1987-1991

Side projects, fresh starts and new careers are tried – and rejected – as life proves strange for our ex-Nutters.

1987

WOODY: Everyone looked around and thought, ‘Well, where now?’ What are you expected to do when you’ve been in one of the biggest bands in Britain? I was 25 and my career was over – and I hadn’t even started my life! It was a dodgy period because I honestly didn’t know where I was going. There were some dire days and I remember thinking, ‘What am I gonna do?’ Drumming was all I knew.

BEDDERS: I think it affected everyone in different ways. I felt very flat for about a year; it took me about 18 months to start functioning properly again. From 17 till I was 25 we’d worked solidly, so it took me that 18 months to feel like I was ready to do other stuff.

CHRIS: I went through a period of saying I was ex-Madness, but you’re not; you never are, until the day you die.

SUGGS: I was 25 and had done everything one is supposed to do in one’s lifetime and I didn’t know what to do next. In a way, it came as a great relief because you do have to go out there in the world on your own and find out for yourself what goes on in the real world outside the castle walls.

LEE: These were the wilderness years where I became a mountain bike shop owner, a gardener, a painter and decorater, a fly poster, a dustman, a drunk, a manic depressive and typical loser of the highest degree. It still spurs me on now.

WOODY: It was nerve-wracking. It was a bit like floundering in the deep end of a pool; not knowing what you’re gonna do with your life. I did think about getting involved in the record business in some way. But that’s not me.

CARL: The good thing about Madness was when you were weak, you had six other people to help you through your weakness and when you were strong, you had six other people to magnify your strength. And not having that was like coming out of a marriage, where you realise how much a woman did for you in your life, and how much you’re going to have to do for yourself and how much you’re going to have to learn about the things you didn’t do for yourself.

SUGGS: I actually became a bit paranoid. Our songs had been about everyday life, but where was mine? I had friends I hadn’t spoken to in years. Two of my best mates had worked for Madness — they started off in the van with us and they’d unload the gear. But as the entourage grew, they became employees No.400 and 451. The sadness that stemmed from that was horrible.

MARCH: Suggs, Carl, Lee and Chris re-group

Read more

The quartet start working on a new project, using leftover Madness songs, drum machines and a few guest musicians.

CARL: We allowed ourselves a couple of months to think about it, but we got so bored that we decided to get back together again.

BEDDERS: Lee, Chris, Carl and Suggs had said they wanted to make another record because when we broke up, we had a whole album worth of tracks demoed, so there were still some good songs knocking around. Perfect Place was a real favourite of mine. We did it with a drum machine on the Red Wedge tour without Woody and Mike and it was quite close to something like Yesterday’s Men. It did get recorded but was never used on any album, I don’t know why. In the end there were about 16 songs in various states that were to be recorded for the follow-up to Mad Not Mad, but of course things then fell apart. As it turned out, some were used on the subsequent The Madness album in different forms with different titles.

CHRIS: Gabriel’s Horn, Be Good Boy, Song In Red and 11th Hour had already been recorded with Mark and Woody playing on them. I thought they were really good versions, but we re-recorded them for The Madness. I dunno why – I think we just wanted to make a statement about making a new start. Whatever that meant.

WOODY: I think the four of them genuinely didn’t know what they were going to do and out of insecurity just stuck together. For me, it was a bit sad really. I can look back now and be objective as I know the four other members needed to do it just to get it off their chest. But it’s still a little sore in my side.

BEDDERS: For me, it wasn’t that bad because by that time I was so tired and fed up with the whole thing I just wanted to look ahead and do other things and forget music for a while, which is why I decided to go back and retrain as a graphic designer.

SUGGS: It was a long process of inner turmoil. I can remember us four looking at each other and asking each other if we wanted to carry on. It would have been easy for us all to go our separate ways but if I hadn’t thought there was something great about the band, I wouldn’t have been in it. None of it was planned, it just kind of happened.

CHRIS: We were still pretty depressed, but we decided to carry on and started writing furiously, Carl especially.

JEREMY LASCELLES (Virgin records): Carl was the most prolific, the strongest force creatively. He was coming up with a lot of interesting ideas. They were venturing into the unknown and trying to re-group. Part of me felt it was an exciting time for them to reinvent themselves, come up with a new direction and not be so fettered by their past. I relished the opportunity of working with them, trying to find that new direction.

LEE: Around the time we went over to see Barso in Amsterdam to ask if he fancied getting off his arse. But it was wrong timing and all I got was stoned on his wife’s cakes.

JEREMY LASCELLES: They’d had such an unblemished career up to that point when things went bumpy. It’s not the most unusual thing to happen when people have been together in close proximity for a long period, starting when they were really young. People grow up and start to diversify.

CARL (speaking in 1987): It might seem strange that we’re still together after we told the world that we were splitting up, but to us it’s a perfectly natural progression. It was final in the sense that things wouldn’t go on the way they were with the people who were there at the time.

SUGGS (speaking in 1987): It’s hard to look back on the past objectively. The past always seems more enjoyable than the present, so you don’t tend to look back on people individually, you just look back on times and we had some fucking great times. But I don’t look back on them with regret, I think you just look back on it as times that will never be the same again.

CARL: We allowed ourselves a couple of months to think about it, but we got so bored that we decided to get back together again.

BEDDERS: Lee, Chris, Carl and Suggs had said they wanted to make another record because when we broke up, we had a whole album worth of tracks demoed, so there were still some good songs knocking around. Perfect Place was a real favourite of mine. We did it with a drum machine on the Red Wedge tour without Woody and Mike and it was quite close to something like Yesterday’s Men. It did get recorded but was never used on any album, I don’t know why. In the end there were about 16 songs in various states that were to be recorded for the follow-up to Mad Not Mad, but of course things then fell apart. As it turned out, some were used on the subsequent The Madness album in different forms with different titles.

CHRIS: Gabriel’s Horn, Be Good Boy, Song In Red and 11th Hour had already been recorded with Mark and Woody playing on them. I thought they were really good versions, but we re-recorded them for The Madness. I dunno why – I think we just wanted to make a statement about making a new start. Whatever that meant.

WOODY: I think the four of them genuinely didn’t know what they were going to do and out of insecurity just stuck together. For me, it was a bit sad really. I can look back now and be objective as I know the four other members needed to do it just to get it off their chest. But it’s still a little sore in my side.

SUGGS: It was a long process of inner turmoil. I can remember us four looking at each other and asking each other if we wanted to carry on. It would have been easy for us all to go our separate ways but if I hadn’t thought there was something great about the band, I wouldn’t have been in it. None of it was planned, it just kind of happened.

CHRIS: We were still pretty depressed, but we decided to carry on and started writing furiously, Carl especially.

JEREMY LASCELLES (Virgin records): Carl was the most prolific, the strongest force creatively. He was coming up with a lot of interesting ideas. They were venturing into the unknown and trying to re-group. Part of me felt it was an exciting time for them to reinvent themselves, come up with a new direction and not be so fettered by their past. I relished the opportunity of working with them, trying to find that new direction.

LEE: Around the time we went over to see Barso in Amsterdam to ask if he fancied getting off his arse. But it was wrong timing and all I got was stoned on his wife’s cakes.

JEREMY LASCELLES: They’d had such an unblemished career up to that point when things went bumpy. It’s not the most unusual thing to happen when people have been together in close proximity for a long period, starting when they were really young. People grow up and start to diversify.

CARL (speaking in 1987): It might seem strange that we’re still together after we told the world that we were splitting up, but to us it’s a perfectly natural progression. It was final in the sense that things wouldn’t go on the way they were with the people who were there at the time.

SUGGS (speaking in 1987): It’s hard to look back on the past objectively. The past always seems more enjoyable than the present, so you don’t tend to look back on people individually, you just look back on times and we had some fucking great times. But I don’t look back on them with regret, I think you just look back on it as times that will never be the same again.

Woody and Bedders join Voice of the Beehive

Read more

The Madness rhythm section get a new job with the Anglo-American pop band, formed in London the year before by Californian sisters Tracey Bryn and Melissa Brooke Belland, and British musicians Mike Jones and Martin Brett.

WOODY: I came in to help them out in the early stages because I didn’t know what I wanted to do after Madness. Dave Balfe, who’d set up Food Records, had a demo from Tracy, Melissa and Mike, but they had no rhythm section, so he just went to me and Bedders, ‘Do you fancy coming in?’ So we met them and they were really bubbly and fun and the songs were great. And they needed old fart boring musos like us to come in and nail the backing tracks, which we did.

BEDDERS: Woody had met them and said they had really good songs, so he asked me to come aboard and help out. I was never gonna be there for very long; I always made it clear that I would play for a bit and then they should get in a proper bass player. But it was exciting while it lasted because with Madness, we’d been making records for a while and had all that success and so on, and suddenly I was going back to the point where a band was just about to get signed and come through.

WOODY: We did a little EP that went down really well, and then we started to do some gigs. It was really exciting and I was able to go back to my roots as all the bands I used to love were proper guitar bands – it was right up my street.

BEDDERS: We played to quite small crowds at first and then it just grew and grew and grew, and the crowds and the buzz got bigger, which was great to be part of. Woody and I always say it got our excitement back for music again after becoming jaded through years of touring and touring and touring. I remember one thing that was funny was that they never wanted to play Don’t Call Me Baby live; me and Woody would be saying, ‘But it’s a hit! It’s a hit!’ and they would say, ‘Oh no, we don’t want to do that one.’ Luckily, they relented eventually.

WOODY: The onlt thing was, some of the time I wasn’t getting paid, so my wife at the time had to go out and do courier work on a pushbike. It was only for a couple of months, but we were struggling until they came through with the money.

MARTIN BRETT (Voice of the Beehive): I think Woody may have had a point to prove to the other guys in Madness. He went on to have seven Top 20 hits with Voice Of The Beehive which, after being sacked from Madness, must have been quite satisfying.

TRACEY BELLAND (Voice of the Beehive): Woody was a huge part of the band and because of his past, he brought many Madness fans to our gigs who might otherwise not have thought about us.

WOODY: I cannot big them up enough; it was just a wonderful part of my life and I had a blast. They were very good to me and I ended up having seven good years with them. I’m really glad I did it because I had a whale of a time touring the world and going to America more times than I’d ever been with Madness. It was good tunes, good fun, some brilliant gigs and totally different and refreshing to Madness – although at some gigs, I still had idiots shouting, ‘ONE STEP BEYOND!’

SUGGS (speaking in 1987): Woody is doing really well. I think it’s good that he’s getting on and doing something. If you don’t get on and do something you spend too much time thinking about what it should be. I can always remember when we started; half the reason we were successful was because we just kept going, the singles kept coming out and we just kept going and going.

LATE 1987: Bedders flies the Beehive

Read more

Throughout 1987, Voice of the Beehive build up a live reputation, but Mark leaves to pursue his dream of composing film scores. He also ends up on a typography course and records some demos for BUtterfield 8 with sax player Terry Edwards, whose former band The Higsons released two singles on 2-Tone.

BEDDERS: I only played with Beehive for the sole purpose of them getting a deal – it was understood that I was always only going to do the first little bit because I didn’t want to get into anything for a while; I wanted a rest basically. I didn’t want to go off touring again, I wanted to do something I’d wanted to do years before. So I ended up going back to art college, at the London College of Printing at the Elephant & Castle. I had a couple of years there and really enjoyed it. I was doing the odd musical thing here and there, including BUtterfield 8, but not very much.

TERRY EDWARDS (BUtterfield 8): I was anxious about asking an excellent bass player from a famous band to play some of my tunes for a weekly wage of absolutely nothing, but I think it was obvious from the start that we were like-minded.

ROGER BEAUJOLAIS (BUtterfield 8 vibraphone player): I was surprised to find how much Mark just wasn’t bothered about the music business and had made a decision to get out of it. He told me that Madness deflected him from what he really wanted to do, which was to be a graphic designer. He’d joined his mates’ band at school not expecting it to be a success and a few years later he realised he was doing something that he didn’t really want to do. He loved music but I think there were limitations in the band. So he was reassessing his life and making plans to do what he’d thought he was going to do before being massively sidetracked. He’s a really nice bloke and good company. He didn’t have a huge ego and if you didn’t know he’d been in a really popular band, you would never have guessed. Compared to a lot of other successful people in the pop world, he was incredibly balanced and a lot less screwed up.

NOVEMBER: Suggs calls Bruno Brooks's Radio One show to ask listeners to come up with ideas for a new name for their band.

CHRIS: The only problem was a name for our new endeavour – we just couldn’t decide what to call ourselves.

JEREMY LASCELLES: They’d decided it was time to shake off the mantle of the Nutty Boys, which was why we all agreed a new name was a good idea. We went through probably a hundred different names. None of them lasted.

SUGGS: We knew we could keep the name if we wanted, but we just had the impression that we were gonna come out under a new name. So we spent a year thinking of this name, that name….

CARL: We’d go out for a drink and go, ‘Let’s call ourselves Madness! Yeah!’

SUGGS: Yeah! And then the next night we’d go out and we’d go, ‘Nah, we gotta do something different.’ What were those names again? Wasp Factory, Earthmen, The One… Chris wanted More.

CARL: And we said, ‘That’s like cigarettes you dickhead!’ And he said, ‘Yeah, but when we come out on stage they’ll be going, ‘More, More!’ ’

CHRIS: The Wasp Factory was a book we all liked, but there was already a group with that name, so we got a bit desperate.

JEREMY LASCELLES: It was a tortuous, prolonged debate and ended up with a not very imaginative solution.

CHRIS: In the end, Suggs suggested The Madness, which we stuck with, as no-one had any other bright ideas.

WOODY: Mark and I had been a bit concerned that the name ‘Madness’ shouldn’t be used for any future modern projects, for quality control. So when they re-emerged as The Madness I thought it was a cop-out – a complete cop-out. I was hurt but I didn’t feel betrayed, just disappointed.

SUGGS (speaking in 1987): It isn’t about money. I mean, we’d have probably had more promotional clout if we’d come out under a new name. People hardly go out and buy the record just because it’s by Madness. Anyway, all bands’ names have ‘The’ on the front.

CARL (speaking in 1987): We used to call ourselves The Madness two years before the split, because of The Specials. And by putting ‘The’ on it, it now means we don’t have to play One Step Beyond for the rest of our lives.

SUGGS (speaking in 1987): We could’ve changed the name when Mike left but, not being horrible to Mark and Woody, Mike was more Madness than they were, so it seems more logical we should have changed the name then. Actually, someone said that we’re called The Madness because of legal problems, but there’s no legal problem at all. We always wanted to be The Madness. I can remember it started when people in France would go ‘Le Madness!’ It sounds good, it sounds… tangible. And we now think it would be really good from a historical point of view if the change was noted: A new start.

1988

EARLY 1988: With a new name finally chosen, The Madness begin recording their upcoming album.

CHRIS: We worked all the songs out at Liquidator, upstairs on the top floor and said, ‘We’re gonna produce it ourselves, we’re recording in our own studios, it’ll be really cheap.’ Then we ran into difficulties. It was like, ‘I want so-and-so to mix it’, and we spent a fortune in the studio because the engineer had a week mixing it at about a grand a day. So in the end we spent a fortune.

BEDDERS: The Madness lost a hell of a lot of money because the album cost a hell of a lot to make. They spent ages doing it.

CHRIS: We thought ‘We’ve got to get Jerry Dammers down, cos he’s a right laugh.’ So we got him in for a couple of tracks, plus Earl Falconer from UB40 did bass on three numbers too. It was good being able to ask people we really liked, so we had Elvis Costello, Steve Nieve and Seamus Beaghan.

SUGGS: We did it in patches – a month recording, a month fiddling around in a room. Then a month fiddling round, a month fiddling round and a month fiddling round. We didn’t really know what we were doing, so we learned a lot and made a hell of a lot of mistakes. We did try to be different, but ultimately we were the same people.

CARL: Some songs we tried not to make like Madness things, but most of them evolved in the studio rather than rehearsing them with a band in a room, trying to get grooves going. You could call it self-indulgence. We were interested in setting a groove that moved us, that wasn’t a written idea. We’d been more formalised in our recording and succumbed to outside influences before, but this time we didn’t have Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, so we relaxed a bit.

LEE: Clive and Alan were too expensive and becoming rather complacent – and I told them that. If we’d done it with them it would have come out like any other Madness album.

SUGGS (speaking in 1988): It’s different to our normal way of working. Certain things had been ingrained in us over the years, like writing songs and filling up all the space with melody, and those were the things we weren’t trying to do on this album.

CHRIS (speaking in 1988): Suggs and myself programmed all the drum machines. But it’s sort of done me out of a job really, because I used to write the tunes and they’d write the lyrics, but now they’re writing their own tunes and their own lyrics, so I’m redundant

SUGGS (speaking in 1988): The album is a reaction to not having a bass player and a drummer, thinking we’ll do what we want. And having done that, it’s like, ‘Let’s rock out, get a band together.’ It’s all reactions.

CHRIS (speaking in 1988): I sound like the old father figure but I’m really pleased at the way that Carl and Suggs have developed. I mean when we started Suggs couldn’t play anything and now he can play the piano.

SUGGS (speaking in 1988): As a new group, we’ll just be ourselves. Definite plans are that we won’t do interviews and we’ll just do things on a really low level and if they do become successful then we’ll have done really well and, if they don’t, it doesn’t matter because we haven’t spent fuckin’ £650million making albums. It’s doing it for the reasons you wanted to do it for originally, instead of doing it for the reasons people tell you you should do it. So, to make a few quid, and just enjoy it really.

CARL (speaking in 1988): What we’re thinking is that we should promote this album, then maybe get a band together and work as a band doing it the old way for the next batch of material. We do have the intention of playing all the new stuff when we go out live. There’s a lot of songs that we’d like to play at some point, but it has to be the right time.

JEREMY LASCELLES: We had some pretty serious, intelligent thinking artists here, particularly Carl who, in that period, really emerged as a driving, creative force. He was coming up with the most songs and some challenging, different concepts. He had the creative vision and determination to move away from what everyone remembered and loved Madness for. The Nutty Boy good-time band was the cause of their success but also the shackles around their ankles for most of their career. That period was when they were trying to be taken more seriously as thinking songwriters.

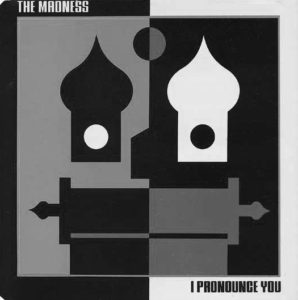

FEBRUARY 25: I Pronounce You/Patience is released

Read more

Co-written by Lee and Carl, the first single by The Madness (VS 1054) fails to set the charts on fire, stalling at No44. One review in the NME sneers: ‘One’s immediate reaction is that they must need to pay the mortgage.’

CHRIS: This one was all about arranged marriages. Lee wrote the lyrics and Carl wrote the music on an acoustic guitar.

CARL: I’d written quite a lot of songs for the album and I felt a bit bad, so I gave this to Lee to write the lyrics and thought he did a brilliant job.

LEE: I offered it up after hearing how Indian parents would marry off their daughters to ‘well-to-do’ men that they’d not even met prior, often living thousands of miles away. Bit like our Charles I suppose! The melody had been swimming around in my head for a long time and, to my surprise, it got worked on and turned out exactly as I’d heard it in my head.

CARL: One of my oldest friends, Ronnie West, had showed me these three chords on the guitar and I loved them. I put a few more chords around them and came up with the song.

CHRIS: The way Carl played it was quite unusual – I tried to copy it but in the end I persuaded him to play acoustic guitar on it as well as me. It was a really good song, with nice flute from Thommo, and I played a bit of sitar on the same electric sitar thing I’d used on Night Boat to Cairo years before – it wasn’t a proper Ravi Shankar-type thing at all.

CARL: I loved the tabla on the track and was pleased with the lyrics that Lee wrote. I also gave Ronnie a credit.

CHRIS: For the video, Virgin originally wanted us to work with some director they liked and showed us a video he’d done, which was the worst thing I’d ever seen; it had someone dressed as the Hunchback of Notre Dame swinging around. It was so bad I walked out of the screening – that was what our relationship with Virgin was like at that point. Instead, we managed to get a film crew together with the help of Carl’s mate Ronnie and made the video ourselves.

CARL: The video was shot in the St George’s Theatre. I was wearing eyeliner, but don’t tell anyone.

CHRIS: We got John Hasler in on drums, even though he didn’t play on the record, and Ronnie’s partner, Alex, played the bride in a wedding dress. We tried to be serious, but Lee was this kind of little imp with a Mohican haircut and we dyed his face red and things like that. We are what we are really. The other things was, we all decided to wear Prince of Wales check suits and white turtle neck sweaters. The people from Virgin said: ‘Wow! Who was the stylist?’ Ha-ha, us mate.

LEE: I was quite surprised that it was chosen as the first single and it duly bombed in the first week. I blame the artwork and the promo video – we’d got all too serious, we were touching 30, a face in the electro pop sound.

MARCH 11: Appear on Friday Night Live

Read more

In their only TV appearance, The Madness playback new single I Pronounce You and album track Beat The Bride on the popular comedy show. John Hasler is again on drums.

watch the performance

SUGGS (speaking in 1988): It’s a really definable thing – you come back and people feel sorry for you. But Boy George was flavour of the month, and he isn’t any more. We were flavour of the month in 1979 – flavour of the week in fact – and we survived for a few years on that. It’s difficult not to be cynical when you’ve been around for so long. You see people grinning and trying desperately hard to be jolly, and you know what they’re really feeling. The music’s staying the same, but the faces are changing faster – or maybe I’m just getting older. I don’t worry about surviving though; we’ll manage whatever happens. Whether we’ll be successful as we were is another matter and one we’re not considering; hopefully we’ll always be there lurking in the background. If we do end up completely and utterly potless, then I personally will have to consider what I’m going to do, because I’ve got a family to look after.

MAY 3: The Madness album is released

Read more

The new outfit’s self-titled album (CD/V2507) also fails to trouble the record-buying public and eventually only reaches No65.

TRACK-BY-TRACK: Click on song title

1. Nail Down The Days

CARL: This one was a bit about being London Irish. That’s what it’s all about, in a way, y’know: “On these great shores I was born / An immigrant to this city / I walked under the steel.”

2. What's That

CARL: This was a very substandard effort to emulate Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues – that kind of feel. And again, it was completely all about where my head was at I’m sure.

CHRIS: We got in a real drummer, Simon Phillips, and recorded his part at our own studio. We went to see him, but we couldn’t see him! He was in this little drum room and he said, ‘I’m going to get the brushes.’ And I thought, ‘What – you’re going to paint the room?’ But he meant drum brushes. He was a fantastic drummer and recorded the part in no time.

3. I Pronounce You

MIKE: I really like this song, I must say. It was very under-estimated.

CARL: I was really pleased because when we recorded it in the studio, I played it all the way through without any muck-ups, which was unusual for me.

MIKE: It’s a good one – but all the stuff they did sounded just as good, with me or without me.

4. Oh

CHRIS: With this one, Suggs and Carl were writing songs and being quite quirky and wanted to do a song that went, ‘Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah’ all the way through. The trouble was, we were kind of on our own and there wasn’t anyone saying, ‘Well, that’s a bit…’. I don’t think Clive Langer was around at all, he was probably off doing somebody successful like Dexys. The song turned out quite well in the end though.

CARL: It makes me think of Kenneth Williams: ‘Ooooooh! Oh no! Matron, no!’

5. In Wonder

SUGGS: I was talking about communication, how often you talk and people don’t really listen. The first lines are, ‘Don’t talk to me in circles, tell me something I understand’, and, ‘There’s so much things to say’ just popped into my mind; there’s so many things to talk about, and you end up talking cack most of the time. I was too shy to put the ‘right now’ in.

CHRIS: I really liked this one and remember playing something called the Synth Axe on it. It was a disgusting-looking instrument that had strings but you connected it to a synthesizer. In a way we could do what we wanted which can be a good thing. Or not. I’d say it is.

6. Song In Red

CHRIS: This one was a very personal song to Carl.

CARL: It was one of my efforts that really sounded good on just an acoustic guitar. Plus it was from the heart and really meant something to me. While I’d seen heart attacks and strokes in my family, I’d never identified a body, then I went and identified my cousin’s body with his oldest brother. That was the first time I’d seen someone dead and I understood, at that point, the transitory nature of life. The Inspirational Choir of the Pentecostal First Born Church of the Living God, who’d guested on Wings of a Dove, actually sang at his funeral at St Patrick’s in Soho Square. It was a beautiful moment that I’ll always remember.

7. Nightmare Nightmare

CHRIS: I was really into this one, along with Beat The Bride. We’d done Nightmare… when Mark and Woody were here, before we split up, but it didn’t sound like this at all and got totally changed. Back then it was called I Remember The Day. In those last band rehearsals, it was one of those African-type things – y’know, sort of bubbly – and I really didn’t like it, so I worked the chords out and did a demo at home, making it more like a reggae song. Suggs wrote some new lyrics and it came out really different. I got quite involved and actually played the piano solo on it.

8. Thunder & Lightning

CHRIS: This is the only one I actually wrote. It’s a Motown-style song and we got Bruce Thomas, Elvis Costello’s bassist, to play on it. He’s great – he did a great kind of Carol Kaye-type bassline.

9. Beat The Bride

LEE: This one came from a real-life event of a family member who was being imprisoned for long periods by her overpowering partner. It all worked out in the end after a bungled Post Office robbery involving her captor. What goes around eh? The captor captured.

CHRIS: It had a sort of similar reggae feel to Nightmare, Nightmare. We used a Linn Drum and you could get the snare, turn this knob and detune it and they literally recorded it while I was twiddling this thing. It’s another Thommo tune all about domestic abuse and that detuned snare was supposed to be the sound of someone being hit.

SUGGS: Carl had a really basic reggae riff that suggested a lot of melody. First Earl Faulkner put a completely different bass line on it. Then Jerry Dammers came into do keyboards and started saying, ‘I hear it like a soca (soul/calypso) song’, and put a completely different hi-hat pattern down. Then he wanted steel drums – it was going so differently, and the off-beat almost disappeared. We had five tracks of what Jerry had done which were completely different to what we had in mind – steel drums, hi-hat, percussion – and he really wanted to come back and put some more brass on it to make it more Barbadian than Jamaican.

10. Gabriel's Horn

CHRIS: This was a kind of mega flippin’ everything-chucked-in song. Again, we’d worked on it before Madness split, so brought it along. It’s another Carl song and it’s a good one. I did quite a lot of loud guitar stuff on it.

CARL: I remember Tears For Fears were recording in the same studio complex as us and heard this one and said, ‘Is this a new direction?’ I thought, ‘Ooh, great!’ It was inspired by Talk Talk’s Life’s What You Make It and the bassline for The Selecter by The Selecter. I had an old cheap piano at home and came up with the bass line, then a few chords. I recall feeling pretty chuffed with myself because I really had to stretch the little finger and thumb to play it, although I didn’t quite match the minimalism of Life’s What You Make It, with its great piano part, vocal and chorus. The song got a bit busy. It has a good energy, but again, it suffered from the absence of Clive. He had a great ability to see the whole song and knew where to improve its dynamics. An old friend of mine was saying recently, ‘You know, a middle eight is essentially what the song is about.’ I’ve never approached a song like a songwriter. When songwriters tell you about how they construct middle eights etc, it’s quite amazing y’know? I had The Rudiments and Theory of Music for years but I never read the fucking thing. Probably should have done, but anyway. Never did figure out what a triad is. Anyway, lyrically this song is again a sort of window to where I was, psychologically; Catholic guilt rearing its indoctrinated head.

CHRIS: We purposely made it very long, which was something we wouldn’t have done before. That doesn’t sound very interesting, does it? ‘It’s very loooooong.’

JEREMY LASCELLES: It was really experimental and avant garde, quite long and out there, groundbreaking, and I was proud of whatever involvement I had with that track.

11. 11th Hour

12. Be Good Boy

LEE: This one was about teaching your siblings right from wrong, good manners, decency and respect etc. Most parents don’t want their heirs to go through the pitfalls they had, so it’s about having pride, dignity, trying to do your best wherever and whatever it takes. Not letting those that care down. Ideal stuff.

13. Flashings

12. 4BF

CHRIS: Lee wrote this as a tribute to Bryan Ferry . The link is that Roxy Music did a song called 2HB (to Humphrey Bogart -– this is also a type of pencil). So I suggested 4BF as a title for Lee’s song (4BF = for Bryan Ferry – geddit?)

LEE: Mr Ferry left Roxy Music without informing the band; they just happened to read about it. I can remember thinking about Mike’s departure when tapping the tune out, although Mr Barson was more honourable. It was good to see this and Be Goood Boy make it onto the CD as bonus tracks and also released as B-sides on the singles. The live version of 4BF rocks!

ALBUM REVIEW

Read more

Suggs, Chas, Chris Foreman and Lee Thompson have left the fairground behind but lost none of their distinctive character, and echoes of earlier days remain – notably on the ska-based Beat The Bride and Nightmare, Nightmare. But, producing themselves for the first time, this album reveals a fresh approach from an agile four-piece willing to experiment with different sounds and song structures, while the loss of the old rhythm section has stimulated the growth of a new percussive richness through some adept drum machine programming and the employment of a pool of bass playing talent. If Suggs’ distinctive vocals can still have fun with picture-story cameos of everyday life on a song like the chirpy single I Pronounce You, the six-and-a-half minutes of Gabriel’s Horn showcase a fascinatingly different concoction of hard-edged guitar, sparse melody and dramatic rhythms and lyrics. Not as instantly accessible as much of The Madness’s early output, this collection is still a much more rewarding evolution than that last LP. And if better than last time doesn’t manage to equal best of all time for the new four-piece, it’s not so surprising. For while the departure of Dan Woodgate and Mark Bedford has allowed The Madness to refocus their creative energy, it was always the brilliant pop talent of the other ex-member Mike Barson that was central to the original musical equation. All the same, songs from the new LP like the superbly enigmatic In Wonder and the excellent Be Good Boy – one of four extra tracks on the CD – reveal how much better a collection it still is than we might reasonably have expected.

Rating: 3/4,

Q

LEE: It was an album I didn’t put that much into when it came to arrangements and production. There were some great songs and good arrangements on it, but ultimately it was very synthetic. Steve Nieve was phenomenal on keys, but it would have been so much better with the involvement of Mike, Woody and Bedders.

JEREMY LASCELLES: I think it was pretty damn good but overlooked at the time because it wasn’t what people wanted.

BEDDERS: In the end, it wasn’t a bad record…

WOODY: …but it didn’t have the magic. They had ideas that they could come up with something fresh and new without the distinctive bass and drum sound that Mark and I gave the band. But it just didn’t work.

CARL (speaking in 1988): I must admit, I find it really hard to say, ‘Brilliant, Brilliant’. It’s a start – maybe we’ll do better next time.

CHRIS (speaking in 1988): Some of it is very recognisably us and some of it isn’t. Carl has done a lot of singing. He’s been doing a lot of writing as well; he’s written well over half the album, which is good because he’s always got loads of ideas for songs and it’s good to get them out of him.

LEE: I think Suggs should have taken lead vocal on all the tracks. His vox sound and delivery on Nightmare, Nightmare is reminiscent of our early albums – that cheeky I-don’t-give-a-damn attitude.

The album’s distinctive artwork is done by graphic artists Rian Hughes and Dave Gibbons, who had drawn for 2000AD and the cult graphic novel Watchmen.

DAVE GIBBONS: I got a phone call from Chris, and I’d always been a great fan of Madness. He thought that something like these symbolic faces I’d put into Watchmen could be part of the design of their album. I met up with Chris in Caledonian Road at their offices. Suggs was there. They talked about what they wanted – toxic warning symbols for hazardous chemicals or fire risks. Chris was quite taciturn but with a clear idea of what he wanted. Suggs struck me as friendly, just as I’d seen him on the TV. They were very open to ideas. They were completely un-rock star like, just a crowd of blokes. I did loads of sketches and I came up with this idea of a square symbol, which was the format of an album or single sleeve that incorporated a full-face view and a profile view as well. They liked my vision. It was quite challenging but, creatively speaking, I always like a restriction – the fact they all had to be square, with representations of some kind of face, and also needed to tie in with the theme of each song, with elements like lightning bolts for eyebrows. For I Pronounce You I did these Indian or Asian style minarets as part of the face. I then went over to Virgin Records with my portfolio. Before the meeting, they took me into the stock room and said, ‘Have whatever you want!’ They’d already warned me to bring a swag bag which I stuffed with CDs. It was generous of them to get Virgin to provide me with all this music! They seemed to know the woman in the stock room very well! When we walked into the art director’s office, I remember Suggs saying, ‘This is Dave, he’s a new member of the band.’ I felt like one of the boys! Although I hardly knew them, there was a sense of camaraderie and I was now in the team. This guy wasn’t very receptive to the whole idea but I stood my corner and they backed me up and we got the go-ahead. They were absolutely supportive and weren’t going to be pushed around by the record company. I then enlisted the help of a friend of mine, Rian Hughes, because I knew this artwork had to have a lot of typographical elements, pin sharp. Rian’s a wonderful typographer who helped me with the technical end. He was able to complete the mechanicals. We also played around with different colours – like warning symbols, you get bright red or yellow. I remember being quite happy with the fee we got.

MAY 16: The Madness release their second single, What's That/Be Good Boy

Read more

The second single (VS 1078) from the album doesn’t even crack the Top 75, peaking at number 92 before dropping to 98 in its second and final week in the charts. The Madness decide to disband.

CHRIS: After I Pronounce You had done fairly well, we were getting ready to do another, but Virgin pulled the plug. They didn’t want to do a video, which was a massive insult. We were going to write them a letter but there was a bit of bottling out, and we then had a twilight period. We just thought, ‘We’ll bounce back and do another album, that’s what they like.’ But instead they said, ‘Unless you play us some new songs within a month we’re not going to pick up your option’ which meant the sack; we would be off the label. This was fine by me, but it caused a few arguments.

SUGGS: It was very painful. Virgin asked us do these demos and we thought, ‘Demos? At this point in our career do we really have to prove we’re any good?’

CHRIS: We started working on some new songs, but we were sort of arguing. Suggs and me wanted to use technology to its fullest, Carl wanted a live band and Lee had gone skiing. Time went by and Suggs announced his decision to throw in the towel. He just said, ‘Look, I’ve had enough. I want to go and try and earn some money.’

SUGGS: I don’t know who started it but I think I might have said, ‘Let’s just knock it on the head.’

CARL: We always said it was doomed from the off. There were some good songs, but it was time to take a break.

SUGGS: It was a mistake and we shouldn’t have done it. It was a very tragic thing that I’m not proud of at all. At the time you think, ‘This all seems perfectly reasonable.’ But it wasn’t – it was the last nail in the coffin.

JEREMY LASCELLES: The music industry is cyclical, and they’d come to the end of a prolonged period where they’d ridden the wave of success and now the stars were not aligned for them. It’s not as if people suddenly went, ‘Oh my God, you suck!’ They just didn’t need any more records and didn’t want them to be the mature, thinking, thoughtful artists they were becoming. I don’t know if calling them anything different, as opposed to The Madness or even just sticking with Madness, would have made any difference. They didn’t feel like a complete, united, happy camp so it wasn’t a huge surprise. Plus, we quite possibly didn’t do a very good job at re-positioning them in an overall marketing sense. It was a little confused.

SUGGS: I remember walking out of the office and down the Caledonian Road and not really knowing what I was, or where I was going. Madness had given me a sense of belonging that I never knew as a kid and for ten years it had been like an intense marriage. Then suddenly it ended and I wasn’t qualified for anything else. The band broke up, I broke down and I lost my point of reference. I was flailing, not knowing what to do, where I was going, what the future held; it was strange and scary. Unless you’ve suffered a breakdown you don’t realise the intensity of something like that. In my head I thought, ‘What the fuck am I going to do? Where do I go now?’ I felt I was staring into an ever-narrowing tunnel and floating in the silence of space. I was terrified that Anne, the kids and I wouldn’t make it as a family and was really paranoid about who loved me and who didn’t and all this other weird shit. It didn’t help that I’d started taking ecstasy too; everyone was doing it, and it just seemed like a bit of fun. But then suddenly you realise that actually you’ve become all the things you didn’t want to become. Eventually I was getting so freaked out that I went to see this therapist. The first thing he said was, ‘Stop taking ecstasy.’ He told me I was getting paranoid because I didn’t know what I was going to do next and was pushing away the people I loved because I was testing them all the time. He said to me: ‘I don’t think we need any grand theories Mr McPherson. You’ve come out of a very intense situation and you’re scared’. And that’s exactly what it was. He was brilliant. He could have given me a lot of fancy theories and told me come back daily for the next 65 years – what I told him set his pencil on fire – but instead he told me I might be better off just accepting myself for who I am. Having never known any security, he said I would always feel insecure, but the thing to do was accept that and just get on with life. It was tough because I hadn’t ever been a musician in my own right, I had been the singer of Madness, so to actually go and think what you’re going to do on your own, was a very strange concept. It was bizarre. I was having to reconstruct who I was again if I wasn’t going to be a pop star. I had left the comfort zone of the band and I was on my own again trying to work out who I was. So it was scary.

CARL: When you come out of a relationship with a certain amount of people, it’s like a marriage. It’s really intense, you know each other inside out, you live in each others’ pockets. I thought about forming a new band, so I did a few things, working with a couple of programmers and getting a band together, but I found it nowhere as satisfying as my experience with my partners in Madness. Without the magical ingredient I felt it wasn’t worth pursuing, so I stopped all of it.

SUGGS: Because Madness was an extremely insular thing, we didn’t socialise with other bands. So I wandered around in a daze for a while, lost in the notion that I was just a member of Madness. I wasn’t snapped up by Whitesnake or Iron Maiden, and I didn’t really know any musicians, so I spent a long time doing whatever came along. I’m not a very motivated person and tended to wait for the phone to ring. Plus I had no aspirations to be a singer as I always felt I was the weakest link in the group anyway. So I was quite relieved just to struggle along in the mud of anonymity.

CARL: I missed having fun, writing songs and playing, but I felt alienated and insecure and was unsure of what course to take. I examined returning to my previous career in petrochemicals but I’d changed, and even though the money was good, it was no longer an option. So because I’d just had my first child, I ended up staying at home for the next three years until the money ran out.

LEE: Having some time off, I kept up my diet of live music by roadie-ing for saxophonist Damian Hand, driving him around for gigs with Howlin’ Wilf and the Veejays because he didn’t have a licence.

SUGGS: It was a weird time; the transition from boy to man. You’ve to remember I was still only 24 or 25 so I spent a long time reflecting on what the fuck had gone on.

JUNE: Lee plays a few dates with the reformed Deaf School, with one Liverpool gig released as a live album, 2nd Coming.

LATE 1988: Suggs tries stand-up comedy at The Mean Fiddler in Harlesden

SUGGS: A friend of mine was organising some stand-up comedy in a pub and asked me to be the compere for a few weeks. He offered me a few quid and said, ‘You’ve only got 15 minutes to fill in the middle. It’s fine.’ I thought, ‘Why not?’ It was at the time when people were saying comedy was going to be the new rock ‘n’ roll and all that, plus I’d done a bit of chat between songs all my career, so how hard could it be? It seemed like a brilliant move – out of Madness and into the new rock ‘n’ roll. But unfortunately, it’s that old story of the fella in the pub who can tell a few jokes and thinks they can do stand-up, but they can’t. I was absolutely useless. I thought I’d be an improvisational comic and just make it up as I went along, but it was so hard; minutes turned into hours. I died every single fucking time. Stood there speechless in front of 20 people who’d come in for the late licence after all the other pubs shut. The promoter obviously put me on thinking I’d be able to draw some kind of crowd but it was hopeless. Luckily, I can’t remember much about it cos I used to get so hideously drunk before I went on. It was very difficult and not something I’m ever gonna try again.

1989

APRIL: It Must Be Love features in the film The Tall Guy, with Suggs appearing briefly in a cameo role.

SUGGS: I didn’t feel like I was a professional musician or singer. I was just a member of Madness: ‘Didn’t you used to be Suggs?’ You’d get that a lot. People would tell me I could sing but I never used to believe it, so it seemed a bit of a fake to do something outside of Madness. I couldn’t see myself in anything other than the band and decided I hated the whole business, and anyway there was certainly no one knocking on the door saying, ‘Suggs! Suggs! You were one of the brightest pop hopes of the Eighties!’

MAY: Suggs appears on Club X

Read more

Suggs appears on Channel 4’s late-night arts show singing a spooky atmospheric number called Make Me Scream, accompanied by a one-woman performance art display.

watch the video

LEE: I remember it was around this time that I’d done 100 mushrooms, really raking it to the edge…wooh! I started off in Barnet at midday and suddenly it was three in the morning and I was hop-scotching on the North Circular road. Then I got convinced that I’d died so I took all my clothes off, apart from my underpants and one sock. I was thinking, ‘The only way to get out of this is to chop my own head off’. I hitched a ride on a milkfloat. The milkman was local and said, ‘I know you – you’re that fat cunt out of Bad Manners’.

Lee and Chris begin working together on new material

CHRIS: After Suggs threw in the towel, Lee and myself picked it up and started writing some songs; it was a really good laugh. We recorded some tracks, then went round the record companies and got spun a right load of old fanny, like: ‘You sure Lee can be the frontman?’ They used to say stupid things like, ‘You need to have a package’ – which meant me and Lee with blond hair and leather jackets.

LEE: We had pukka songs, but they wanted to know what we were going to call ourselves and whether we were going to play live. We thought the music was the first step and everything else would come naturally.

CHRIS: It was insulting to me and Lee. I was thinking, ‘Haven’t you seen any of our videos? You know we can deliver the goods.’ Then we met Link and they said yes and gave us the opportunity to go in the studio.

SEAN FLOWERDEW (The Loafers keyboard player): I’d run a little label, Staccato, which went through Link Records. I said, ‘I can set you up a deal.’ We had a meeting with Mark Brennan and Laurie Pryor from Link, who came down to meet Lee and Chris at Liquidator, which was still functioning as a studio. They’d written the majority of an album and being a big fan, I couldn’t believe that no one cared. The Madness had killed it.

LEE: We played them some right dodgy old tapes which we’d recorded in the kitchen. It was rough old stuff but they gave us the opportunity to up the money to go in the studio. Chris came up with some blinding old tunes, we done a bit of sampling here and there from old reggae songs and [Link] were over the moon.

CHRIS: We went in and did all the backing tracks in about two days.

LEE: It meant we recorded the whole thing in half the time and at half the price of One Step Beyond – it only cost £5,500. The good thing was there was no pressure. It also meant I could let loose with my verbal, lyrical energy.

CHRIS: I wrote everything on keyboards and a few of the songs I didn’t even work out beforehand; I just worked it out on the spot. I was giving Lee the tunes and he was squeezing the lyrics into them, which was quite a fresh way of working. By using machines, we could do everything at home more or less exactly as it would be in a studio except it’s on eight-track instead of 24. You could change the key of things. If Lee wanted something shuffled around, it’s quite easy. It’s what they call these days ‘pre-production’! Within about two days, we’d done all the backing tracks – the drums, bass, keyboards, just the real structure of the songs. We were able to record it easily within ten days.

LEE: It was recorded arse about face really. Chris, me and engineer Kevin Petre went in to Liquidator Studios and used the tools that were around at the time, ie Samples 808 drum machine Roland’s Drumatix/Bassline. It was a great experience and we worked tirelessly on sequencing arrangements.

LAURIE PRYOR (Link Records): The album was put together so differently to how things were ‘supposed to be done’ at the time. It was raw but very real and back-to-basics. We couldn’t believe how good it was – so much better than The Madness album.

LEE: It seemed like a natural move and Chris and I slipped into being in another band seamlessly. We were second to none live and went on to have some fantastic moments.

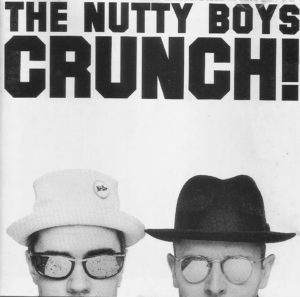

SEAN FLOWERDEW: The only problem was, I don’t think they had really settled on a name. They certainly didn’t want to be called The Nutty Boys.

CHRIS: We were sitting with the boys from Link and they suggested The Nutty Boys, probably as a joke. I said, ‘Yeah!’, but Lee had his head in his hands going, ‘Oh no.’

1990

JANUARY: Suggs starts managing The Farm

Read more

As well as dipping his toe into acting, Suggs branches out into management. After previously producing and singing backing vocals on The Farm’s debut single, Hearts And Minds, which was produced at Liquidator in 1985, he agrees to co-manage the group with Kevin Sampson. The writer is a friend of the fellow Scousers and had produced upcoming film, The Final Frame, in which both they and Suggs appeared.

SUGGS: I’ve always been very fortunate that things have just happened at the right time. And shortly after The Madness imploded, I bumped into The Farm again. I’d helped them out when we started Zarjazz, and we were actually talking about putting them on the label before it folded. They had a good backing with quite a bit of money, and it was just fate they were there at a time when I wasn’t doing very well. They reminded me of Madness. They were a group of friends who were going against the grain. The singer was like me – a character as much as a singer.

PETER HOOTON (singer, The Farm): We’d met at the Oxford Roadshow in 1985 and bonded over a love of beer, music and football, so when we met up again in 1990 we asked him to co-manage and co-produce us.

KEVIN SAMPSON (co-manager): I’d known Pete Hooton for many years and knew him to be a shameless self-publicist. They burst into my office on 16 January 1990 and that afternoon, Suggs joined us in the Crown and Two Chairmen in Dean Street. By six o’clock, Suggs and I had signed for FC Farm. We agreed to manage the band jointly, Terry Farley agreed to provide club mixes, and Produce Records was duly set up in Holmes Building, a chaotic warren of corridors in a Liverpool warehouse.

SUGGS: Me and Kevin did it as a partnership. I produced their first album and gave them advice about people who they could talk to and who could distribute their records. It was a period of discovering what purpose I could serve in the music industry. I’d had success with Madness so knew a hit, but I wasn’t a professional producer. Some of the band were more professional than I was, but we had such a laugh. I remember standing on the mixing desk in my socks, chucking a knife at a poster of Steve McQueen and hitting him right between the eyes. The engineer went, ‘That’s very expensive equipment you’re standing on.’

KEITH MULLEN (The Farm): Suggs was like a mentor to us and quite instrumental in leading us to many a drinking den around Camden.

SUGGS: I think it lasted about a year and a half, until we started on the second album. Then the band started complaining it was difficult and they all thought I was fucking about cos I was in the pub all the time. Little did they know the brain power I was using; the things I was getting into perspective in the boozer while a hugely expensive second album was sliding west. So eventually we parted company.

KEVIN SAMPSON: Suggs wanted a darker album, a heavy, dubby undercurrent with lots of guitars and studio madness. In the end, we all fell out horribly.

SUGGS: I knew the writing was on the wall when they were supporting B.A.D in New York and I kept finding myself on the stage. It was the old cliché of the sweating manager who wants to be on stage, and that’s when I realised that performing was actually what I enjoyed most. That was it – it was like a flash of lightning.

MARCH 15: Suggs appears in Press Gang

Read more

Billed as Graham ‘Suggs’ McPherson, the singer appears in Friends Like These, an episode of the Channel 4 kids’ TV show. He plays Jason Wood, a famously difficult musician who finds himself stuck at a local train station.

APRIL 12: Suggs appears in The Final Frame

Read more

This time billed simply as ‘Suggs’, the would-be actor appears in the Channel 4 film, playing an ageing rock star named East who is murdered on stage at an Animal Rights benefit gig. The film also features The Farm. As part of his new foray into acting and presenting, Suggs comes up with a couple of other ideas for TV programmes. One is Great Scot, which would see him travelling around Scotland in search of his Celtic ancestry. Channel 4 are interested enough to prompt a research trip, which ends up with a boozy weekend in Inverary, but the idea eventually fizzles out.

SUGGS (speaking in 1989): Playing a rock star who’s on his way out… how’s that for irony in my first starring role? The next role I have will no doubt be an actor who used to be a pop star, and who’s useless. Because my character, East, is from Manchester, we did have a small debacle before filming where I tried to speak with a Manchester accent, but it just sounded more humorous than anything else, so they decided not to bother with that. In the end, the compromise was that East’s father was from the north but his mother was from the south, so I’m supposed to have an indiscriminate southern accent.

MAY: The Nutty Boys’ first album, Crunch!, is released.

Review

The latest attempt to revive the nuttiest sound around is a much more satisfactory effort than 1988’s reincarnation as The Madness. They’ve returned to their ska roots to produce an album of thoroughly likeable songs that recaptures the spirit and humour (if not quite the sheer brilliance) that was the essential part of hits such as House Of Fun, Night Boat To Cairo and Baggy Trousers. With Thompson’s rasping sax and vocals mixed well to the fore they skank their merry way through nine original compositions, one of which is a collaboration with Suggs McPherson and a re-run of Fur Elise which receives a similarly syncopated treatment to the wonderful Return Of The Los Palmas 7. As always the tune is the thing, but a closer inspection of the lyrics – which deal with everything from Bill and Ben to drug abuse – are loaded with wit and homespun wisdom.

3 stars, Q

CHRIS: Lee originally wanted it to be released on April 1, but then we found out it was a Sunday.

LEE: We got a real band together and took the songs out to perform live and, as one does, we realised there were so many things we’d like to add and take out.

CHRIS: Magic Carpet was actually written by Suggs in the last throes of The Madness. It was one of the last songs we were writing together so we finished it off after things fell apart.

LEE: I wrote Whistle as a second-class version of England’s Glory by Ian Dury.

CHRIS: Looking back now, I should have rustled up the rest of the band and made it a Madness album but at the time it wasn’t really possible.

SEAN FLOWERDEW: Some of the songs on Crunch! were brilliant; it’s a great album. There was a ska influence although it’s programmed so has that Eighties feel to it.

LAURIE PRYOR (Link Records): We took it to several PR and radio plugging companies who seemed to be turning their noses up at anything to do with Madness. It seemed incredible. One top plugger was more honest and told us bluntly that he could take our money but there was no way any Nutty Boys single would get serious daytime airplay. To be honest, we were stunned.

JUNE: Carl starts work at Go! Discs.

Read more

Disillusioned with being on stage, Carl embarks on a new career direction, looking after the Beautiful South and Paul Weller and trying to control wayward Scousers The La’s.

CARL: After the money ran out, rather than become a minicab driver, I went on a Buddhist retreat in the south of France which cleared my mind of dust and confusion. I returned to London prepared to say those words we all find difficult to speak, ‘Help me.’ I then went to see Dave Balfe, a good friend of mine who’d been in the Teardrop Explodes and ran the Food label. I asked his advice and he suggested I get involved in the industry side of things and do A&R. I wrote 12 letters to 12 record companies. Atlantic records wrote back to me saying they don’t want to insult me with the wages, adding, ‘You are too experienced.’ I wrote back saying, ‘You do insult me – I’m potless!’ So I engaged in a round of interviews and Go! Discs was one of the last I saw. Juliette Wills was there, who used to work with Rick Rogers. So I had a history with her, and Andy McDonald, the owner used to work in the press department for Stiff. So there was a connection with both of them. I thought they were both going to interview me and go, ‘Look how the worm has turned now, you’re looking for a job, and we both worked for you at one point.’ Anyway they turned out to be really cool and Go! Discs at the time was a left wing label that felt really great. A few eyebrows were raised but it was a logical progression – I’d been through it all with Madness and was able to pass on that first-hand experience to the bands I was looking after. I already knew Billy Bragg and Andy had made his name by signing The Housemartins, who were like Madness, plus the label suited me down to the ground as its bias was on good songwriters. I was bought in as a trouble-shooter to help promote the release of The La’s debut album, which I thought was an exceptional piece of work. It was insane working with them – I was literally paying 40 parking tickets each week. My job was mainly keeping Lee Mavers in check and telling Paul Weller to stop doing those stupid videos, but it was great working there. I learned a lot from Lee – who is a genius in a creative sense – as well as Billy, Paul and The Beautiful South.

SEPTEMBER: It's… Madness is released.

Read more

A cash-in Best Of album is released by independent label Pickwick, combining various singles and B-sides. Track listing: House of Fun / Don’t Look Back / Wings of a Dove / The Young and the Old / My Girl / Stepping Into Line / Baggy Trousers / The Business / Embarrassment / One’s Second Thoughtlessness / Grey Day / Memories / It Must Be Love / Deceives the Eye / Driving in My Car / Animal Farm

CARL (speaking in 1990): I don’t know if I’m a good A&R man or not, I won’t know for…God knows when. All I know is from things I’ve done in my own life, I think that attitude always beats technique. It doesn’t matter how good you are at a thing, it’s your attitude with it, so I look for energy and conviction and belief. You don’t really know what’s happening when you’re within it, it’s like when you’re mad, you don’t really know you’re mad. You only know you were mad when you come through it.

NOVEMBER: Suggs stays with David Bowie

SUGGS: Clive Langer had worked with David Bowie on the soundtrack to Absolute Beginners and they became pals. I ended up staying in Bowie’s house with Clive once, in Gstaad, in the Swiss Alps. He invited us to go skiing with him. We turned up with our respective families in Clive’s Range Rover, and there he was, beckoning us up the driveway. ‘It’s David Bowie!’ The garage doors swung open automatically, and Clive drove in. As he did so, there was a huge crunching sound and before we realised the car was too big to fit, we were stuck halfway. Not only that, but all our suitcases had been knocked off the roof rack, leaving our underwear blowing about on Bowie’s drive. Not the coolest start to meeting the coolest man in the world. He was very nice and very restrained but unfortunately he was also going through one of his straight periods. He wasn’t drinking or anything. I was expecting the wild excesses of rock ‘n’ roll as I thought this was what it was all about. But no, just the one bottle of wine and straight to bed. ‘Night boys,’ he’d say at 9pm. ‘You can stay up and watch a film if you want.’ It was rather disappointing.

1991

SUGGS: After The Farm, I did a few things here and there. I worked on the ill-fated BSB satellite station for about six months with Boy George. We both had a show on there, only to discover there were, literally, only about four people watching it. I met one of them in a pub one night – he was this bald guy who couldn’t see or hear.

LEE: I just wanted to get away from anything musical for a while, so I got myself an estate car with a few picks and shovels in it and started a gardening firm called Rosebud, after the Citizen Kane film. I found myself standing in the middle of a garden at midnight, trampling turf down, where I’d sort of under-quoted myself. So that went up the wall, along with the decorating firm that I quickly started up. I was a self-employed painter/decorator called Plumbline. I remember doing one wall and thinking, ‘Those bluebells look a bit sad.’ And I’d hung the wallpaper upside down.

MARCH 4: Kill Uncle is released.

Read more

After Voice of the Beehive and BUtterfield 8, Bedders appears on the new album by Morrissey.

BEDDERS: Working with Morrissey on Kill Uncle was a great experience. Clive Langer was producing it and said, ‘Come along and play electric bass and double bass.’ Mark Nevin from Fairground Attraction basically wrote all the music and then sent it to Morrissey, who wrote the lyrics. He’s really interesting because if you give him a piece of music he writes the lyrics from start to finish to fit the length, without any changes. He doesn’t say, ‘Oh, we’ll have two choruses here’ and so on – he just writes it and that’s it, which is amazing really. He was really professional when he did the vocals, so he just came in and was on it straight away. For my part, it was just a case of coming in and learning all the songs. I really enjoyed it and spoke to Morrissey quite a lot about books and films. One thing he had in common with Madness was that he was a massive fan of Ealing comedies so we talked a lot about those. People often say you have to be careful around him but he was very relaxed and it was a good experience.

OCTOBER: It's… Madness Too is released.

Read more

A second Best Of album is released by Pickwick, featuring the singles and B-sides not included on the previous year’s album. Track listing: The Prince / Madness / One Step Beyond / Mistakes / The Return of the Los Palmas 7 / Night Boat to Cairo / Shut Up / A Town With No Name / Cardiac Arrest / In the City / Our House / Walking with Mr Wheeze / Tomorrow’s (Just Another Day) / Victoria Gardens / The Sun and the Rain / Michael Caine

CHRIS: This compilation, and the one before it, was only available via petrol stations, but they still sold about 30,000 copies each. It showed there was still interest out there.

Lee faces financial difficulties

LEE: I was running very low on cash, so I needed to sell something. So I ended up selling this warehouse pad and moving up to nice leafy High Barnet. That freed up a bit of cash, with which I started a mountain bike shop in Notting Hill Gate. It was a franchise thing, and Debbie ran it. I’d put the house up as collateral, even though I’d only had it for 18 months. Then the bike shop started going down, The Nutty Boys were going down, I got very depressed and the alcohol didn’t help. I was under the covers for a good several months, sleeping all day and wandering the house at night, feeling really sorry for myself. Not a nice place to be. Financially, I was skint and was just preparing myself to settle down with some of the more seasoned pissheads and single men of Camden Town when my wife ordered me to snap out of it and get with the programme. One day she threw the sheets back and said, ‘I’ve got you a job, doing a bit of work for environmental health.’ I said, ‘What department’s that?’ She said, ‘Dustman.’ So I landed up doing that for about six weeks. I turned up at the yard on the first day and they were all chuffing away on the old wacky baccy at seven in the morning. One of the guys I worked with dressed like Rambo, and had a Reliant Robin painted in army colours. Another guy chucked up down an alley and it came up like a pint of lager. It was really grim but it got me out of bed and kept me fit, although the novelty soon wore off.

LATE 1991: Virgin decide to issue another Best Of CD and DVD.

SUGGS: I was still drifting, still not sure of my place in the grand scheme things and what I was supposed to be doing. And then luckily, this lifebelt was thrown to us.

STEVE PRITCHARD (Head of Catalogue, Virgin): It was a catalogue lying fallow and it seemed there’d been enough water under the bridge for it to be worth a look. We did some market research on Madness and it was one of the most positive responses we’d ever seen. Because every generation – mums, dads, kids – thought Madness were their own personal property and loved their hits.

CARL: I was still at Go! and was made aware that Virgin – who owned the rights to all the back catalogue – planned to release a greatest hits, so I became involved.

STEVE PRITCHARD: Our initial contact was with Carl, who was really up for it – his long-term plan was definitely to get them back together again and he took it upon himself to help us make it happen. So I went around with him for a couple of months while he got the band back together. It was Carl’s energy that drove it – he had a vision.

CARL: We decided to get involved so we could monitor what they were doing and make sure it didn’t get tacky.

WOODY: Carl thought it would be a good idea for us all to be involved in the relaunch, so we all came back and did a TV ad to promote it.

CARL (speaking in 1991): We’re not reforming. It may look to some people that we are, but if we were we’d have demos in our pockets and we haven’t. It may look like we’re chasing a buck because we’re down on our luck or whatever but that’s not true of any of us. If we needed money, we could re-form tomorrow and do a tour, but it’s not about that.

CHRIS (speaking in 1991): Naaaaah, there’s not much chance of a reunion. Don’t reckon I’m gonna be doing it. I do love the boys but we did it all ten years ago.

LEE (speaking in 1991): I’m behind Chris. But if the songs are there, then I don’t see why not. But if Chris thinks not, then I’m with him.

CARL (speaking in 1991): All these rumours have been flying around because Suggs and I have been negotiating a new publishing deal. Morrissey did ask us to perform at a special AIDS benefit gig in December, but he was jumping the gun a little.

BEDDERS (speaking in 1991): This has been the first time since we split up that we’ve all been together and in constant touch. What knocked Madness on the head was that we spent so much time together – the routine just got very wearing and tiring. So if we do ever reform, it will have to be really, really good. I wouldn’t do it any other way. I’d even record some stuff and if it was bad, I wouldn’t put it out. I think that’s how everyone feels.

STEVE PRITCHARD: The turning point was when Mike came back from Holland. It really was like the return of the magnificent seven. The gang was complete again – it did feel like a Western. They’d had their sales decline and a critical knocking for the first time and, to start off with, I think they were reluctant to get involved with anything as cheesy as a Best Of Madness.

MIKE (speaking in 1991): The past is gone and I’m looking forward to the future, but I have fond memories of Madness. I think we did pretty well. The music we were making stayed pretty pure. The only regret I have is that some people saw us as this gross cartoon band, which misses the subtlety of what we did.

LEE: By this time, I’d jacked in being a dustman after I got my finger trapped in the machinery and thought, ‘This ain’t worth £100 a week.’ I ended up flyposting for a company in Camden and surrounding areas in the dead of night, which was much safer and much better pay, but involved slightly unsociable hours and a bit of cat-and-mouse with the police. The money from that kept the wolves away from the door, but I had a second charge on the house, so that was definitely going. And then suddenly Madstock beckoned…