1976

From very humble beginnings in NW5, three school friends began to think about more than just graffiti and petty crime.

NOTE: All content in the years 1976-1979 was compiled and written long before the publication of Before We Was We and Growing Out Of It. Additional detail is available in both volumes.

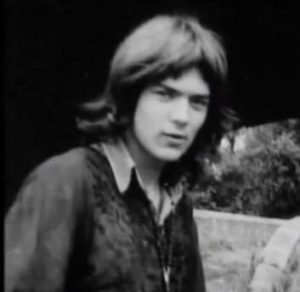

MIKE BARSON: Born April 21 1958, Edinburgh

Read more

The son of two art teachers, Mike grew up in Kentish Town and Muswell Hill. His father left when he was young, so Mike and older brothers Ben and Dan were raised by his mum under straitened circumstances. They each tried to outdo each other on the piano kept in the hall, with their self-taught efforts becoming quite accomplished – Ben playing modern jazz with his hippy mates and Dan with his rock ‘n’ roll band.

MIKE: I used to live in Kentish Town, then my mum sold the house and we moved out to Crouch End. I wasn’t very happy, as all my mates were living in Kentish Town. I felt like I was out in the middle of nowhere. Before that, I went to Brookfield School, between Kentish Town and Highgate. My favourite subject was science because we had a good teacher. Then in 1975 I went to Hornsey Art School because I wanted to become a commercial artist. I used to like advertisements and things like that. I never particularly liked any great works of art, I preferred commercial art and cartoons. But I only completed the first year foundation course and didn’t get in for the next part because I fucked it up a bit. I didn’t really like it there – they were all sort of ponces – so I didn’t go in very frequently. Quite often I’d just go in and spend the whole afternoon playing the piano in the hall. I applied for another three-year course at the London School Of Printing, but I turned up two hours late for the interview and they never let me in. But I wasn’t really that bothered, I was more interested in just practising and trying to get better on the piano. I never bothered to read music or try to learn classical stuff – it never sounded any good, even if you could play it properly; Beethoven and the rest seemed out of tune to me. And you only need to read music if you want to play other people’s tunes. I suppose I was trying to keep up with my brother Ben, who was a brilliant musician. He played all the instruments himself – a bit of a wizard. But there was no rivalry between us; he’d just always been better than me. Ben was into modern jazz and had a five-album box set by Keith Jarrett, which as far as I could hear had one good song on it. He also used to get a lot of old reggae – things like Tighten Up Volume 1. So I used to listen to that and old Tamla Motown – it was the old cliche of my elder brother having the records and me listening to them. I might be a silly old fart, but it was a great time for music back then; I used to listen to Elton John’s Tumbleweed Connection, and I also liked Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Fire In The Hole by Steely Dan had a really nice piano solo on it which I listened to again and again, although I never tried to play it; Steely Dan’s a bit complicated. I did learn Sad Lisa by Cat Stevens on my brother’s piano, playing the record at half speed to try and get it right. I also liked Robert Wyatt and Soft Machine – their album Third is great and Moon in June is a great track. And of course, there was The Beatles. When I was a little nipper, about six or seven, we used to go on our summer holidays to my granny’s in Lewis on the train from Victoria. Me and my brothers used to stick our heads out of the window and sing A Day In The Life at the top of our voices. I can also remember when I was little, we had one of those 1960s record players that would drop singles one by one. I’d get my little Corgi cars out and little aeroplanes and I’d have the record player blaring. It was great! I liked playing on my own, the other kids’ scenarios often seemed a bit lame and half-hearted, but when I was on my own, I could get right into it.

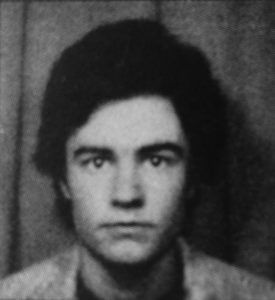

CHRIS FOREMAN: Born August 8 1956, London

Read more

Chris is the son of music hall and folk singer, John Foreman, who had been singing at clubs across Britain since the great folk revival of the 1950s. A former teacher, busker and Punch & Judy man, he was dubbed ‘The Broadsheet King’ for printing and binding countless pamphlets, songsheets and books. The experienced musician had tried to teach a young Chris to play guitar, but he soon got bored. However, at the age of 17, he bought a cheap second-hand guitar and became more enthusiastic when he began to learn chords. He then acquired a Fender Telecaster for £20 with a tax rebate, at the urging of Thompson, so he could join rehearsals in Mike’s bedroom.

CHRIS: I’ve always lived in London. I was born in the University College Hospital and brought up in Kentish Town. My parents split up when I was 11. I lived with my dad and my brother beside the railway bridge on Kentish Town Road off Highgate Road, on the way up to Parliament Hill Fields. It was a funny little terraced house connected to the railway line; when a train went past, our whole row of houses shook, like the house in The Blues Brothers. It was an old railwayman’s house, very basic – we didn’t have a bath or central heating and the toilet was outside. My dad was on the folk singing circuit. He sometimes wore a pearly king outfit and sang funny cockney musical type songs and was known as the Broadsheet King. He’d sing my younger brother Nat and I songs at bedtime which was really nice. He also used to try and teach me guitar when I was a kid, but I was never really interested in things like Bobby Shaftoe. Because my dad was a teacher, he used to get nice long holidays. And because he was very left-wing, we used to get in his van and drive over to places like Yugoslavia and camp. We never had any money – I don’t know why – so we didn’t have a television and used to listen to the radio a lot. Mike and Lee lived nearby and I gradually got to know them; Mike’s mum knew my parents so over the next few years, we would occasionally nod at each other in passing. I must have been about 10. Then around 1971, kids from the Highgate Road in Kentish Town area amalgamated into groups. In my particular group were John Jones, Paul Catlin, Lee, Mike and myself. We used to walk from the Lido up this hill and set fire to all the rubbish bins on the way. We’d get to the top, look down and survey all these glowing rubbish bins, which was quite fun. The park keepers used to chase us in vans at night. I went to grammar school in Islington – Dame Alice Owens. It’s been knocked down since but Alan Parker and Spandau Ballet went there. Best times ever. Oh what fun I had as the song goes but at the time it… actually didn’t seem that bad. One big laugh, but it was a crap school. My music teacher was awful and I never had much interest in the subject. Instead I bunked off and went to Haverstock, Lee’s school. I went in the classroom and the teacher’s going, ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘I’ve come from Birmingham’ So I actually got expelled from Lee’s school! I used to listen to a lot different types of music at school, but Roxy Music were always my favourites. My teenage years were Roxy, Alice Cooper, the Kilburns, Motown, reggae, Hawkwind, Alex Harvey… the lot, really. I feel lucky to have grown up in the 60s and 70s as the music was so good (although there was plenty of mush too). I also loved the Beatles, but that was compulsory really. In fact I later wrote a very Beatles B-side called Please Don’t Go. As my taste in music changed, so did my ‘look’; in ’69 I was a skinhead – brogues, suit, Ben Sherman, Brutus, Jaytex shirts the lot – but by the early 70s, I had the longest hair in the school, even though I still had a Harrington jacket and DMs. Anyway, I wasn’t a great student and only got one O Level – English. I finally left in 1972 when I was 16. Well, I was asked not to come back actually. During the summer holidays, I had seen a gardening job advertised in a newsagents, which I successfully applied for. After the holidays, I eagerly returned to continue my education which was sadly not to be. So I stayed at the gardening firm for about two years. I then worked for the glorious London Borough of Camden as a gardener with Lee. We were both quite interested in music and were always saying we’d start a band. We also used to wear donkey jackets with LBC on the back, and if people asked what it meant, we said London Brick Company (or the more fruity London’s Biggest C**t). Having by now learnt a tremendous amount about gardening, I then applied for a job on the Camden painting and decorating department and got sacked after about six months for turfing someone’s front room and wallpapering their window box. Gardening was great fun – I still go and look at the bits of wasteland we turned into gardens.

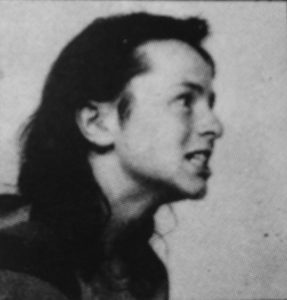

LEE THOMPSON: Born October 5 1957, London

Read more

Lee’s dad, Fred, was a safe-breaker and was often away at Her Majesty’s pleasure. Between 12 and 14, Lee himself was a regular in court, mainly for an ingenious scam on the old grey GPO phone boxes – insert a bit of cardboard and you could walk away with up to a pound. There was also a little light housebreaking and shoplifting of records. Eventually he was sent to a Chafford Approved School for wayward boys. On his release, he began knocking about with Kentish Town neighbours Chris and Mike, with a favoured pastime being jumping freight trains.

LEE: My mum went up to Great Yarmouth to be a waitress post-war in the 1940s, and that’s where she met my old man, Fred. They got married around the time of the Queen’s coronation, and then they had me a few years later. In the 57 years my dad was alive he spent 25 in prison, so Mum didn’t have much control and couldn’t really handle me, so growing up I was a right naughty boy. I was very cheeky and a bit of a Tasmanian devil, all over the place, no concentration span; I’m still the same, but I’ve sort of refined it a bit. I was very disruptive at school – I remember putting a magnet on a tape recorder, which erased all the information, so the teacher, Miss Durham, made me sit in a bin all lesson. But I was never bullied, which was a problem for some kids; I just used to turn up, get marked in and go straight down the arcade. I was meant to be at Burleigh school but I didn’t go much. I wasn’t really that interested and probably spent more time off than in the classroom. I went in for a few exams but I was only really interested in English and Art. I also had a little gardening job and used to like it so much that I’d be off doing it even when I was supposed to be in class. I lived at Gospel Oak originally, then I moved from Highgate Road in Kentish Town to Holly Lodge estate. Everything went downhill when we moved there. At that time, I used to knock around with a chap called Robbie Townsend – God rest his soul – and we used to get into some pretty serious trouble. From about nine or 10 upwards I was very bad and got into burglaries, but never violence – I’ve never committed violence. In my heyday, between the age of 10 and 14, I was in and out of bother and clocked up 13 court appearances. All my mates’ parents thought I was a lout and some wouldn’t let their kids hang out with me because I was such a bad influence.

JOHN FOREMAN (Chris’s dad): Lee was certainly one of the wilder local lads.

LEE: I remember I lost my virginity just down from the police station, in a big metal container which held smashed windscreens. I climbed out half an hour later with a lacerated bottom and knuckles and her arse was like a tramline; ripped to shreds because I was on top.

MIKE: None of the parents really liked Lee; we weren’t allowed to play with him and he wasn’t allowed to come round. The only explanation given was, ‘He looks a bit dodgy.’ I think it was because his dad was a bit of a crook.

LEE: One time I said to my dad, ‘I’ve left the second-floor window open at Haverstock School.’ So he drove me and my cousin down, and we climbed over the fence. Inside there were two or three dozen boxes of musical instruments. So we filled our bags with clarinets and flutes and what have you, and I put the bag round my neck and started climbing back down the lamp-post outside. We dashed back across the playground and climbed back up the wire fence, only now we’re weighted down, so we were wobbling all over the place. My dad was revving the car like it was the Brink’s-Mat robbery or something, shouting, ‘Come on son!’ The whole lot ended up getting sold, but I never saw any of the proceeds. I only did it to get a clarinet, which I tried to play for about six months.

CHRIS: Lee was this sort of enigma. He would come to the end of my road and whistle really loudly; I’d look out the window and see him standing under the lamp-post.

MIKE: I remember he had a sort of sparkle in his eye even then, at that young age. That’s something I remember about him.

PAT BARSON (Mike’s mum): They all played out together. And occasionally they got into trouble together.

MIKE: All the kids hanging around in that neighbourhood were up to no good; there were a lot of broken families and so there was a lot of petty criminality going on, which was difficult not to take part in.

LEE: There was an estate near me at Brookfield Park being knocked down. We’d wait for the removal vans to go, then wallop! Through the window and off with the old meters. That’d get you through a couple of weeks, pair of dogtooth loafers, a jar of Brylcreem. So I was going down that wrong road and it came to a head in October 1971. On my 14th birthday I bunked games, went to Whitton Hospital, bent this locker door open and had this purse away. There was a stupid amount of cash in there – about £200 – so it had to be someone’s savings. It was like, ‘Oooh. Bingo.’ It also worried me as this was big time, so I ended up giving a load of 50 pence pieces to friends down the youth club and buying this girl a patchwork smock, and a dogtooth suit for someone else. Then a few of the mums started to question, ‘Where on earth did you get this from?’ Five days later I was grassed up and taken to the station. I was put on this identification parade, and I was the only one in it! The woman just came in and said, ‘That’s your man.’ I remember sitting there, looking at these bits of paper and saying, ‘Yes, I did that… I remember that… no, I definitely didn’t do that.’ They took six other charges into consideration and gave me a good hiding, which I deserved, and then I was removed from the area. The Holmes Road constabulary in Kentish Town had had enough of me and Robbie so we got split up, just in the nick of time. Bob was sent to one place, and I was put away in a school out of London from November 1971 until January 1973, which was fortunate because it nipped things in the bud in that respect – I was going down a dodgy old path. First of all, I was remanded in Stanford House in Shepherd’s Bush – Mike and Chris came to visit me once and when they left I was in tears; it was gut-wrenching. I then sent to Chafford School, where I was in a dorm with about ten of these right heavy blokes. The lights would go out at 9pm and you’d start to hear the sheets rustling. I ended up having a breakdown there, but funnily enough, the whole experience gave me order and discipline, which I needed – though you never would have guessed.

CHRIS: Lee used to come home at weekends – he’d get out on Fridays and we’d spend the weekend with him and see he got back on the train OK.

LEE: It was at Chafford that I really started listening to music for the first time. Growing up, I’d never had a record player and we never even had a radio at home, I don’t know why. The only TV music you’d get would be Top of the Pops, although stuff like Motown and reggae had jumped out at me, but at Chafford I started listening to stuff properly. Roxy Music’s Andy Mackay was also a big influence and I had pictures of him all over the wall. So I’ve got some fond memories of the place. When my time was up and I was sent back to the smoke I went home and found that my parents had moved to Luton, so I went up to Denyer House in Highgate, where my Uncle Jack was staying. He said, ‘You can kip down here for a couple of days.’ I stayed there Friday, Saturday, Sunday, which turned into Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday… I just knew I never wanted to go back to Chafford, so I started knocking round less and less with Bobby Townsend and more and more with Chris and Mike. It was a fortunate privilege to have met them when I did. They weren’t into the serious things I was and I think if I hadn’t have met them I would’ve gone down the pan. They took me by the hand, pulled me to one side and told me to try music instead of a crowbar – and the rest is history.

MIKE: He ended up being a bit of an influence on us, but I think we were more of an influence on him. He was heading towards a heavyweight life of crime because he was mixing with the wrong kind of people, then he started mixing with us and we got a little bit involved in a lightweight life of crime.

LEE: Rather than getting up to no good and being very bad, we were more into petty shoplifting, and graffiti and jumping freight trains — y’know the usual stuff. There was a train line that went across Highgate Road that had freight trains that went out to wherever, and we used to jump those here, there and everywhere, just to save hanging about at bus stops, sniffing things and getting up to no good. In fact we went to France in Autumn ’74 – me, Mike and a friend called Si Birdsall – and jumped the freight trains over there. We got as far as Toulouse and Dijon. We also went to Paris and got half way up the Eiffel Tower. Getting up was OK, but coming down was very difficult as we happened to find an open door with crates and crates of lager in it. Those were the days.

MIKE: There was always something about railways. They were at the back of everything somehow, round the back of houses where nobody went.

CHRIS: We would jump on and imagine we were hobos, then end up in Highbury. Sometimes we’d open the goods train containers and see what we could find. We found a crate of hot dogs once. We also got a massive outboard motor but we didn’t know what to do with it, so we just chucked it in the bushes.

LEE: On bank holidays, we used to take off on a freight train up to Leamington Spa, mainly northwards. We ended up in Leigh-On-Sea once, near Southend. Jumped out, pitched the tent, woke up to find cows nibbling at the strings.

MIKE: We used to build little camps over the railway, and we’d hide in them and when a freight train would come along, we’d run after it and jump on the back, go over to Willesden or Tottenham on little shoplifting sprees.

LEE: By this time I’d left school and was doing the gardening with Chris which was great – I earned all of £11 a week. But I could never hold down a job full time. I’d work for, say, nine months of the year and have the rest of the time off.

CHRIS: We were delinquent but nothing too bad; I did a lot of shoplifting and a little graffiti. Lee and Mike were more talented in that department.

MIKE: We were all just a bit different from the run-of-the-mill youths in our neighbourhood. That weren’t many other kids who were into music like we were. We were into performing and dressing up and being the centre of attention and leaving our mark – which is why we liked doing the graffiti.

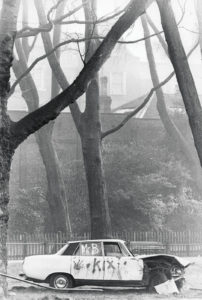

Kix, Mr B, Cat and Columbo

Read more

Using their distinctive signatures of ‘Mr B’ and ‘Kix’, Mike and Lee express their early artistic identity on the walls of North London, along with two pals ‘Cat’ and ‘Columbo’ (Si Birdsall – more of whom later). Lee’s full tag – J4 KIX 681 – stands for ‘just for kicks’ and the house number where he lived. The gang’s notable canvases include the Lido swimming-pool off Hampstead Heath and Highbury & Islington tube station. They also spray their nicknames on George Melly’s garage door, prompting the jazz star to write a newspaper article declaring: “If I ever catch that Mr B, Kix and Columbo, I’m going to kick their arses.” A later book on London graffiti by Melly, Watching The Wold Go By, features a photo of Barso’s work – a car crash scene with a blood-drenched hand hanging from a car window.

LEE: I first remember seeing an ad in the Sunday Times colour supplement around ’73 that had a piece on graffiti carried out in the dead of night on the New York subways and trains. It really inspired me, so to pass a little time, we acquired some aerosol cans and got to work. It was easy to get cans out of Woolworth’s then – silver and black. We used to spray paint old buildings and corrugated iron to keep ourselves out of trouble; it was all very artistic I’m sure but I know we pissed off a lot of council boroughs; certainly Camden.

MIKE: I don’t know why we did it. I suppose it’s like dogs who like to go and pee to mark their territory.

SI BIRDSALL: Mike was very good at drawing and did a good one at Highbury Station, from the Kilburn and the High Roads album. It’s still faintly there.

KERSTIN RODGERS: ‘Kix’ was a common graffiti around Hampstead, Gospel Oak and Camden. I knew his tag before I even met him.

MIKE: Lee was called ‘Kix’ as he was into kicks, y’know – an adrenaline rush. He liked to be naughty and daring, spraying his name on the top of the railway so everyone would say, ‘How the hell did he get up there?’

SI BIRDSALL: I used several names – ‘Columbo’ from the TV series, ‘Sha Na Na’, ‘Sneaking Sally’ from the Robert Palmer album. I think what brought an end to it was we went up to Woolworths in Hampstead and went crazy. We got carrier bags full of spray paint, three or four of us with two carriers each. We hid them in a cemetery, and for a week after we just overdid it – we just got fed up with it.

MIKE: While we were up to all this, Lee would still have to wait around the corner because our mums and dads didn’t want us to hang around with him. Everywhere we went, he would suddenly be nicking something or breaking into something, which was sort of fun. I didn’t like breaking the law really, but when you hung about with Lee it was sort of inevitable because he’d always be up to something.

CHRIS: Even though he was a bit of a criminal, it wasn’t entirely Lee – we were all quite bad. But we didn’t go round mugging people; it was mostly vandalism and a bit of shoplifting, although Barso couldn’t run very fast, so he always got caught. Me and someone else used to steal those patches that you sewed on your jean jackets. But it was mainly albums.

MIKE: We were all into albums and we used to go up to the Co-op in Camden Town. Unlike a lot of shops, they had the records in their sleeves.

LEE: It was the only place where they actually had the wax in the covers, which made it a goldmine for us.

MIKE: You’d put your jacket over your shoulder, look over there and suddenly the record was under your sleeve. And then you’d walk out the door hoping no one was going to grab you.

LEE: We also used to get Levi’s and Ben Sherman shirts – all sorts really.

MIKE: One time we were coming out of Kentish Town station – we’d been down the West End – and there was a police car, and they all sort of knew Lee. And one of them said, ‘Oi, you! Thompson! Come here!’ And we just started running.

LEE: There wasn’t a day went by when you wouldn’t get into trouble; it was just one of those things.

PAT BARSON: Lee had this attitude to other people’s property that it could be his as well. In those days, the bus conductors used to have a purse of money that they’d keep in a little cupboard at the back of the bus. I’m sure that Lee once leapt on the bus, took the bag and leapt off again.

JOHN HASLER (friend): He once asked me, ‘Do you want to come for a drive?’ He got hold of his dad’s car – I’m pretty sure he didn’t have permission – which was this great big red Ford. Off we went for a drive, and he could barely see over the dashboard.

PAT BARSON: He was quite a nice kid but most of the time I wished he wasn’t there. He really worried me because he had this potential for really getting into trouble, and it meant that Mike and Chris got into trouble as well. He wasn’t a very good influence.

CHRIS: I got caught doing something once and my dad had to come to the police station. He bit the bullet and spoke up for me, saying his marriage had broken up, and I felt really bad. So I stopped doing it – especially because by now I was married. Around 1974 I’d met a girl called Susan and we got hitched in 1976 and had a son called Matthew. So I moved away from the usual antics, although Sue and I used to bunk into the Hampstead Classic cinema.

LEE: I had a massive record collection, most of which was pinched from Woolworths and various shops that had the albums sealed in their packaging, which was the norm back then. Cameras were virtually non-existent or were those massive Dalek head-type dome eyesores, that were normally positioned over by more desirable items like electrical goods. I was once hoisting along with Chris, Mike and an old ringleader John Jones. John and myself grabbed a chocolate mousse each, I climbed on JJ’s shoulders and put the mousse cups over the eyes of the Dalek — fun and games in South Kensington via shoplifter’s dream, in Biba. The power cuts of Christmas ’73? (or was it ’74?) must have cost the economy pound notes that winter.

CHRIS: We used to use this shop back in the day called Ben Nevis Clothing, on Royal College Street, NW1. One day, Thommo nicked a Harrington that was hanging on display outside. The owner chased him all the way to Highgate Road but he never caught him. After that Thommo was banned from the shop.

MIKE: We also used to hang out in the Perfect Dry Cleaners in Highgate Road, plotting low-level anti-social behaviour we were too lazy to do.

LEE: We liked it cos it was warm and you had a roof over your head 365 days a year.

MIKE: We used to look out the window and see the freight trains going past, which we used to jump on. You could see the signal, and when it went up, that meant there was a train coming. The train would go over the bridge, we’d run under the tunnel, up the side of the embankment, quickly have a look where it was going and jump on.

CHRIS: We were just mates living near each other in Kentish Town – nothing to do, no real plans.

LEE: We started to get into music like David Bowie and Roxy Music – I actually remember trying to dress up as Bryan Ferry. I once climbed up on the roof of the Rainbow theatre with Si to see Roxy, supported by Leo Sayer. As I’ve pulled myself up to this window, there’s Leo painting his face in the mirror. When we got in, we were up above the band with all these dead pigeons and gunge; when we got down we looked like a couple of kids from Oliver. We were so lucky where we were. We were at the epicentre of it all – Dingwalls, the Tally Ho, the Lord Nelson. It was a stroll away to your nearest live venue, a couple of bus stops away; it was all around us. We used to go and see bands at other places, like the Nashville, the Roundhouse and the Hope & Anchor; it was about 50p to get in. If we couldn’t afford it, we’d bunk it because he doors were a lot easier to get through in those days. That’s how we got in to see people like Gary Glitter. There weren’t many soul or blues or reggae artists around then, so I never got to see the likes of Bob Marley. It that was more when pub rock was big, which I was attracted to, so we went to see live bands and artists such as Ian Dury, the Feelgoods and the like. Many a Saturday evening was spent watching the Kilburns. I also went to see Alex Harvey down the West End somewhere with Mike, Chris, Si and a couple of pals. We walked in and there’s this character on stage with a stocking over his face and a big wall that he smashed through. Just his antics and the visuals really took me.

CHRIS: One time, me and Lee even bunked in to see David Bowie at Earls Court.

LEE: It was when he was promoting Aladdin Sane – it was levitating.

CHRIS: I borrowed some eyeliner off Lee’s cousin Lorraine just to blend in and get past security. We looked quite good actually.

LEE: Chris had a navy blue satin jacket and I had a cream one. On the back it had a Japanese garden. Chris also wore sailor trousers – bell bottoms and navy blue – and I wore white ones. We did take some stick – it was a bit difficult, what with our hair having gold and silver spray in it too.

CHRIS: We used to wear these flares called loon pants, which you could buy for 99p – I’ve still got the photos to prove it. Then Roxy Music came along, so it was sewing bits of leopard fabric on our Levis then back to Dr Martens, which we used to dye. I also had a satin bomber jacket and wore glitter t-shirts, plus we used to ‘get’ stuff from Biba, which was an incredible shop in Kensington. I had some knee-length suede patchwork boots from Ravel and also wore tank tops from Chelsea Girl. We used to modify our clothes, sewing patches on, bleaching jeans, jean jackets and so on. Then I got into the casual soul boy look and had these really baggy soul trousers. We used to get a lot of stuff from second hand shops, mainly suits and trousers. We also used to wear bowling shirts, which we ‘got’ from a shop called Flip in Covent Garden. We liked the American Graffiti look with those high school college jackets that had numbers on. We also dyed our hair red with vegetable dye and Mike dived in the lido and it all came out. Of course, that was when we had hair.

LEE: From going to all these gigs, we liked what we saw and decided to get into it ourselves. So the three of us decided to stop hanging about at bus stops, doing this and doing that, and form a group. I got myself an old sax held together with elastic bands and helped Chrissy Boy get a guitar. There was this semi-acoustic guitar in a shop in Camden and it was something like £28. So I changed the label to £8 – this was in the days before barcodes – and said to Chris, ‘I’ve seen this guitar and it’s right up your pay packet.’ So he came down, looked at the price and thought, ‘Hmmm, must be in the sale.’ So he got himself a guitar for eight quid.

The first rehearsals

Read more

Mike, Chris and Lee start rehearsing at the Barson family home in Crouch End, North London. Playing along to shoplifted Fats Domino and Temptations albums, they rehearse in a guitar/sax/piano formation three times a week. Mike, who’s had a few classical piano lessons and years of self education, teaches Chris to play guitar, while Lee, originally a clarinetest, practises on a stolen sax. Lee’s huge collection of ska, reggae, Motown and Atlantic soul and singles play a major contribution to their early sound. But the varying degrees of talent regularly lead to tension, with Lee often walking out for weeks.

CHRIS: Lee and I used to go round to Mike’s house to play records and muck about, which is where the group idea started. Lee and me then started to learn guitar and sax in Mike’s front room. Mike’s mum was tremendously understanding, though at times we nearly must have driven her potty.

LEE: She was OK with the noise up to a certain time. We used to make a right old racket, what with me playing in the wrong key ‘n all. It must have really upset the neighbours. But at least she knew where we were and she knew that we weren’t getting up to what teenagers get up to.

MIKE: Nobody could really play anything for quite a long time. We just played the records we liked and stuff we’d heard from older brothers – a few ska records, lots of Coasters, Love Potion Number Nine and Poison Ivy.

CHRIS: Lee and Mike nicked an old Fats Domino LP and brought it back so we could play along with that too.

LEE: I’d ended up with the sax after trying pretty much everything else. At school I’d gone through the whole music section of different instruments; flugelhorn, trumpet, trombone – but no saxophone. The clarinet was too difficult, fingering-wise, so I went on to the oboe but that only lasted a few months. The embouchure around the lips and the muscles around there was like I was being given a dead leg; it was impossible. So then I moved back on to the clarinet in 1975 when I was about 18, because that’s all I could find. I had it for about six months but I didn’t like the sound of it; it was too jazzy. I played along with Stranger on the Shore, but there’s only so many times you can play that without getting bored shitless. At the time I was listening to a lot of Andy Mackay and he inspired me to start thinking about taking up sax seriously. He was like a God and I loved his style of playing – not too busy, not too John Coltrane, not too technical either. I wanted a big gold sax like his. I was also listening to The Coasters, Little Richard and a lot of Fats Domino and his contemporaries and that got me going too – it was just the music I was into. All the American R‘n’B I loved had sax on it and suddenly there was a resurgence of all things 50s. At the cinema it was The Lords of Flatbush, Badlands and American Grafitti. Fashion was very 50s again. Flip and the flea market were importing American retro bowling jackets, shirts and trousers at reasonable prices. Sha Na Na, Rocky Sharpe and the Razors (later Darts) and of course Bazooka Joe were playing a genre of music that liked and that featured that breathy, organic saxophone sound. Whenever I went along to see a band, I’d go running down the front into the line of fire as I called it, the Bermuda Triangle – a very tame, glitter-sprinkled Bermuda Triangle – and would always prop myself up in front of sax players like Andy Mackay, Davey Payne and Damian Hand. The sound just made me levitate, so I swapped my clarinet for a battered old Boosey & Hawkes tenor sax down Dingwall’s Market. It was a silver-white broken down old thing but it got past the first audition with Mike and Chris. From then on, I sort of taught myself how to play it, playing along with old Roxy Music albums and a lot of black R‘n’B from the 50s. All I had on my mind was the saxophone and getting to learn it, so I spent a lot of hours in front of the mirror mimicking, if not mastering, a lot of Fats Domino tracks. His music and certainly his saxophonist session men inspired me no end.

CHRIS:Back then, Lee and I definitely didn’t have a clue. Mike was really good on the piano and always seemed to be able to play, right from when I first knew him. But he was lucky – he came from a musical family and had had some musical training. His eldest brother, Ben, was really good too and had played with lots of people. He also had lots of equipment, like guitar amps and a piano, so he just picked it up as he went along. I really only took up the guitar when I got a tax rebate and Lee suggested I buy one. I got a Waltone semi-acoustic – £20, a real cheapo Woolworth’s type thing – and started mucking around with it round at Mike’s. I wasn’t really that interested though; I never took lessons or tried to play the thing except when we were together. I just used to play these notes, one string at a time – I wasn’t very interested in it. It was only when I got the sack as a painter and decorator that I started to play by listening to Dr Feelgood. And then I started playing chords and that was what really started me off. I later lent the guitar to an old school friend in the 80s, but he doesn’t know what happened to it.

LEE: I suppose I first got into a group because I wanted to be like Gary Glitter. I thought it was great the way he came over so positive and full of confidence. He knew his image was outrageous, but he wasn’t pretending he was the second coming. He just acted like someone who was genuinely grateful to have show business as a job. I kinda felt like that. Plus I’d always been in a gang, ever since I got out of nappies.

CHRIS: In the beginning, we were just jerking around in Mike’s bedroom, listening to old reggae and rock’n’roll records and trying to copy them. We tried being serious but it never worked.

LEE: We started practising in school halls, though we’d always end up back at Mike’s mum’s house, and then we all managed to get better instruments. Some friends heard I was starting this little group so approached me with a very hot Selmer Mk.6, fresh out of the shop window. They used to go to a club at Centre Point and one night they came out in the early hours and walked up Hampstead Road towards a shop called the Fender Soundhouse, just up from Warren Street. There were these little Venetian windows, so my friend – Pete Kennedy, God rest his soul – got on his pal’s shoulders, took the little slats out out and climbed inside. He passed out a guitar, then a twin-neck guitar, and the others took them round the corner. He was just about to hand out a saxophone when the others noticed two policemens’ helmets coming from the distance. Pete couldn’t get out, and he couldn’t go anywhere else because the place was lit up like a Christmas tree. So the other two stood on the edge of the pavement, boisterously mucking about to distract the coppers’ attention, and Pete stood stock still like a mannequin with the sax in his mouth. I wasn’t there of course, honest guv. So lo and behold, a saxophone suddenly became ‘available’. My wife was good enough to pay the £100 to purchase it from Postman Pete, which I still owe her. That was the same sax that I played on our first album, One Step Beyond.

DEBBIE (Lee’s wife): I remember buying it from the people who stole it. I can’t remember him expressing that he wanted a saxophone, but he must have done, or I wouldn’t have spent a week’s wages on it.

MIKE: Because me, Lee and Chris all grew up together, we all had quite a lot of similar tastes. We used to listen to Motown a lot, so we used to try and do that in the early days – we did Shoparound, See You Later Alligator, that sort of stuff, all other people’s music. I’d had a few lessons, but most of what I know was self-taught. We learnt different set pieces; rock’n’roll on the left hand and fiddling round on the blues scale on the right hand.

CHRIS: We were just having fun. Mike was pretty good on the piano, Lee couldn’t really play the saxophone, and I had a cheap guitar with an instruction book. Sometimes, those books have dots to show where you’re supposed to put your fingers – but this one had photographs that showed the fingers in position, so it was easier. It took me about a year to get anywhere. Mike nurtured me and Thommo really – he knew where all the chords were: ‘C? Hit that one.’

MIKE: I used to put stickers on the guitar so Chris could play properly. On each one I wrote the names of the notes – C, B, D etc – so he could learn the chords.

LEE: It was a long, tedious process but Mike was a great help. I remember sitting in a pub with him, just going through the basics; the scales, the crotchets and the quavers; F-A-C-E and Every-Good-Boy-Does-Finally and all that.

MIKE: I was teaching them both but it was very, very slow work – literally note-by-note.

CHRIS: I learned to play while I was living at home with my dad, my wife and my newborn son. Our old railway houses were finally being renovated but my dad had refused to move unless they guaranteed him the house he wanted, which was next door to our old one. So all the other houses were now empty and covered in scaffolding and we squatted upstairs in my old house, where I slowly tried to get better.

LEE: It was only when I got that new Selmer that I began to get more serious. Return of Django was one of the first solos I learned because I liked squeaks. Love Of The Common People was another one. And somewhere along the line, I managed to string a few notes together.

TRACY THOMPSON (Lee’s sister): We all used to say, ‘He can’t play. Listen to that – it sounds terrible.’ Mum in particular used to say, ‘You’re blowing that thing and giving me a headache.’

DEBBIE (Lee’s wife): My mum used to stuff tea towels down it if ever he was at our house.

LEE: I had my one and only sax lesson at Highbury School. The geezer who was teaching was a right nosey bugger – a real Shaw Taylor character. He told me to play something in the key of E and I didn’t know what he was on about. Then he noticed the serial number was scratched off the back of the sax. It had been nicked, of course, so I never went back. After that I got meself a couple of books and the old Roxy albums and I’d sit indoors and play for about ten hours a day. Originally I was happy just to poodle along to records by Roxy Music, Fats Domino, The Coasters and people like that.

MIKE: The very first song we ever played all the way through, in my brother’s bedroom, was Carole King’s It’s Too Late Baby, which was a very unorthodox approach – very melodic, very naff. A strange choice, but at least we could play a song. That was the first time we had all our instruments working together and it actually sounded like we were playing the same song.

LEE: We also had a youth club to go to – the Aldenham Youth Club in Kentish Town, just up from the Forum – which had a room downstairs. The sound-proofing was eggboxes, and I sort of locked myself up in the club and had a little blow.

CHRIS: At that time there wasn’t anyone I really emulated but I did like Wilko Johnson, and as he used to play a Fender Telecaster, I eventually got one of those. It cost me about £130. As I got better I was influenced by him, Chuck Berry, Phil Manzanera (Roxy Music), Angus and Malcolm Young (AC/DC), Mick Jones (The Clash), Bo Diddley, Nile Rodgers (Chic), Ernest Ranglin… and that’s just for starters. I went to see AC/DC the first time they came to England, at the Marquee – the proper Marquee, none of your rubbish. Angus was just rolling around the floor and I thought it was great. Back then it was Chuck Berry and Duane Eddy for me. The first record I bought was The Beatles, I Feel Fine, B-side She’s A Woman.

LEE: I’d grown up on a diet of The Coasters and Fats Domino; any band from the 1950s seemed to have a saxophone on it, and I was always attracted to that. So my musical heroes were Fats Domino, The Coasters, Chuck Berry, black American music, ’50s rock ‘n’ roll and ’60s Britpop. Reggae also moved me. When reggae used to come on the radio. I could never understand the lyrics but that off-beat sound ‘umm-che-umm-che’ really stuck out. It really grabbed me by the earholes. Way back in ’67 just when Radio One started, I had a paper round and to keep me company I had a Solid State radio. I think it was about £1 2s 6d or something. It was a bit of a lump — about double the size of a packet of cigarettes, with an earphone. And while I was delivering the papers one morning, Tony Blackburn played Tears Of A Clown by Smokey Robinson. The production and the singing really stood out — it just brought me out in goose pimples. When Israelites, Return of Django and Love of the Common People and all that started then coming through the airwaves, I was really drawn to it too. I remember roller skating to Return Of Django at The Alexandra Palace one Saturday morning. It has special memories of youth, foolish behaviour and happiness. Eventually, I got into reggae so much that I used to travel far and wide just to get records – from Kentish Town I’d have to go several miles to Brixton or Willesden where there was a big black population. They never had that kind of stuff in normal shops, so I remember going over to Willesden because I wanted it NOW! NOW! So I had to get a train across to a shop that I knew specifically did Jamaican music. Then one day I stumbled across this Aladdin’s cave of tat – a real treasure trove down in Upper Street, when it was a proper old pre-gentrified area – and found a load of records on labels like Firefly, Punch, Fab, Blue Beat, Blue Ska and Melodisc. I remember picking up this album with the name ‘Prince Buster’ on and thinking, ‘Ooh, let’s have a listen to this.’ What stuck out was this comical fella that sang comical lyrics to a ska beat, like Ten Commandments of Man, and of course Madness. I’d never even heard of him, even though he’d been going a long while, but I loved his stuff.

MIKE: As well as Motown and reggae, we were influenced by bits of rock ‘n’ roll, Stiff Records, Elvis Costello – everything really. I definitely had a Motown book with all the chords in it, but I was such a lazy bum that I never learnt how to read music, so it took ages.

LEE: The Kinks would prove to be such a big influence on all of us later too. I love a song with quirky lyrics. Lola is about a transvestite and at the time, I thought, ‘Woah, that’s pretty risqué’. I mean, I was a fan of The Kinks anyway, but this really turned it round for me — bit better than The Bay City Rollers! Tommy Cooper was another influence, although I didn’t realise it til later. He was always my favourite comedian. I used to get taken to see him when I was a kid, but I never really got it then, it was later that I realised how brilliant he was, the way he could crack you up with the slightest movement.

Kilburn and the High Roads

Read more

Kilburn and the High Roads were a British Pub rock/rock and roll band formed by Ian Dury in 1970. The band consisted of Dury as lead vocalist and lyricist, pianist Russell Hardy, guitarist Nick Cash (real name Keith Lucas, a member of 999) and bassist Humphrey Ocean. The band released their debut album Handsome in 1975. After the release of their second album, Wotabunch!, in 1977 the band split, with Dury leaving to form the Blockheads.

CHRIS: Lee and I used to go and see bands at the Tally Ho. One time we saw a poster that said, ‘Next week: Kilburn and The High Roads’ so we thought anyone with a name like that must be a laugh and we’d have to go and see them. So the next week there I was in the Tally Ho car park, trying to work out how to bunk in for free, and Ian Dury walked by. I assumed he worked in the pub because he was sort of in a suit and a bow tie, so I said, ‘When’s the band on?’ He gruffly replied, ‘I don’t know mate’. Imagine my surprise when he appeared on stage with this totally nutty band. Lee and I were instantly hooked.

MIKE: From that moment on, the Kilburns became a big influence. We used to go and watch them regularly and see how they performed, how they played certain songs. When you saw them sitting round before the gig, there was a real mystique to them. They were a weird and exotic bunch of characters; some of them didn’t even seem to be musicians. The guy who played the guitar was an English gentleman who didn’t even look like a pop star. He’d stand there looking like a twat but he played great music. They were just a bunch of theatrical eccentrics who had the music hall vibe that we connected with; if you watched just one of them all night, it would be a complete show. We definitely got a lot of inspiration from them and learned a lot about a band of characters where there was always something to look at. There was a lot of cross-fertilisation.

LEE: It was going to see them that made me get a sax – the only thing I’d go for was the sax player Davey Payne. He was so good and so lively on stage. He used to have smoke coming out of his sax, he’d throw things at the audience – he was having fun up there as well as playing. I got a lot of the fun element of the group from watching him – he was certainly a big influence on me.

MIKE: I wouldn’t say that Davey was an influence on Lee. What’s the word? Yeah, he used to copy him a lot. In various ways. No one was doing rock ‘n’ roll back then like Ian Dury and the Kilburns were. They had so much variety and strangeness and mystery. Some of those art school bands were a bit too arty-arty, but Ian’s lot were cool, with real music.

CHRIS: We started following them around – we thought they were brilliant, both visually and musically.

LEE: I’ve always been big on eccentricity and Ian had it in every department. From the moment he walked on stage you were transfixed – he wouldn’t allow you to go to the toilet or bar, not in his time anyway. All that music hall-sounding stuff really attracted me.

IAN DURY (Kilburns singer): We used to have to get changed into our stage gear in the toilets and once I can remember Lee climbing in through the toilet window and seeing us lot with our trousers down.

LEE: I was bunking in as I was too young to get in to the pub, but I caught my trousers and was left hanging there. Suddenly this upside-down face appeared and said, ‘What do you want?’ And this hand unhooked me – SPLASH! – straight into a load of pee. I met Ian again later when I’d come out of Dingwalls with Chris and Mike and he just happened to be there. I ran up behind him and said, ‘Hi Ian, can I have your autograph?’ And he said, ‘No. Fuck off.’ Which I thought was fair enough.

CHRIS: We only realised it later, but seeing Ian and the Kilburns and that whole pub rock thing really helped us.

LEE: It was truly inspiring. Before seeing them, I’d never have dreamed I could go and get a saxophone and play in a pop-rock band. But they looked so normal I just thought, ‘Yeah why not?’

CHRIS: Punk also made us realise that you didn’t have to read music or be that good at playing your instrument. I thought a lot of it was just ripping off the New York Dolls, who Lee and I loved. But it opened things up and made it easier for us to get gigs later on in pubs; you didn’t have to be a brilliant musician any more.

MIKE: Punk music itself meant nothing to me. I agreed with the things that bands like the Sex Pistols were saying, I just didn’t think their music was very good; in fact most of it was pretty shitty. I loved the spirit of rebellion, the kicking over of statues, but I missed the musicianship – I like it when people know what they’re doing. It reminded me of when I was doing my foundation course at Hornsey – the way in which technical skill was frowned upon. The lecturers would be really withering about the students who were good at drawing or painting, which I thought was stupid. I suppose punk was a bit like that. When I heard all those punk things coming out I thought, ‘Well, it can’t be too difficult.’

LEE: Back then, Mike was always saying, ‘Look, if Ian Dury can do it…’ With him, Chris and me, we just seemed to be on the same page with everything, whether it was fashion, music, jumping freight trains or doing graffiti. It helped get us all together in one room and start trying to be a band.