: My first initiation with Lee was when we were rehearsing over at Finchley Road. Afterwards, he said, ‘I’ll give you a lift back into Hampstead and you can get a train home.’ And he took me on this death-defying, frightening ride. I don’t know what speed it was because I was almost in tears. I think that was my, ‘Pleased to meet you.’ I think he wanted to see if he could get a reaction out of me.

LEE: I once went from London to Great Yarmouth with my mum’s tights wrapped round the accelerator cable. Alright, so we had to go round the corners at 40mph, but you just whacked it into neutral and then back in again.

MIKE: I had a little hand-made speaker behind my head in mine, and a cassette player that I played as I drove around. At that time, I had a delivery job and was mainly delivering to ad agencies in the West End. Sometimes it was a bit more exotic and you’d have to go out to Mitcham or somewhere and try not to get lost.

LEE: Those motors really got us from A to B in the early days – if it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t be here now.

BEDDERS: Instead of going in the vans, Woody would sometimes take me to rehearsals on the back of his motorbike. It was free, but it was also really hairy; he used to weave in and out of traffic and on a few occasions we got very close to cars.

SUGGS: I don’t remember ever thinking about whether any of it was going to last; I didn’t have a clue and wasn’t taking it the slightest bit serious. I just thought it was a laugh and just something to do – hanging out with pretty cool geezers. The idea that I could make a career out of it was beyond comprehension.